More on Demographics, Demand, and Canada’s Falling Employment Rate

My post last week on the continuing decline in the employment rate in Canada (to below 61.5% in April, barely higher than the low point reached in the 2008-09 recession) has sparked some continuing discussion about the role of demographic change in explaining that decline (as opposed to a shortage of labour demand).

Is the decline in the employment rate due to weak labour market conditions, or is it due to the ageing of the workforce (as a result of which a larger share of the working age population consists of people in older age categories which normally have lower labour force participation and employment incidence)?

The answer, obviously, is “Both.” The ageing of the Canadian workforce is a decades-old trend, it did not start in February 2008 (when the overall employment rate peaked at 63.8%). Until then, the ageing of the workforce did not prevent the overall labour market from enjoying higher employment rates over time. The downturn in the business cycle did start in 2008. So it’s reasonable to conclude that this turn likely reflects cyclical (not structural) factors.

We can try to sort out the two forces at play by disaggregating the employment rate numbers by age category. My methodology in analyzing the overall decline in the employment rate was to compare today’s rate to the pre-recession peak, and then estimate how much more employment would be required to get back to that pre-recession employment rate. I interpreted that as a broad measure of the amount of new employment required to truly repair the damage from the recession. That approach is certainly more reasonable than the argument made by the federal government that since absolute employment today is higher than it was before the recession, all the damage done by the recession has been repaired; this argument ignores 6 years of population growth which added over 2 million Canadians to the working age population.

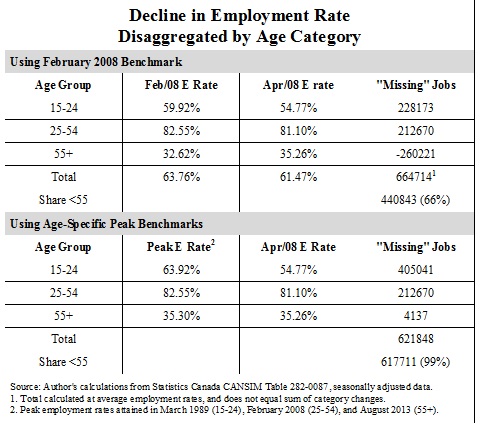

Now let’s replicate my analysis, but disaggregating the employment rate data into broad age categories. Young workers (15-24) have experienced the worst decline in employment incidence. So-called “core” workers (25-54) have experienced a more modest decline. Older workers (55 and over) have experienced a higher employment rate. Whether this is good or bad depends on how many of these older workers are choosing to work longer for positive reasons, and how many have been compelled to stay in their jobs by reduced or less secure pension incomes.

The first part of this table shows that for the two under-55 categories, a total of 441,000 additional jobs would be required to rebuild the two under-55 employment rates back to their respective February 2008 levels. That represents two-thirds of the total 665,000 missing jobs I had estimated on the basis of the analysis of the aggregate 15+ employment rate. (Because of the shift-share phenomena discussed above, the total “missing” jobs does not equal the sum of the age category “missing” jobs.) In other words, two-thirds of the deterioration in the overall employment rate since 2008 can be ascribed to the deterioration of employment incidence among under-55 workers — and hence can’t be directly attributed to demographic change. Perhaps the rest of the 665,000 jobs could be attributed to demographic ageing, offset somewhat by the rising employment incidence among the 55+ category.

Another approach, that would more closely replicate the spirit of my aggregate analysis, would be to separately locate the peak employment rate experienced within each age category, rather than using the peak employment rate for the aggregate 15+ labour force (which was February 2008). After all, if we’re going to disaggregate current employment performance by age group, we may well wish to also disaggregate the parallel task of measuring the extent to which current employment falls below peak (or potential) employment incidence. This exercise is summarized in the lower part of the table.

The peak employment rate for the “core” 25-54 age group was attained in February 2008, so there is no difference for that group. The peak employment rate for young workers was attained back in 1989 (the employment rate for young workers in 2008 was still almost 4 percentage points below that peak, reflecting both higher youth unemployment in 2008 than 1989 and lower labour force participation, presumably due mostly to higher participation in post-secondary education — although PSE enrollment itself partly reflects weak employment opportunities). The peak employment rate for the over-55 group was attained in August last year; even in this group the employment rate has declined in recent months.

Comparing the actual employment rate to the historical peak rate within each category, leads to a combined estimate of “missing” jobs of 622,000 positions — almost all of which were borne by the two under-55 age groupings (since older workers are experiencing close-to-peak employment rates). That’s not hugely different from the 665,000 missing-job estimate I derived on the basis of the overall population. The takeaway from this analysis: Even adjusting for the ageing of Canada’s workforce, the economy would need a total of 622,000 more jobs to bring up the employment rate (for each age category of worker) to its potential (based on peak attained employment rates).

I certainly accept that demographic change is part of the story of Canada’s falling employment rate. That being said, however, I think the following take-away conclusions are valid:

-

The decline in the employment rate is due more to weak employment demand than to demographic change.

- The decline in the employment rate is clearly visible in young and core workers.

- Employment in Canada among workers under 55 is hundreds of thousands positions (from 441,000 to 618,000, depending on your choice of benchmark) below what it would be if previous peak balances between workers and jobs were re-attained today.

- And since the pre-recession benchmark was not itself a position of full employment, the true problem of underutilization of labour in Canada is even greater.

Labour force participation among under-55 workers has also declined significantly (this is not reported in the table), and so far in 2014 has averaged its lowest levels in both age groups (15-24 and 25-54) since 2002. Overall labour force participation (among all people 15+) is at its lowest level since 2001. So the decline in labour force participation (like the decline in the employment rate) is mostly due to factors other than demographics (presumably, weak labour demand).

The phenomenon of rising participation and employment among older workers is an important one that needs lots more analysis. Indeed, it is trickling over into the decline in employment rates among the youth and core age groups. In a demand-constrained labour market, younger workers always bear a disproportionate share of the burden of un- and underemployment (reflecting last-hired first-fired effects, etc.). Therefore, while much of the decline in employment incidence among under-55 workers reflects weak overall labour demand, some of it also reflects a redistribution of employment from younger to older workers. This is a perverse result for many economic and social reasons, and should lead us to question policies (like postponing the retirement age to 67, and other restrictions on early retirement) which are helping push up employment rates among older workers.