Indigenous Workers in Canada

Labour market data in Canada is easily available by sex, age, and region. We spend a great deal of time talking about these factors. More recently Statistics Canada made labour market data available on CANSIM by landed immigrant status, going back to 2006. This factor is less often included in most labour market analysis, and too few know that it is even available.

But if you want to know how racialized workers or Indigenous workers (First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples) are doing in the labour force you basically have to rely on the census … oh, wait. And on top of eliminating the census, the Harper government shut down the First Nations Statistical Institute.

So imagine my delight when a recent search on the issue turned up an article from the Centre for the Study of Living Standards about Indigenous employment that cited the Labour Force Survey as a source.

I should have already known that the Labour Force Survey asked an Aboriginal identity question, but I didn’t. A quick call to Statistics Canada revealed that this data is freely available on request, but is limited to First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples living off reserve (since the LFS doesn’t survey persons living on reserves).

I plan on doing a more thorough analysis, but I thought that I would post a few quick insights, and get the word out so that anyone who is interested can call and get the data for themselves.

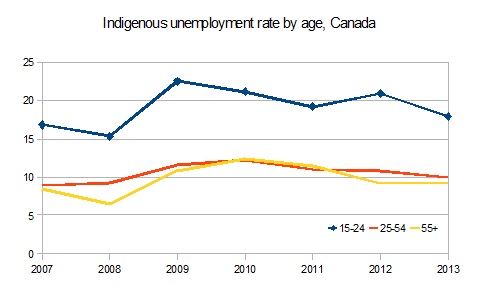

Some of this data confirms things that we ‘know’, but having the hard numbers helps when we’re calling for action. For example, unemployment is a HUGE issue for Indigenous young workers living off reserve, before, during, and after the recession. The unemployment rate reached a high of 22.5% in 2009, and was still 18% in 2013.

While I don’t have the data to calculate underemployment, consider that underemployment rates seem to be about double unemployment rates for the general population. That suggests an underemployment rate of at least 36% for Indigenous young workers in 2013.

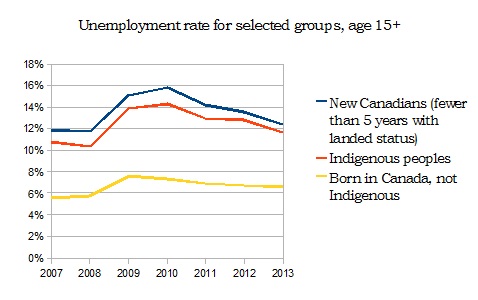

Unemployment rates for Indigenous workers are much higher than for non-Indigenous Canadian born workers, and are comparable to that of new Canadians.

As you can tell by the graph, the recession was more severe and lasted longer for Indigenous workers and new Canadians.

So whenever we’re talking about labour market strategies and good jobs, it’s important to keep in mind that for some workers there are systemic barriers that need to be addressed. Hopefully access to labour market data for Indigenous workers and new Canadians can be one way that we convey the need for action.

If you want to read more about Indigenous workers and the labour market in Canada the CSLS has a study using LFS data from 2007 – 2011, the Conference Board of Canada has a more employer driven study from 2012, and a 2011 paper in aboriginal policy studies by Friedel and Taylor analyses the colonial discourse in Indigenous labour market development policy in Northern Alberta.

One answer to the high rate of aboriginal unemployment is a job guarantee whereby the federal government would act as employer of last resort, buying the unused labour (at minimum wages with benefits) of anyone willing and able to work. These jobs could be delivered locally and might include provisions for care of the elderly and disabled, education and activity for young people, arts and cultural performances and projects, and initiatives for environmental protection.

This job pool would rise and fall counter-cyclically to the needs of the private business sector, and would anchor prices and inflation with an economic tool less brutal than forcing people to lose their jobs through austerity. There are many precedents for public service employment. In 1944, the Canadian unemployment rate dropped below 1% because one out of every three adult males was in government service. Far from destroying the economy, deficit spending led to years of post-war growth and prosperity with a trained and disciplined workforce.

The anemic job growth we see today is a consequence of federal government budget cutbacks that fail to support the private sector and are exactly the opposite of what the economy needs. Good financial managers would never tolerate a massive waste of the country’s human resources and the suffering caused by income deprivation and damage to self-esteem.

Footnotes:

1.What is a Job Guarantee?

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=23719

> But in general, there cannot be inflationary pressures arising from a policy that sees the Government offering a fixed wage to any labour that is unwanted by other employers. The JG involves the Government “buying labour off the bottom†rather than competing in the market for labour. By definition, the unemployed have no market price because there is no market demand for their services. So the JG just offers a wage to anyone who wants it.

2. Public service employment programs – what really have we got to fear?

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=20679

3. What was Canada’s main contribution to World War 2?

http://wiki.answers.com/Q/What_was_Canada%27s_main_contribution_to_World_War_2

> By the end of the second world war, Canada had ONE MILLION, ONE HUNDRED THOUSAND MEN IN UNIFORM. That is one out of every three adult males.