Industrial Policy, Manufacturing Employment, and the Loonie

The Institute for Research on Public Policy has published a very interesting overview study on the resuscitation of “industrial policy” in economic policy circles. It points out that industrial policy levers are used widely by countries around the world–despite hypothetical efforts (through trade deals and other institutions) to limit their application. The traditional Walrasian critique that government efforts to “pick winners” are wrong-headed and promote inefficient outcomes is holding less sway — all the more so in light of the deindustrialization, private sector underinvestment, and persistent trade imbalances that seem to be the legacy of Canada’s relatively laissez faire approach to industrial policy since the 1988 Canada-U.S. free trade deal. While I don’t agree with all of the IRPP report’s findings, it is a useful contribution to a debate that needs to happen. Other researchers in Canada are also looking in a more serious and balanced way at this set of issues; I especially follow the work of David Wolfe and Daniel Poon.

In fact, I prefer not to even use the term “industrial policy,” which seems to automatically convey images of large-scale “smokestack” industries and large government subsidies. In fact there are all sorts of sectors which are worthy of a wide range of pro-active interventions by government (not just subsidies) aimed at expanding their relative footprint in a particular jurisdiction. The reason for government getting involved is the important spillovers felt in other areas of the economy (investment, exports, productivity, and incomes) from a stronger domestic presence of desireable tradeable industries. This includes high-value tradeable services sectors, too (like business services, transportation, tourism, and even specialized public services like higher-level health care and education facilities which provide services to wider populations and hence have similar characteristics to other “export-oriented” sectors). In my work for the Alternative Federal Budget and other outlets on this issue, I have tried to use the term “sector development strategies” rather than industrial policy.

Another counter-argument to pro-active sector strategies is the claim that manufacturing employment is declining universally, so there is no point trying to stand in the way of it. There are indeed strong reasons why manufacturing tends to account for a smaller share of total employment over time: faster-than-average productivity growth, a gradual shift of demand to services (due to a higher income elasticity of demand), and others. But those trends don’t explain why manufacturing output should shrink in absolute terms (as it has in Canada since 2006). And it is clear that Canada’s share of manufacturing has shrunk markedly over the last decade — relative to global manufacturing output, and relative to our own purchases of manufactured goods. For example, Canada’s trade balance in manufactured products deteriorated from approximate balance a decade ago, to a large and chronic deficit of around $100 billion per year today. By this measure, Canada’s deindustrialization during the high-loonie era has been uniquely dramatic (and painful), and cannot be attributed to a universal trend.

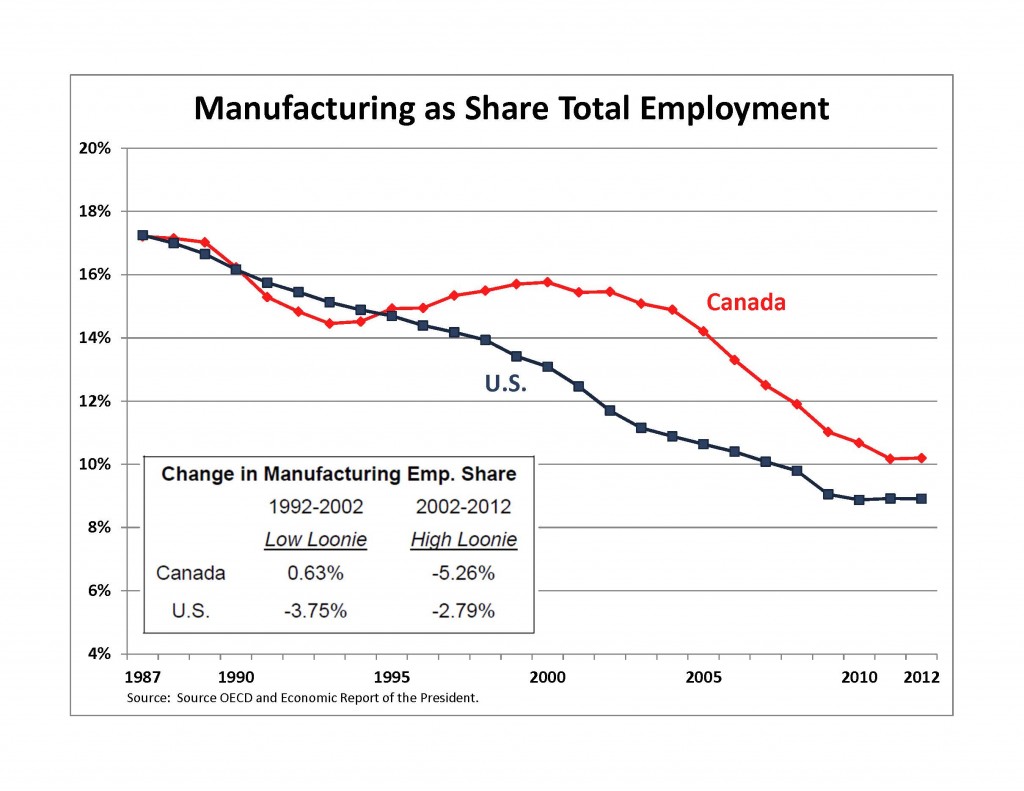

More evidence on this score is provided by the following graph, which plots manufacturing employment as a share of total employment in Canada and the U.S. During the low-dollar 1990s, Canada created manufacturing jobs slightly faster than the growth in the overall labour market (while the U.S. was deindustrializing). Since 2002, however, when the global commodities boom (and foreign investors’ hunger for Canadian petroleum assets) took off and the dollar appreciated, Canada has lost manufacturing jobs (relative to total employment) almost twice as fast as the U.S.

And compared to some other OECD countries, our relative share of manufacturing employment (now just above 10%) is low. Manufacturing accounts for 20% of employment in Germany, and 17% in both Japan and Korea. These countries also face the same “inexorable” trends in manufacturing employment as Canada, and the same pressure from low-cost emerging exporters — yet they have managed to hang onto a higher proportionate share of these high-productivity, high-income jobs.

And compared to some other OECD countries, our relative share of manufacturing employment (now just above 10%) is low. Manufacturing accounts for 20% of employment in Germany, and 17% in both Japan and Korea. These countries also face the same “inexorable” trends in manufacturing employment as Canada, and the same pressure from low-cost emerging exporters — yet they have managed to hang onto a higher proportionate share of these high-productivity, high-income jobs.

I think the strategic importance of manufacturing (and other high-value, export-oriented, innovation-intensive sectors) is coming to be better appreciated by policy makers who were unduly influenced by the “hands-off” arguments of recent decades. Hence this is a fruitful time for progressives to be fleshing out our arguments for the sorts of sector strategies that could play an important role in coming years.

Doubtless there were and still are lots of people, even policymakers and economists and rich people, who actually believed all that Walrasian stuff. But at some level it was always an excuse. That schtick would never have become popular if the wealthiest didn’t want reasons why it was OK for them to shift manufacturing to low-wage sweatshops, move money out of low-profit manufactures and into high-profit but useless financial speculation, and so forth.

Even as the embers of the financial crisis and great recession burned brightly we heard the meme from talking heads to stay the course on ‘free trade’ and not embrace protectionism. Such advice effectively misleads the conversation away from what matters: people of the medium and lower classes with a living wage and benefits not living as a precarity: empowering this group is the best precondition for a society with sustainable growth and stability.

This is neither a call for autarky nor a plead for handouts to the poor but a warning about how opinion from the media constantly channelled to the populace constantly frames ‘industrial policy’ as always and everywhere about the ‘picking of winners and losers’ by citing cases such as Solyndra.

What we collectively fail to recognize is that the innovations of today (with latency) become the source of decent paying jobs of tomorrow. This is why government funding in productive investments is important; there doesn’t have to be a funneling to select companies.

We have a chicken and egg syndrome: inadequate effective demand inhibits innovation on the supply side. The pile of dead cash in corporations is testament to that. With the conventional embrace of supply side solutions we end up being focused on just being ‘efficient’ –ostensibly more productive- which ultimately results in off-shoring thanks to the trade regimes we function under.

But efficiency only gets us so far especially in an increasingly Innisian economy like Canada’s. Remember that at one time innovations from the internet, telecommunications, roads, electricity grids, and railways had no “ROI†before they became essential to modern living. We need to do more as a society to agree to invest in the highways (information and real) of tomorrow.

Thanks for the links to papers of David A. Wolfe and Daniel Poon.

It’s a breath of fresh air midst the staleness of pro-market/privatization discourse to read those words “industrial policy.” In terms of the past, this new report mentions the national policy of the 19th into the 20th century, but fails to note how successful it was. With massive exports of wheat and building (overbuilding) of railways with massive government intervention, Canada industrialized rapidly behind tariff walls and, with highly elastic supplies of labour and capital, no damage was done to exports or to industry. Not a hint of Dutch disease! Much more recently in the 1960s and particularly the 1970s, government policy was evident in the creation of the Autopact, Foreign Investment Review Agency, Canadian Development Corporation, the Science Council of Canada and the National Energy Program. In retrospect the 70s was the decade of transition, from Keynesian policies to neo-liberal policies, with industrial policy being re-articulated and then destroyed. On the left James Laxer as director of research for the Federal NDP and David Wolfe as a major economic player in the Ontario NDP government, pushed for industrial policy, but the march of neo-liberalism – backwards into the future – could not be stopped. The latter may no longer be true. There us, once again, an alternative. If so, it has important political implications. There is general agreement that it’s economic policy that drives the Harper government and accounts for its popularity, in spite of the scandals, with voters. There’s on opening here on the left, at both the federal and provincial level, to put forward a concrete alternative to Dutch disease. More free trade agreements, which is about all that Harper has on offer, risk a path dependency that is not working in terms of job creation and increasing wages, and further tie the hands of governments. There might even be an alternative where the federal government, in liason with the provinces, promotes an east-west pipeline, though only within the context of a tough policy on carbon emissions and imaginative industrial policies.

Canadians have a choice, shall we be hewers of wood & drawers of water or a 21th Century Techno-industrial Super Power?

The choice is ours.

If we continue along our current path we choose the former, if we adopt a 21st Century updated & improved version of the “Canadian National Policy” it is the latter.

Rent yielding asset (both natural & legal monopolies) should be nationalized or heavily regulated & taxed in order to lower costs rather than leaving economic rents to be taken by private entities.

Taxation must be shifted off labour/business/industry (production) and onto Economic Rents (privilege) with the goal of keeping prices inline with the cost of production.

The aim of public infrastructure & taxation should be to keep prices down to what is technologically necessary, lowering a nation’s cost of doing business & increasing international competitiveness.