OECD Findings on Employment Protection and Jobs Performance

Further to my earlier post on the OECD’s new data on employment performance across its 34 member countries (and Canada’s relatively poor ranking in that regard), another part of the OECD Employment Outlook 2013 that is also worth reading in detail is Chapter 2. It provides a thorough revision and updating of the OECD’s quantitative index of EPL intensity. It contains a useful summary of the mainstream literature regarding EPL costs and benefits (which would have benefited, however, from inclusion of some critical, heterodox voices), as well as a detailed review of the revised methodology behind the OECD index.

The actual country scores for the index do not seem to be reported in the chapter, but they are available through the OECD’s key table database.

The key findings of Chapter 2 include:

- EPL is generally stronger regarding mass layoffs than individual dismissals.

- Cross-country variations are especially wide regarding regulations on temporary work and temporary agencies (Canada has almost no regulations in this area).

- Countries in the common-law tradition (including Canada) generally have weaker EPL.

- Countries with stricter rules regarding termination generally had stronger rules regarding other labour market regulations (duh!).

- There is a clear trend toward weakening of EPL standards, with over one third of OECD countries cutting their standards since 2008. (There has been no change either way in Canada’s rules during this time.)

Canada ranks consistently at or near the bottom of the list on almost every one of the 21 criteria considered by the OECD in their index, including:

- Notice & severance pay

- Procedural inconvenience

- Difficulty of dismissal (individual or collective)

- Protection against dismissal (individual or collective)

- Regulation of temporary contracts

- Regulation of temporary agencies

On the actual scores, Canada ranks near the bottom of each of the 4 broad categories considered by the OECD. A simple average across those 4 categories gives Canada a score of 1.4 (out of 6), compared to an OECD average of 2.325. That puts us 32nd out of 34 (only New Zealand and the US have weaker EPLs).

The standard neoclassical story is that stronger EPLs will actually inhibit the “flexibility and efficiency†of market forces, resulting in less and poorer employment in the long-run (self-defeating, with respect to the nominal purpose of EPL, namely “protecting employmentâ€). There’s no evidence of that correlation in the OECD data, however. The US, of course, has had one of the worst-performing labour markets in the OECD in recent years – despite its extremely weak labour protections in all areas. Other countries with strong EPL have achieved very good labour market outcomes (such as Germany).

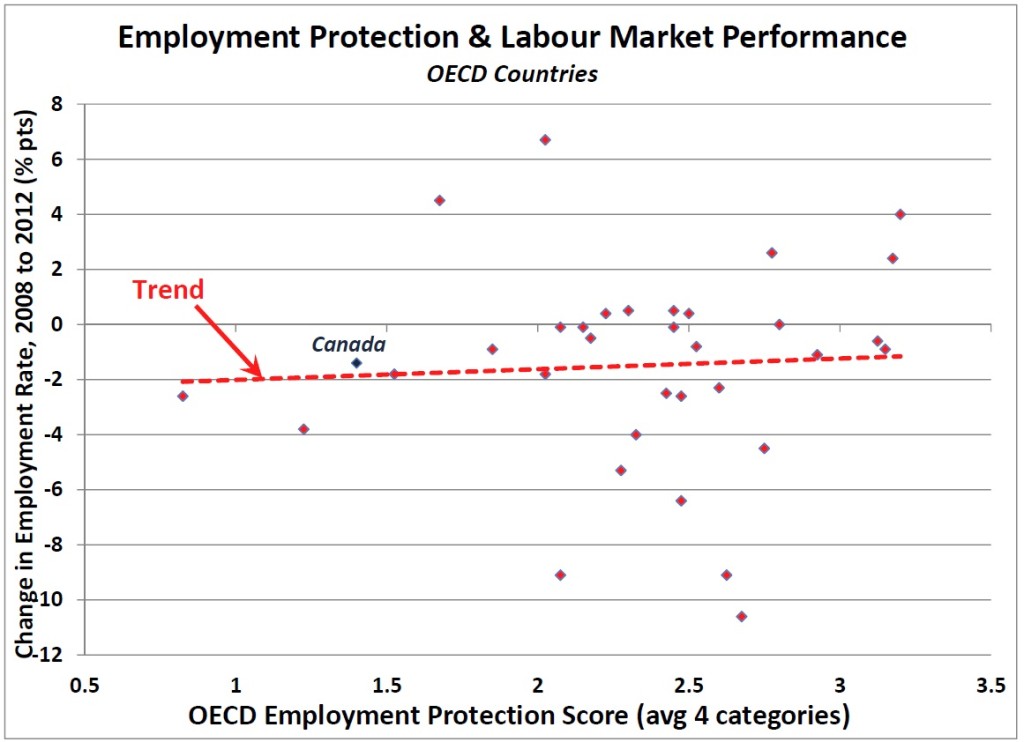

A simple comparison of the average EPL score for each country versus the change in its employment rate from 2008 through 2012 (also reported in the OECD Employment Outlook’s statistical annex) is provided below.

There is no statistically significant correlation between intensity of EPL and labour market performance. According to the neoclassical story, there should be a clear negative pattern to the graph (with countries with weaker EPL enjoying stronger jobs growth relative to population). In fact, the linear trend of the 34 observations suggests a weak (statistically insignificant) positive relationship. The 7 OECD countries with the strongest EPL frameworks according to the OECD all had better employment rate outcomes than Canada did since the recession hit in 2008. In 3 of those cases (Germany, Luxembourg, and Turkey), the employment rate actually increased.

Perhaps restricting the power of companies to terminate existing workers, and replace them with precarious staff, actually is good for the labour market after all. It is certainly good for workers.

One should keep in mind that:

1. The OECD survey, as best as I can tell, doesn’t take into account that 30% of our workforce is unionized (we don’t get extra points versus a country with a lower unionization level)

2. The OECD survey from my reading (e.g. questions 3A,3B,3C,4A,4B,4C) only considers statutory entitlements, but not common law ones. So, notice/severance requirements in Canada’s common law jurisdictions can typically be much higher than statutory minimums, but this isn’t considered. I view this as a methodological flaw.