What happened to the recovery?

(The following is slightly adapted from a short piece on page 3 in the new issue of Economy at Work, the quarterly publication I produce for CUPE, which also covers a lot of other relevant issues.) Â

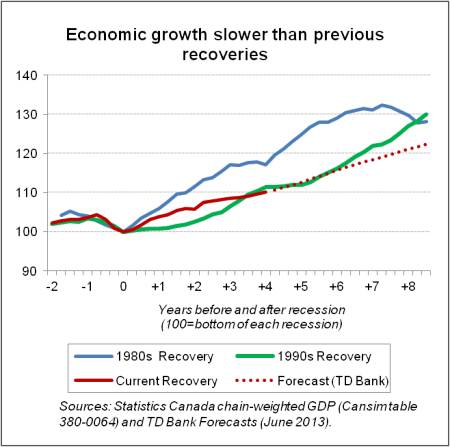

It’s been a little over four years since Canada’s economy bottomed out in mid 2009. While we didn’t suffer as deep a recession as many other countries, growth has been slower than previous recoveries. Many are still waiting for the recovery to take hold.

Stimulus spending ensured that the downturn wasn’t as severe as it could have been and growth was stronger coming right out of the recession, but since then government austerity has slowed economic growth, putting us behind the even the 1990s recovery (see chart below).

While governments cut spending deeper in the mid-1990s, declining interest rates and a much more competitive dollar led to a surge in exports.   That’s not in the cards this time. Instead, interest rates are going up, putting a damper on growth and with the rest of the world in the doldrums, our net export situation has got worse. Canada may be open for business, but few are in the position to buy.

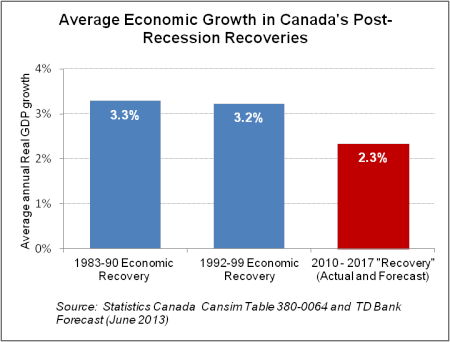

Our current recovery isn’t expected to pick up much speed, either. Forecasters expect growth to rise to about 2.5% in the next two years, but then to wane to about 2.3% for 2016 and 2017.  The Bank of Canada’s senior deputy governor Tiff Macklem recently revealed that the Bank of Canada has downgraded its growth forecast for this year.

Overall growth in this “recovery†is expected to average just 2.3 per cent a year from 2010 to 2017. That’s almost a full percentage point lower than the 3.2 per cent average for similar recovery period in the 1980s and 1990s (see chart below).

If this recovery matched the growth rate of 1980s and 90s recoveries, Canada’s economic output would be $100 billion and 5 percentage points higher by the end of 2017 than it is currently forecasted to be.  This missing $100 billion works out to about $6,600 less per household: not a great present for our sesquicentennial.

Is this the new normal: slower growth?  It doesn’t need to be. There’s lots of excess cash on the sidelines or in speculative investments that would do more good if channeled into productive and social investments—or in the hands of households.

I am old enough to remember when it was hard for an ordinary worker like me to get quick and easy access to alternative or progressive economic analysis – so thanks so much for this. It is great to be able to take 5 or 10 min out of my busy day to stay up to speed.

“It doesn’t need to be. There’s lots of excess cash on the sidelines or in speculative investments that would do more good if channeled into productive and social investments—or in the hands of households.”

If the private sector is not spending, and net imports are draining domestic demand, then the federal government will have to run larger budget deficits.

Australian economist Bill Mitchell explains:

At last count there were two broad macroeconomic sectors – the government and the non-government. The non-government sector can be decomposed into the private domestic sector and the external sector. The private domestic sector can be further decomposed into households who consume and firms who invest (in productive capital).

Macroeconomics is easy – thats it! 2 broad spending sectors and then some more detail.

What do we know about these sectors in the US?

1. Households are not spending enough on consumption – and why should they given they have to reduce their unsustainable debt levels and are saving to generate buffers just in case they are next to join the unemployment queue.

2. Business firms are not spending enough on investment – and why should they given they have to reduce their unsustainable debt levels and that household spending is not pushing production levels beyond existing capacity (by a long margin).

3. The external sector is deteriorating – that is, spending is contracting because the Europeans and the Brits are killing growth in their economies.

How many more spending sectors are left in the US?

The most basic macroeconomic rule – spending equals income. When someone spends another gains income. When a sector increases spending, other sectors enjoy the rise in income.

So if all these non-government sector spenders are being cautious and the private domestic sector is attempting to save overall – and – the world economy is not going to drive US exports very hard – where is the deficit spending going to come from to drive growth?

There is only one source – government budget deficits.

(A veritable pot pourri of lies, deception and self-serving bluster at http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=20782)

This is what confuses me. If there is plenty of cash out there then why do we as a society regularly rely upon our government to spur the investment. No matter what political colour you are our governments to a very poor job of this.

Example;

the majority of us have realized alternative energy (green) is a necessity for our society to be sustainable in the long term.

Yet (in Ontario specifically) the OLP has proven very efficiently that they are terrible at 1. rolling out new initiatives and 2. managing those initiatives.

Literally millions of dollars have been wasted at the hands of our provincial government.

On the federal side of things so little has been done to spur (green) that we are consistently viewed on the world stage as a deplorable greenhouse contributor.

Yet private industry refuses to make the investment and get things done the “right way”

I apologise for the OLP green strategy rant, but it serves my purpose.

Private business does not act until governments dangle a very inefficient carrot in front of them. What happened to capitalizing on a capitalist economy?