It’s Not What You’ve Got, It’s What You Do With It

I recently had the joy of spending a couple of weeks in Kerala, the little socialist state at the bottom tip of India. Apart from exquisite food, friendly people, beautiful jungles, and welcoming climate, Kerala’s greatest asset of course is its astonishing record in producing a literate, healthy, politically engaged society — all on the strength of a very modest GDP.

I am not in the camp of those who claim that GDP doesn’t matter, or that “growth” is somehow the enemy. Economic development very much requires being able to produce more useful goods and services (more value, not more flat screen TVs and Hummers). And of course, we must tailor our output to respect the environmental constraints around us; that doesn’t mean “doing less,” it means doing different things.

But what you do with your GDP matters just as much as how much of it you produce. And the “Kerala model” (as it is known in the development literature) shows very much that pro-actively shaping the nature of growth (massively priveleging things that make human beings directly better off) is essential to human progress.

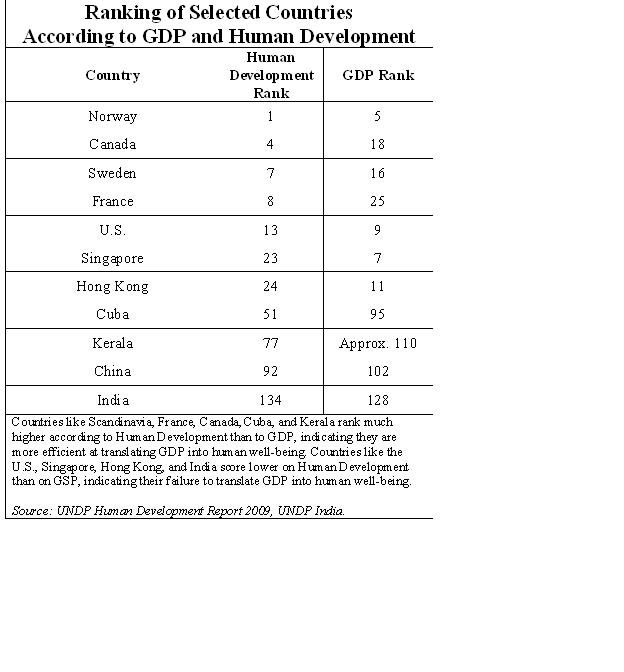

Below is my column on Kerala which ran in the Globe (complete with a sex joke at the beginning!). I got a lot of reaction, much from Indian expats who seemed glad just to have something decent reported about their homeland. Also, I’ve added a table comparing GDP and HDI rankings. There’s a correlation between GDP and HDI (which is why it’s totally wrong to say that GDP doesn’t matter). But there’s huge variation around that correlation, too (with Kerala and Cuba being two of the outliers), indicating that the sex threapist’s advice is very relevant indeed.

A couple more tidbits on Kerala before I get to the column: this was not the first place in the world where Communists came to power via the ballot box. But I think it’s the first place they weren’t then forcibly removed. That wasn’t for lack of trying: Jawalharu Nehru (to his discredit) actually used emergency powers to eject the first Communist government from office in 1959 — after setting the stage with some of the same destabilization tactics used by the CIA in Chile in 1973. But the Communists, after regrouping, were able to win back office after a few years, and they’ve been in office (alone or in coalition) pretty much ever since. Their emphasis on social development, plus their reputation as the most transparent and least corrupt state government in India, has maintained their popular support.

The current economic policy is a very intersting amalgam of efforts to entice private investment, combined with a still-diverse state-owned production sector (including everything from cashews to hotels to a new plant building railway cars), combined with support for almost pre-capitalist small-scale production in workshops and farms. Massive supports for farm communities (including labour laws which prohibit the worst kinds of rural servitude common elsewhere in India) have been the most important reason for Kerala’s low poverty rate.

OK here’s the column now…

There’s More to Life Than GDP

Any good sex therapist will tell you: it’s not what you’ve got that matters. It’s more important how you use what you’ve got.

The same sound advice applies in the economy, too – not just the bedroom. Statisticians and politicians alike obsess over the latest ups and downs of GDP, assumed to reflect the progress of the whole economy. But in practice, a large GDP means nothing, if it isn’t put to good work. If extra economic production (measured by an expanding GDP) does not result in improvements in the human condition, then what’s the point?

In sum, it’s not enough to stimulate more growth (GDP, production, work). Economic policy must be just as concerned with ensuring that the fruits of that growth are used efficiently, to improve the lives of the people who produced it.

An outstanding example of this maxim in practice is provided by the economic and social experience of Kerala, a state on the southern tip of India. Kerala has the same population as Canada, but crammed into an area smaller than Nova Scotia. Apart from the crowds, however, Kerala’s most unique feature is how it has leveraged its limited GDP to achieve remarkably strong outcomes in health, education, and quality of life.

Kerala’s literacy is the highest in India, well above 90 percent. Infant mortality is the lowest. Thanks to grass-roots education programs and economic opportunity for women, Kerala’s birth rate is one quarter of that in the rest of India – lower, even, than in the U.S. By these social indicators, then, Kerala could even be considered a “developed” economy, despite its Third World levels of output. On my own recent travels through Kerala, I witnessed almost none of the grinding, desperate poverty commonly encountered in most of India.

A stark statistical indicator of Kerala’s social success is provided by the United Nations’ ranking of countries according to its Human Development Index (HDI). India as a whole performs miserably in this ranking. In fact, in recent years it has slipped even further down the list (from 126th in 2006 to 134th today), despite its free-market economic boom. Shockingly, even as India’s expansion was praised by everyone from business analysts to our own dancing Prime Minister, the relative well-being of Indians was actually declining. Steel tycoons, call-centre entrepreneurs, and Bollywood producers are certainly loving it; in 2008, India’s 53 billionaires possessed combined wealth equal to one quarter of the annual output produced by the whole country’s 1.2 billion people. But the U.N. data confirms that Indians, on the whole, are not benefiting nearly enough.

Kerala’s GDP per capita is decent, but not spectacular, by Indian standards. But its superior education and health outcomes push it well up the human development ranking. It boasts the highest HDI of any Indian state. And if it were a country, Kerala would rank 77th in the world – ahead of countries (like Turkey, South Africa, or Peru) with much higher GDP per capita.

Kerala’s unique approach reflects its fascinating political culture. For most of the last half-century, it has been governed by elected Communists (either alone or in coalition with other left parties). Economically, the government has priorized public services, small scale co-ops, and rural land reform, instead of chasing call centres and outsourced jobs from Western offices. Productivity in some of Kerala’s smaller workshops is pre-industrial – but that’s better than doing nothing, which is the fate of tens of millions of dispossessed workers elsewhere in India. Kerala’s government has strongly resisted the corporatization of agriculture, and this has helped it achieve the lowest rural poverty in India. Again, the contrast with the rest of the country (200,000 desperate Indian farmers committed suicide in the last decade) is jarring.

Kerala’s investments in its people, perhaps ironically, have made its people one of the state’s most lucrative exports: some 2 million Keralans work in the Persian Gulf countries (usually as doctors, nurses, and engineers), sending back billions each year in remittances.

Yet there is also a growing high-tech sector at home, centred around a 25,000-strong Technopark in the state capital. The complex is owned by the state government, but operated in partnership with global IT corporations. This funny coexistence of capitalism and socialism is called “flexible communism” by the locals.

Business owners bemoan the hassle and lost productivity resulting from the strikes and protests that are a regular feature of daily life in highly politicized Kerala. On the other hand, it’s precisely because they feel empowered to fight for their interests, that Keralans have managed to win the highest standard of living in this vast, diverse country. Other parts of India lose very little worktime to strikes – yet their people are demonstrably worse off.

Perhaps that’s a lesson for all of us. Higher GDP doesn’t automatically translate into human prosperity. We have to stand up and make it happen.

That is amazing and inspiring.

Unfortunately, Harper’s economics “nolidge” is not people-oriented. In a couple of years, if the reign of Stevie the Spiteful continues, Canada will no longer be in the same category as the Scandinavian countries, France, Cuba or Kerala.

Jimbo I can see you have a future as a foreign corespondent, but do not forget to give us some food talk, along with the sex .

How much does exchange rate variation count in calculating the GDP rankings? It is purchasing power parity I presume. Presumably you have given us figures in $U.S. Would this change using SDRs I wonder?

It is amazing what the left can achieve for human progress when it has grass roots organizations which have resources and organizational capacities that are not merely party cadres or top down bureaucratic creations. It also has the benefit of keeping the respectable leadership accountable: that is in constant state of negotiation with the people it represents.

Travis is bang on that’s it’s all about participation and accountability at the grass-roots level. Kerala has this amazing network of NGOs, community associations, campaigns, unions, and other organizations that actively engage in political discussions and promote the interests of their constituencies. It makes for an informed, enlightened, active citizenry — and helps to keep the government’s eyes on the prize.

I suppose something like that is what Chavez & Co are trying to build in Venezuela (and parallel efforts in other Latin American countries, like Bolivia). If they can do it, then I predict they will win.

Duncan, PPP has a lot to do with those numbers in the tables. That’s what explains how they can rank Singapore and Hong Kong above Canada in GDP per capita (a fact I don’t believe for a minute). The same methodology used to put Ireland at the top of the GDP tables — which was equally ludicrous. I think there’s a lot of misunderstanding about how international GDP comparisons are calculated.

It helps left leaders not only to have demands emanating from the grass roots but it also helps them to have a credible threat when negotiating with their conservative counterparts.