Lone Parent Success Story Not Because of Tough Love

John Richards tells us “tough love” was the right public policy stance for governments to take in the mid 1990s. In his report released today by the C.D.Howe Institute, Reducing Lone Parent Poverty: A Canadian Success Story,Richards tells us that the tightening of access to welfare and the imposition of workfare was the kick-in-the-butt that lone parents needed to move themselves out of poverty. He says: “Large reductions in lone-parent poverty demonstrate that the generous social assistance regimes pre-1995 were a bad investment from the perspective of both the poor and taxpayers.”

Looking at the reduction in poverty rates since 1995, one could only see success stories nomatter what group you look at. That is because poverty rates, however you measure them, reached their highest levels in 1996 for every group except seniors who have seen nothing but declines in poverty rates since such data started being kept, in 1976.  Indeed seniors are the true success story when it comes to poverty reduction.

Richards is right on two points. There was an important reduction of poverty rates for lone parents, and they did work more. It may not be because of public policy. Lone parents worked more primarily because of the extra work effort put into the paid labour force by women, and that is as true among two-parent families as lone-parent families. The fact that more people were working, and working longer hours, is less a function of public policies that smiled upon workfare and the destitution of those turning to public support than the fact that Canada created more jobs in the decade 1997 to 2007 than any other G7 nation. When there are jobs, people take them.

If anything, Richards’ work should be a wake-up call on the limits of this approach to poverty reduction, given the scale of job loss that occurred in the opening six months of this recession, unrivalled by anything in the post-war period.

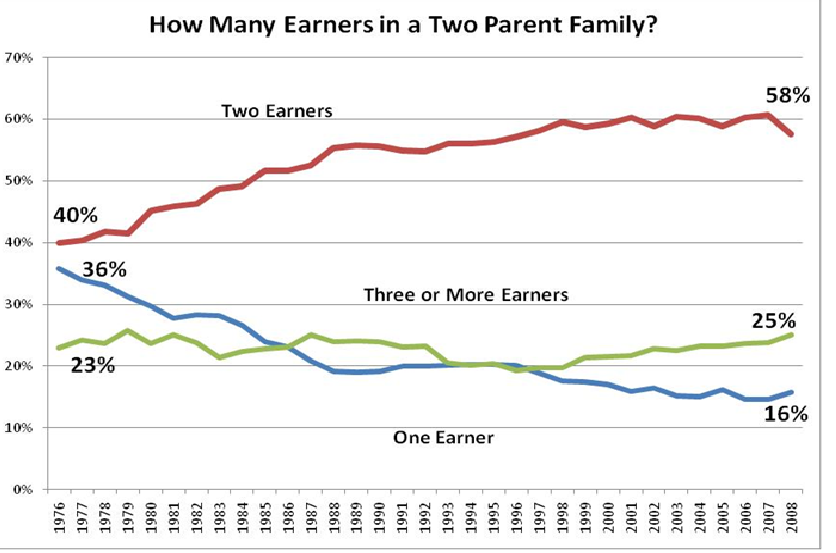

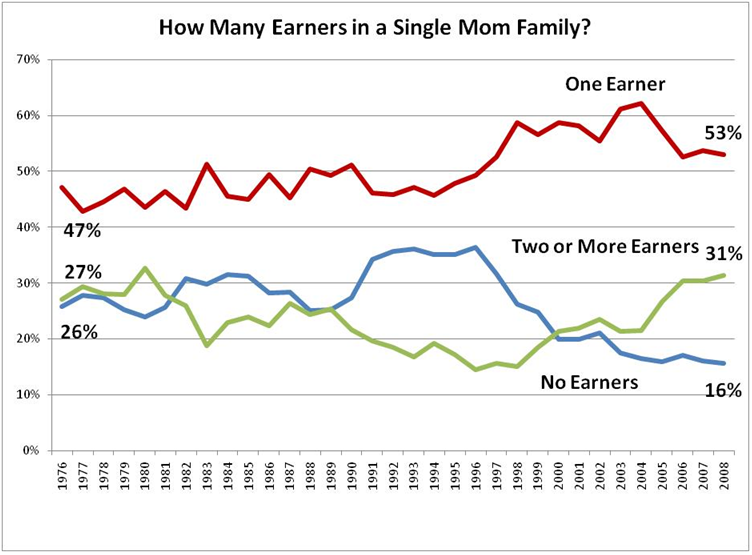

A quick glance at the following charts will show that, whether lone parent or two-parent family, families with children were working considerably more than in the mid 1990s, or even in comparison to the mid 1970s and mid 1980s, until the Great Recession came along in 2008. (The vast majority of lone parent families are headed by single mothers. About 2% of all families with children are raised by single fathers. The earnings gains that have been made in all families with children in the bottom half of the income distribution have mostly come by way of the extra paid labour of women. The real “success” story of lone parent poverty reduction Richards writes about is the reduction in the poverty rates faced by single mothers. That is partly a function of single mothers working more, and partly a function of more affluent women either breaking up with their partners or having kids on their own. Neither factor that might explain increase in median incomes of single mothers are attributable to public policy.)

Since, with rare exceptions, it takes two to get and stay in the comfortable middle, whether a single mom works or not is a indeed critical factor in her family’s finances.  The fact is, though, working may not be her ticket out of poverty. Many of the jobs created in during the job juggernaut of the decade 1997 to 2007 paid less than $10 an hour. Ontario actually grew its share of such jobs in that decade. As the single biggest labour market in the country, this is reason for concern.

Richards may discount the need for interventionist state supports to help reduce poverty among those who can work, but there has been a second notable factor behind the reduction of poverty among lone parents since the mid 1990s: the important increase in Canada Child Tax Benefits and the National Child Benefit Supplement, which has significantly raised the incomes of the poorest families raising children in every jurisdiction in Canada without income testing or variability across jurisdictions. (I’d add another graph here, but it’s getting a little unweildly!)

Instead of cutting back income supports to reduce “dependency” as virtually every province did in the mid 1990s, the federal program simply said: If you have children under 18, you need some support. The poorer you are, the more support you need.  This is not “soft” love. This is common sense. From 1998 until 2006, when the current government took office, there were important improvements to this program, notwithstanding the fact that more and more people were working. That’s because working may move you out of brutish poverty, but not out of a life filled with endless struggle to make ends meet.

Many analysts and politicians view a job as the best social policy. While there is much to be said for the virtues of work, it does not replace sensible and supportive social policy.

We have yet to see the impact of the Great Recession on household incomes, but if past recessions are any example, we will see up to 2 million nouveau poor added to the 3 million who were deja poor when the recession hit. (I’ll be publishing a report on this in the coming week.) As the Age of Austerity approacheth, let us hope that reports like this help define the limits of tough love, and provide incentives to gear up the many poverty reduction strategies in Canada. It is both achievable and affordable to reduce poverty for every group in Canada. Now that would be a success story worth writing about.

As Armine acknowledges, there’s little question that poverty rates, especially for single parents declined significantly during the 1996 to 2007 period. The key question is what had more impact: the pull of better employment prospects together with supportive services and positive impact of programs such as the NCB, or the push of tougher welfare rules and lower SA rates. This may be hard to prove either way, but there are some real weaknesses in Richard’s analysis and evidence:

The 1996 to 2007 period was a time of very strong employment growth, a “prolonged period of nearly uninterrupted economic prosperity†as he admits.

One of the key results that he bases his conclusion on is regression analysis showing that increases in the employment rate has more than twice the impact reducing LICO poverty rates in the 1996-2007 period than they did in the 1983-89 period.

He states he chose to use the employment rate rather than the unemployment rate because regressions using that had a higher explanatory potential, but from looking at the results, it appears he was pretty selective in his econometrics. He included a lot more explanatory variables in the 2nd equation which would then boost the measure of how well the equation fits. I’d like to see what the results for a similar equation using the unemployment rate were. (I expect he did them, but perhaps they weren’t as strong as so he didn’t report them.)

There may be an amount of correlation between “tough love welfare to work†policies and the employment rate because those policies boost the number of people entering the labour market and so prepared to accept work at whatever wage level.

During the late 1980s, the LICO poverty rate for single parents dropped by about 2 percentage points per year. That’s pretty close to the drop in poverty rates during the longer 1996 to 2007 period that he compares this to and of course the unemployment rate went even lower during this latter period, which would mean relatively more jobs for the harder to employ.

Another issue that Richard doesn’t deal with in his study is that going to work for a single parent takes them away from the home and from taking care of kids.

These poverty measures only deal with income levels and don’t take account of the expense of child care or raising kids. This raises two big questions: How much did the availability of affordable child care for single parents help with their ability to earn employment income? For those who don’t have access to affordable childcare and have younger children, are they really better ahead with higher employment incomes if much of this is going to pay for child care?

So there are major weaknesses in his report and conclusions.

As Armine says, we’ll have to see how poverty rates fare in the new age of austerity Richards concludes that Canada has probably reach the limit of welfare to work as a policy means to reduce poverty but he doesn’t have much in the way of answers for the nouveau poor.

Great piece, Armine.

Just because lone-parent poverty fell in the decade after Canada’s social policy approach to single moms changed doesn’t mean that the policy change drove poverty reduction.

I’m always boggled by analysis that points to a single factor (in this case, the tough-love social policies of the late 1990s) as the key explanatory variable when a host of other vary important changes are happening at the same time.

You point to increasing hours of work for women in all families, not only those that relied on assistance from the government, so obviously we have some societal-level change here. If anything, I’d speculate that the work-first policy change happened as a result of the fact that it was already acceptable (and common) for women with young children to work in Canada so it was just a reflection of the social trends rather than a driver of change.

We talk about single moms as a group but the single moms of the 21st century are not the same women as the single moms of decades past. For one, they’re better educated. They’re also likely older (I haven’t looked at the stats, but the average age at which women are having children is increasing overall). More of them are professionals choosing to take care of their children alone, rather than teenage moms whose boyfriend flaked out on them after they got pregnant. Just these changes in their characteristics would account for a lower poverty rate among single mothers as a group even in the absence of any social policy changes.

It would also be interesting to see whether there has been a significant change in the number of women who receive child support payments from the fathers of their children over that decade.

I am not an economist but I find Richard’s analysis quite stupid, and oblivious to the realities of raising children. Some of the comments above have pointed to this – including access to affordable child care, stronger child support provisions and (something an economist probably doesn’t understand) the changing nature of social norms.

To those who are economists: How are unemployment rates determined? Do they include those who may have been absent from the labour force (for whatever reasons, including for the sake of childrearing) for a period of time and are actively seeking employment? Do they include those who have worn out EI benefits and have been reduced to SA? And if SA recipients are included in those statistics, does it include those who are not seeking employment because of long-term illness or disability?

Do statistics on “new jobs created” ever say how many of those jobs are short-term? (I can only think of headlines in November shouting that there were hundreds of thousands of jobs created – but of course in the fine print, those are largely minimum-wage, part-time jobs in the retail sector to cover the expected Christmas crush.)

None of those stats make any sense to me until an economist can account for the 400,000 “permanent” jobs lost in the Ontario manufacturing sector – which were stable, secure, paid living wages and generally provided benefits like pharmacare, dental care, paid vacation and sick days (highly important when raising children).

Last, and on a personal note: In 1996 I was a single (not lone) parent of 2 children and my income was just about the LICO for that family size. I was not living in poverty and our lives were not deprived of any of the material benefits that this affluent society has to offer. This was about the time that benefits available to any household with children, personal financial situation notwithstanding, started to lessen and several years later, we were definitely living in poverty.

What were those benefits? A good public education system – why would I have chosen anything else but our neighbourhood public school? This also applied to the ability to involve my kids in summer and recreational activities. An excellent transit system – both within the city and between the cities. This made a car quite unnecessary. (And kept all of us healthier.) Whether provided by non-profit services or publicly available, we had good medical and dental care.

The public policy decisions that helped to put us into poverty were downloading, tax cuts, loss of funding for social housing, and reconstruction of EI.

The experience in all industrialized countries has been that work-for-welfare programs have been successful in reducing lone-parent reliance on government support. No doubt the buoyant economy of Armine’s thesis deserves credit. In the US, the EITC (Earned Income Tax Credit) should also be recognized as an innovative solution to the “cliff-effect” by providing low marginal income tax rates for incremental income.

The challenge for all countries is single never-married mothers as the fastest growing component of moderen family units. As shown by Armine’s chart, the earner mix component has changed leaving a notably high number of “no earner” single parent families- i.e. never-married moms. Data shows this segment absorbs twice as much in cash transfers as does the average family.

The social policy challenge is to develop an integrated cost-shared policy for child care and educational assistance to allow never-married moms to become productive members of society. Canada is a laggard in this regard.

I suppose I should read John Richard’s paper before posting a comment but…the incidence of welfare and poverty rates are only very loosely connected. Most households below low income lines are, as we know, working and many who are not working are reliant on non-welfare forms of support, such as CPP/D, Workers Compensation and other programs. Consequently, showing that employment has the biggest impact on reducing the incidence of low income has little to do with welfare policy so I don’t get the connection here at all.

In any case, I did a simple regression of the unemployment rate in Ontario against the percent of the population on welfare over the last 27 years and the R-squared was 80%, which is pretty darn high. This covers the period of Peterson, Rae, Harris and McGuinty. I think that this shows that none of the policies of any of these governments had much effect on the incidence of welfare: the main determinant of the number of people on welfare is the unemployment rate. The effects of other policy variables appears quite minimal.

Michael, your comment reminds me of my early years at the Social Planning Council of Metropolitan Toronto. I think it was called the Boston Miracle in the 1980s. They hacked welfare programs, and the welfare rolls dropped dramatically – just as unemployment rates went down all over the state. Duh.

A decade later it was the Wisconsin Welfare Miracle. Case loads cut in half because of reforms. IN this case I don’t know what was happening to the unemployment rate. But it’s possible to have a welfare “miracle” in the form of less cost for the state without actually solving poverty.

Last thought. The poverty rates being used are primarily LICO, a relative measure. How do we understand child poverty rates that are lower in PEI than anywhere else, or higher among children of Korean heritage than Aboriginal heritage? Well, if a population sub-group has a total distribution of earnings that is relatively low, the incidence of poverty is also very low – there’s just not that much further you can fall, relative to the others in this group. So poverty rates are higher when the population under examination has more inequality.