Transit costs are too darn high

Public transit is a key piece of urban infrastructure, important for getting people where they want to go while limiting congestion and pollution. A central part of the federal government’s infrastructure plan involves expanding and improving public transit, through their newly established Public Transit Infrastructure Fund.

Note that Budget 2017 allocates some amount of the total public transit funding to the Canada Infrastructure Bank, the Smart Cities Challenge, and Superclusters (really?), so I have only included the amount committed to the Public Transit bilateral agreements here.

This falls short of what the Green Economy Network recommended – we estimated the need to be closer to $1.76B annually from the federal government (Table 2), which would lead to a reduction of between 11-20 Mt of GHGs annually, but we are talking about committing serious funding to transit, which is good.

The language around the investment in public transit focuses on reducing congestion, lowering GHGs, and shortening commute times, all issues that the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM) identified in their transit campaign. What isn’t mentioned though, is affordability.

And the cost of a monthly transit pass is, frankly, too. darn. high.

Which is why commuters across Canada were not pleased when Budget 2017 eliminated the (non-refundable) tax credit which allowed users to claim monthly transit passes. While the tax credit wasn’t perfect, it did do something to defray the cost of transit for about 1.7 million transit users.

The justification given by the federal government for getting rid of the tax credit is that it mostly benefited higher income families, and had no measurable impact on increasing ridership. Since it is a non-refundable tax credit (you don’t get anything if you don’t have taxable income), it likely didn’t benefit low income families much. But it is for public transit, so one would guess it benefits the middle of the spectrum, rather than high income folks.

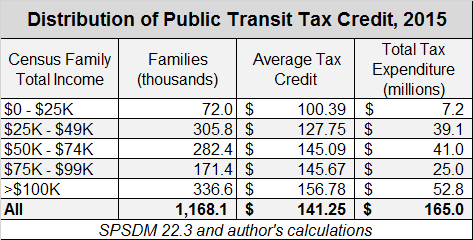

The tax credit could be shared between spouses and their children under 19, so the relevant unit of analysis here is a census family.

You can see that higher income families get a higher average return from the tax credit, and that about a third of families benefiting from the credit have household incomes over $100K. But interestingly, about half of the total tax expenditure is for families with a total annual income below $75,000, and half is for families with incomes above that amount. Median total income in 2014 was $78,870, so that’s a pretty fair distribution for a non-refundable tax credit.

On top of this, there were other tax credits with more skewed distributional benefits that were left untouched. No wonder Toronto and Vancouver transit users are crying foul.

How about a gender lens? According to CRA T1 Final Statistics for the 2014 tax year, women made up about half of the taxfilers claiming the public transit credit. What’s interesting is the age distribution – slightly more men in core working age groups claim the credit, but both older and younger women outnumber men in their age groups.

With all of that in mind, what kind of policies would a social democrat like myself suggest?

First, I would recommend that some amount of the infrastructure funding be tied to affordability. Some provinces and / or municipalities have subsidized passes, but the current system is failing many low income transit users, and getting out of range for even median income folks.

Secondly, if I were going to eliminate the tax credit entirely, I would at least wait until Phase 1 of the transit infrastructure plan was complete. Removing the subsidy from riders before the spending has had a chance to show improvements to the system could hurt ridership and revenues during this rebuilding phase.

If I wanted to keep the tax credit, I would modify it so that it is refundable, individual, and phased out at higher incomes (say, anything over the median income).

Finally, I would look at ways that we’ve prioritized cars in our cities. Policies such as congestion pricing could raise revenues to support public transit, and provide an added incentive for car users to switch to transit.

This is a great example of how policy design needs to keep distributional impacts in mind, so that we’re not further hurting low income families as we’re racing to meet our commitments on climate change.

Thanks for the post Angella.

I liked your emphasis on the importance of distributional impacts in deliberative policy actions related to lowering GHG emissions.

This is one of the aspects I focused on my January PEF blog related to the Ontario electricity sector. Electricity price increases have had a very regressive impact, with low-income households paying a proportionately high percent of their income on electricity. As explained therein, one of the main elements driving price increases was related to how the Liberal Government privatized and administered the introduction and growth of renewables in the supply-mix, including with the stated objective of reducing GHG.

You may be aware that here in Toronto we had a recent and very topical example of your point regarding prioritizing cars. With respect to congestion pricing there was a disagreement between Provincial and municipal jurisdictions and a lively political debate, including among progressives. One of the main “cons” was the equity aspect of congestion pricing. Politics aside, I think it is an empirical question whether or not congestion pricing in Toronto (or any large city with transit alternatives) would or would not be regressive, neutral or progressive, and if regressive, the extent of such regressivity and whether the equity costs trump the efficiency gains. Further, a number of cities that have introduced some form of congestion pricing have also built-in affordability programs to assist low-income drivers (e.g. Los Angeles.).

Exactly, Edgardo, thanks for your comment. I know that my suggestions on both affordability and congestion pricing are pretty vague here. And congestion pricing in particular is tricky to get right – a topic for another post!

If you want to promote transit, the best way to do that is to improve service, rather then reduce the price. Transit is already a lot cheaper then automobiles. The reason people don’t use it is because of a lack of service.

If you want to help low income people with thier transportation needs, then increase thier income. Then they will benefit even if they cycle or walk.

It is somewhat cheaper, but not necessarily a LOT cheaper. I remember crunching the numbers and coming to the conclusion that for my wife and I, commuting two in one car is in fact cheaper than taking transit. Now mind you, that’s in a car that’s already paid for with pretty good mileage and a safe driver with pretty cheap insurance. But still.

The tax credit is 15% of the total bus pass costs. If your monthly transit pass costs $100, the amount you can claim in 2008 would be $1,200, resulting in a tax credit of $180.00 (twelve months multiplied by 15%). Most working people would be getting money back.

Hi, Taxman, thanks for your comment. Since it’s a non-refundable tax credit, people would only get money back if they have taxes owing – if you are earning minimum wage or near minimum wage, you wouldn’t have any taxes owing, and so you wouldn’t get any money back. Or if you earn slightly more, but have other tax credits (childcare, medical expenses, tuition, etc).

Many good points in this post. Much of the analysis I have read about the elimination of this tax credit seems to ignore, or at least cloud, the original policy basis. Obviously, the measure was never intended to make transit more affordable for low income earners who do not pay taxes. Other measures are in place, or should be in place where they are not, for that purpose. This non-refundable credit was designed to target taxpayers who earn substantial income and are therefore most likely have a choice of using transit or a personal vehicle. While the efforts to measure behavioural change over the life time of the tax credit show only a small percentage increase in overall ridership, more relevant measures would be the percentage of additional transit users who have the option of driving a personal vehicle and the percentage of additional riders who can benefit from the tax credit. This is the target group for the tax credit and should be the focus of analysis when assessing its success or failure. Measuring the increased ridership attributable to the credit is quite difficult. Indications are that it was small. I would only comment that changing behaviour such as this can take a generation. The credit was one measure to create a culture that encouraged use of public transit among those who have a choice to use it. Although I am not a fan of these tax credits in principle because of the associated administration, I think the analysis should have the proper focus.

Neil, you are absolutely right about the tax credit’s intended purpose when it was introduced, and the government’s analysis was that it did little to increase ridership. I agree that changing behaviour takes time, and investments that improve services.