Statistics Canada’s Ongoing Consultation about the Market Basket Measure Needs Recalibration

Things are moving quite fast, even too fast, since the federal government’s first poverty reduction strategy was published in August, at least for the aspects of this strategy which are problematic. The unilateral decision to consider the Market Basket Measure (MBM) as “Canada’s Official Poverty Line” is one of those. It ignores some useful expertise developed about the MBM over the years, notably by the Centre d’étude sur la pauvreté et l’exclusion (CÉPE), the institution meant to provide dependable and objective information on matters concerning the application of Québec’s Act to combat poverty and social exclusion[1], as well as current discussions about the type of living standard effectively assessed by this measure.

In 2009, the CÉPE carefully recommended the use of the MBM “as the baseline measure to monitor situations of poverty from the perspective of coverage of basic needs” (CÉPE’s advice, page 34), stating explicitly that “while the market basket measure makes it possible to monitor the evolution of poverty and the progress achieved, it fails to measure exit from poverty, as based on the definition contained in the Act” (Ibid.)[2]. Yet the definition of poverty given in the federal strategy is quite close to the Québec one[3].

Moreover, the federal decision was announced without waiting for the results of the periodic revision of the MBM (rebasing process) by Statistics Canada, which is still taking place. This decision is now on its way to be legislated through Bill C-87, which was launched on November 6 (and incidentally, does not mention the strategy’s definition of poverty). Meanwhile, Statistics Canada has launched an online consultation asking people’s advice on the MBM… with ill-calibrated data.

Let’s start with this point, since the consultation is ongoing and invitations to respond are circulating within different organizations.

What’s wrong with Statistics Canada’s online MBM consultation

In this survey, held from October 15, 2018 to January 31, 2019, Statistics Canada “is conducting a consultation to gather input from Canadians to help validate how we are measuring poverty”. The ambiguity between the federal government’s haste to set the MBM as the official poverty line and the periodic rebasing process of the MBM by Statistics Canada is ubiquitous in the survey’s presentation, whose stated purpose is “to help validate the methodology of the MBM”:

“Recently, the Government of Canada announced that the Market Basket Measure (MBM) will be used as Canada’s Official Poverty Line. Statistics Canada is currently conducting a comprehensive review of the MBM.

The MBM is a measure of low income which is based on the cost of a basket of goods and services that individuals and families require to meet their basic needs and achieve a modest standard of living. Wherever individuals and families are living across the country, if they cannot afford the cost of this basket of goods and services in their particular community, they will be considered to be living below Canada’s Official Poverty Line.

By participating in this consultation, you will be supporting Statistics Canada’s ability to accurately measure low income and poverty.”

In other words, the frontier of poverty is officially tied to the MBM threshold and then the public is consulted to assess whether it’s indeed the case!?

At lot of assumptions are made here through the association between what is meant by basic needs coverage, a modest standard of living (not defined by Statistics Canada[4]) and an official poverty line. What about the respective position of these concepts “within a field of possible thresholds” (CÉPE’s 2009 advice, page 34) in the continuum between poverty and non-poverty? More confusion is added in the questionnaire, where the MBM basket is presented as follows:

“The basket includes items such as healthy food, appropriate shelter and home maintenance, and clothing and transportation.

The items in the basket reflect prices in communities across Canada. […]

By selecting your province, city and family size, you can find out how much your family would need to stay out of poverty. Please tell us if you think these amounts are too high, too low or “about right”.”

Then people are asked to evaluate specific amounts for the basket’s various components.

This seems like a departure from the usual rigour of Statistics Canada, which is not known to have ever broken down the MBM thresholds into specific amounts for the basket’s components for other households’ sizes than the two adults and two children reference family. And there is good reason for this.

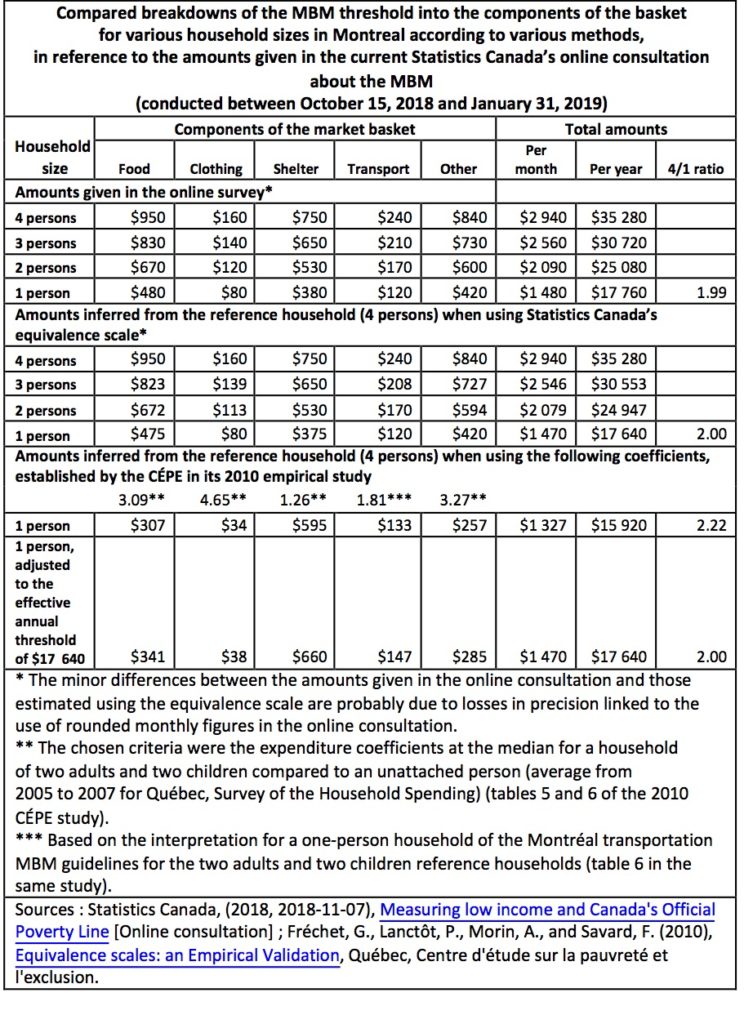

In a 2010 empirical study, the CÉPE showed that although it seemed to work for the total content of the basket (i.e., the total MBM threshold), the equivalence scale used to establish corresponding thresholds for other family sizes (the square root of households size) did not accurately represent the breakdown of expenditures for the specific sections of the basket (food, clothing, shelter, transportation, other necessities), at least for one-person households.

For example, the equivalence scale implies that to establish the cost of a basic standard for a single person, one must divide the cost of the basket for a household of four persons by two (the square root of four). However, in practice, the comparable cost of food or housing for a single-person household will not be half of what it is for a family of four. Most likely, it will amount to less than that for food and more, even much more, for housing.

Yet the online consultation (as well as the federal strategy, on pages 69-70) simply uses the equivalence scale ratios to establish the cost of the basket components proposed for evaluation to respondents of various household sizes. The result is that the amounts are broken down in ways that don’t make sense, as shown in the inset.

Unrealistic apportioning of the MBM components in the online consultationThe first part of the table below presents amounts found in Statistics Canada’s online consultation for households of different sizes in Montréal, and calculates their monthly and annuals totals, which are not mentioned in the consultation. The second part of the table shows that the amounts provided in the online consultation for each component of the basket closely match those obtained with the usual equivalence scale. The third part of the table uses the coefficients observed by the CÉPE in its 2010 empirical estimation of equivalent expenditure levels between a household of two adults and two children and a single person household. It also adjusts the results to the annual MBM threshold that can be inferred from the consultation for this household. Even though the CÉPE’s coefficients are somewhat dated, they reflect the distribution of expenses as it was actually observed in Québec at the time, which is useful for illustrative purposes (and calls for further research and updated observations for various household sizes). Indeed, it seems reasonable to suppose that where a Montreal family of four will spend $950 monthly for food, a person living alone is likely to spend closer to three times less (around $307 to $341, which is in line with a $315 recent estimate from Montreal Diet Dispensary), than two times less (480 $) as indicated in the consultation. Likewise, where this family of four will spend $750 for housing, an amount of $595 to $660 will not appear excessive for a person living alone. This time, the amount of $380 indicated in the online consultation is much too low. |

What kind of results can be expected from such a consultation if the indicated amounts for the key items in the basket are misleading?

A few pathways forward regardless

Slow and steady wins the race, says the fable. While the political will to reduce poverty is much needed and welcome in Canada, it would be regrettable to lose its potential due to a lack of reliable and credible foundations of its chosen poverty measure.

The MBM is a useful cost-based measure of basic living standards, but it needs proper care and assessment as an indicator within the broader concept of poverty. Choosing it as the official poverty line in Canada without such nuances compromises this proper use.

While consultations about the contents of the MBM are advisable, as we can expect that standards of living change over time, these consultations must be done in a manner that’s orderly and pays attention to the current state of knowledge without skipping a step between what is known and what has to be assessed.

What can be done in the meantime, if the federal government’s intent to reduce poverty is serious?

Here are some suggestions.

- Consider the MBM as a good indicator among a larger set of reliable low income lines and characterize the existing or considered lines in this set in relation to what they specifically reveal about diverse experiences of income poverty across Canada.

- Modify Bill C-87 accordingly and characterize the MBM differently than as the official poverty line in Canada, e.g. as an official line to follow the experience of poverty from the angle of basic needs coverage, as is done in Québec.

- Maintain the announced targets for the reduction of low income rates in reference to the MBM for what it is, without linking this line to the difference between being poor or not, and consider alternative measures and targets that could be used to assess and reduce the number of people living in poverty.

- Implement the announced National Advisory Council on Poverty, with a guaranteed independence in its mandate and entitlements, and a sound representation of rights-based advocacy groups and networks, including persons with a lived experience of poverty.

- Work closely with this Council in order to develop a plan with concrete policy measures, which are lacking in the strategy, so that these targets can be achieved.

- Maintain a distinction between having the resources to cover one’s basic needs, as monitored by the MBM, and being free from poverty as broadly defined in the national strategy to include the resources, means, choices and power necessary to acquire and maintain a basic level of living standards and to facilitate integration and participation in society.

- Expand the definition of poverty and its interpretation in reference to the rights mentioned in the definition of poverty given by the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

- Request Statistics Canada, in reference to the statement published in 1997 by its chief statistician of the time, Ivan P. Fellegi, to investigate what type of income indicator could correspond more fully to a poverty line along this broader definition, with respect notably to what has been published in Canada around the concepts of living wage and living income.

- Continue the ongoing revision of the MBM by Statistics Canada and ensure a sound maintenance of the surveys needed for its calculation.

- Temporarily put on hold the items of the online consultation about the MBM which are related to the cost of its various components for household sizes other than the 4 persons reference household, undertake the studies needed to establish realistic coefficients for breaking down expenditures in the sections of the basket of goods and services according to the size of households (in line with the 2010 CÉPE study), and start over with this aspect of the consultation.

- Observe where all households are situated, below and above the MBM threshold, or any other line used to characterize the experiences of poverty, so that envisioned actions for poverty reduction can be linked to the continuum of existing inequalities in living standards and incomes and to the changes needed more broadly in social, fiscal and economic policy to reduce these inequalities.

- Acknowledge that this also requires the elimination of structural and systemic barriers, including discrimination, and calls for a variety of income and non-income inequality indicators in the strategy’s dashboard.

There is still time to address these concerns and move the process in the direction needed to produce lasting and desirable results for all Canadians. Let’s hope the federal government listens and understands what is at stake, and then makes the necessary adjustments to get this right. It will be well worth the trouble for what comes next.

[1] An English version of the adopted act, without the enforcement notifications, can be found here.

[2] “For the purposes of this Act, “poverty” means the condition of a human being who is deprived of the resources, means, choices and power necessary to acquire and maintain economic self-sufficiency or to facilitate integration and participation in society” (Québec Act, article 2, French formulation here).

[3] “Poverty is: The condition of a person who is deprived of the resources, means, choices and power necessary to acquire and maintain a basic level of living standards and to facilitate integration and participation in society.” (Opportunity for all, page 7, French formulation here, same page).

[4] Other Statistics Canada’s publications present the MBM basket as “representing a modest, basic standard of living” in English, and “correspondant à un niveau de vie de base” in French.

Vivian Labrie is an independent researcher, associated to the Institut de recherche et d’informations socioéconomiques (IRIS). She has been involved in various ways since 1997 in the actions that led to the adoption in 2002 of the Act to Combat Poverty and Social Exclusion by the Québec National Assembly, and in the follow up of its implementation afterwards.

—

This article is a slightly updated English version of the blog post “Une consultation en ligne sur la MPC à recalibrer”, which was originally published on the IRIS website on October 17, 2018.

Interesting commentary. Overlaps with concerns I and others share.

https://coaottawa.ca/wp-content/uploads/documents/Submission-on-Bill-C-87-PH-final-11DEC18.pdf

For me, the simplest explanation to the public is to say that although footwear is canvassed in detail along with foodstuffs and clothing (although not toque in the winter), there are curiously no standards for shelter, no list, no standards. With equivalencies, people in poverty must live in hovels according to the MBM standard. Do they have heat? is the accommodation legal? Do they have access to census questionnaires? Can they file their taxes without threat of eviction? Can they cook? The answer is uniformly ‘no’ yet non-existent rents will still define a poverty standard in the MBM if we allow it.

The Liberal government is passing a bill, not to eradicate poverty robustly but to monitor it, set up an advisory committee, and cautiously support continued efforts towards a 2030 target reduction. As we have discovered with climate change, aspirational targets may well be missed when subordinate to politically more pressing day-to-day claims.

The problem for Liberals is that effective poverty elimination would require changes to trade, labour, and fiscal policies that currently favour the well-off. Rather than challenge powerful elites, better for Liberals to travel “a long road” that allows business as usual, yet radiates warmth from the ritual exorcism of poverty.

Footnotes:

1. L. Randall Wray, Professor of Economics at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, Research Director with the Center for Full Employment and Price Stability and Senior Research Scholar at The Levy Economics Institute http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2014/04/mmt-policy.html

“Well it’s very easy to reduce the inequality that results from low income, from poverty, from low wages; all you have to do is offer jobs. Minsky did a calculation [in] 1974 and Professor Kelton and I did one around 2000. We showed that if you just give a job to anyone who wants to work you will eliminate two thirds of all poverty, even if you pay only the minimum wage. We would like to see the job pay more than that, but even at a minimum wage you eliminate two-thirds of all poverty. So most poverty is due to joblessness. People who cannot get jobs or maybe they get jobs that last a few months and then they are unemployed again. We need permanent jobs that pay a decent wage and you’ll eliminate most poverty. You’ll still need some kinds of anti-poverty programs but the jobs are the best anti-poverty programs there are, then you need something else to fill the gaps.”

2. William Mitchell, Professor in Economics, Director of the Centre of Full Employment and Equity (CofFEE), University of Newcastle, Australia

Anti-Poverty Week – best solution is job creation

“I have been to many meeting where policy makers, usually very well adorned in the latest clothing, plenty of nice watches and rings, and all the latest gadgets (phones, tablets etc), wax lyrical about how complex the poverty problem is. I usually respond at some point (trying my hardest to disguise disdain) by suggesting the problem is relatively simple. The federal government can always create enough work any time it chooses at a decent wage to ensure that no-one needs to live below the poverty line. Read: always! It can also always pay those who cannot work for whatever reason an adequate pension. Read: always. If we run out of real resources which prevent those nominal payments (wage and pensions) translating into an adequate standard of living, then the government can always redistribute the real resources by increasing taxes……

***

There is nothing complex about announcing that the government will pay a living wage to anyone who wants to work – just turn up tomorrow and the wage begins. If that announcement was made then we would know who wants to work for a wage and those who do not. For Anti-Poverty Week – the best thing the government can do is announce the unconditional job offer.”

3. The Social Enterprise Sector Model for a Job Guarantee

“Imagine 25 million people with no income or precarious forms of income. Now imagine 25 million with a decent base wage. The effect on the private for-profit sector would surely be more stable demand, ringing cash registers, increasing profits, growth and, yes, a lot more better-paying private sector jobs.

***

The experience of the New Deal and Argentina’s Plan Jefes shows that such programs can be up and running in 4 to 6 months and useful tasks can be performed even by the least skilled and least educated citizens.”