Why Deleveraging Hurts So Much

Last Friday I had the honour of sharing the podium (and a good supper afterward) with Steve Keen, the awesome Australian economist who was recently named the winner of the “Revere Award” for most accurately forewarning of the global financial crisis. In fact, that award was announced the same day we spoke together to the Politics in the Pub speaker’s series in Sydney. Here are links to the Revere Award announcement (from the prize sponsors, the Real World Economics Review), and to a report and film clips (by Steve, on his Debtwatch blog site) of the night’s activities:

http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/2010/05/15/stanford-and-keen-double-bill/

In his closing remarks to the group, Steve Keen walked through a very interesting arithmetic exercise to reveal the importance of new credit creation to overall aggregate demand conditions (and hence, in a demand-constrained real world, to growth and employment). The simulation was largely lost on the crowd (which had imbibed heartily throughout the proceedings – that being the whole point of “Politics in the Pub”). But it did spark my interest in following up. (For Steve’s original math, check his Debtwatch bulletin #43, at the same blog site noted above.)

Here I recreate, with full credit and thanks to Steve Keen, the logic of his argument, utilizing Canadian data. The implication of Keen’s model is that the only reason the recession was not much worse in Canada (like Australia) is because of the surprising continued expansion of private indebtedness right through the downturn. In both countries, this was entirely due to feverish activity in real estate markets (mostly the resale of properties, not new construction), sparked by near-zero interest rates and a healthy does of speculative greed. That expansion of private debt, despite declining incomes, has pushed private debt ratios to record highs. Clearly it cannot continue forever (although it’s not easy to predict exactly when it will turn around).

But the implication of Keen’s analysis is that when the expansion of the private debt burden does stop (as it must sometime), it will wreak disastrous results on spending power, GDP, and labour markets. It’s not just that a decline in debt would be associated with another downturn; that’s something most of us are well aware of. Because our economy has become so dependent in recent years on the rapid (and obviously unsustainable) expansion of private debt, merely stopping (or substantially slowing) the growth of that debt would knock a giant hole in aggregate spending – enough to send us into a double dip.

Here’s the logic, illustrated by two tables posted below.

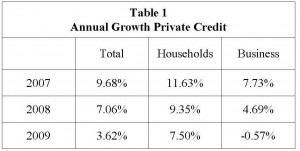

First, keep in mind that total aggregate demand (or spending power) equals the incomes generated by real economic activity (ie. GDP), plus net new borrowing. Table 1 shows that Canada’s private sector was borrowing heavily in the years leading into the crisis. At peak in 2007 (the last full year before the crisis hit), private debt expanded nearly 10%, with households leading the way but businesses close behind. As the recession took hold, business borrowing slowed to a standstill. But after barely catching a breath in fall 2008 (after the shock of Lehman Bros.), Canadian households kept on borrowing like there was no tomorrow, lured by the interest rate cuts. Housing prices, which had earlier started to turn down, promptly took off. The resulting real estate boom (so far reflected much more in agents’ commissions, not new home construction) has been a key source of the modest GDP growth generated since the recession’s trough a year ago. The business sector, in contrast, does not share households’ optimism (perhaps a better word is “complacency”?): business credit has not budged since November 2008.

All that new borrowing (driven solely by households) adds to the ability of Canadians to spend on real output, imports, and assets (including real estate). The relationship between this total purchasing power (aggregate demand) and actual production depends on whether total demand is growing, and on how it is divided between production and assets.

Keen’s point is that the rise in private debt provided an increasing share of total spending power in the years leading up to the crisis – one of the reasons he knew that boom couldn’t last. Moreover, as debt becomes large relative to GDP, then those increases in debt become ever more important in order to sustain total aggregate demand (GDP plus new debt) and prevent a downturn in spending (which would be reflected in a combination of real recession, disinflation, and asset price deflation).

See Table 2 for an application of this model to the Canadian data. In 2007, private debt grew (line 6 of Table 2) by over $200 billion (almost 10%), and this new debt accounted for 12% of aggregate demand that year (line 8). With all that spending power, the economy grew rapidly. As the economy slipped into recession, private debt growth slowed (and became 100% dependent on Canadian households being willing to keep pumping up those debt ratios). For last year as a whole, private debt grew by half as much (under $100 billion), and accounted for half as large a share of GDP (6%). The mere slowdown in private debt creation accounted for about half of the drop off in total private aggregate demand last year (which declined by almost $150 billion). Continued private debt creation (again, 100% from households, none from businesses) combined with falling real incomes pushed the aggregate private sector debt burden to an all-time record of 170% of GDP (line 10 of Table 2).

(Just for perspective, remember that the federal government’s debt burden amounts to less than 35% of GDP. Why does public debt attract so much attention and panic … while the far larger, and I would argue more dangerous, accumulation of private debt, is mostly ignored??? This reflects the Animal Farm-like mentality of most politicians and commentators: “Private debt good, public debt bad.”)

The dramatic actions of government partly offset this steep drop in private sector aggregate demand. Almost $80 billion in new borrowing by governments at all levels (line 11 of Table 2) offset over half of the decline in total aggregate demand that otherwise would have occurred. In other words, by this reckoning, the recession would have been twice as bad without those government deficits. Keep that in mind as the balanced-budget fanatics now aim their cannons at your favourite social program.

Now, let’s try to extrapolate this analysis into the future. The last three columns of Table 2 do that, utilizing a starting point for nominal GDP of $1.6 trillion – roughly where it will be by the midpoint of 2010. (We are thus looking one year forward from now, rather than thinking in calendar years.)

Consider the problem facing the Canadian economy, as it tries to wean itself from the debt that has fuelled its recent progress. It is very hard to fathom that Canadian households are going to keep borrowing at their current drunken pace, for several reasons:

- interest rates can only go up;

- overblown real estate prices will almost certainly retreat over the next year, cutting into demand for two reasons: less credit is required to buy cheaper houses, and (more importantly) a decline in prices immediately throws the speculative engine that has driven recent sales into reverse;

- the rising debt burden of consumers would eventually curtail new borrowing even without those factors.

I present three scenarios in Table 2: new private debt slows down (to half of last year’s net borrowing), private debt stabilizes (no net new borrowing), and the private sector actually starts to deleverage (something that’s been warned about but hasn’t actually started to happen yet). In the first two scenarios, new borrowing adds little or nothing to aggregate demand; in the last scenario, it takes away from aggregate demand. Line 10 of Table 2 indicates that none of these scenarios would lead to a dramatic decline in the already-bloated private debt burden: it falls by a few points in each scenario from its current record level, but even in the deleveraging scenario only falls back to where it was in 2008. (Just imagine if private agents actually followed the same debt-phobic thinking of current politicians, and tried to significantly reduce their debt burdens; as my friend Doug Henwood puts it, we’ll all be wearing barrels.)

At the same time, of course, governments at all levels are now trying frantically to slash their own deficits (which were so important to limiting last year’s downturn). Let’s assume that they succeed (despite swimming against the macroeconomic tides) in reducing their collective deficit by half moving forward.

The bottom line result is shown in Line 13. In the debt slowdown case, total aggregate demand grows by 4 percent in nominal terms compared to 2009 year averages. After deducting inflation, that’s consistent with very slow growth (1-2%) in the real economy – not enough to put a dent in our unemployment. In the debt freeze case, nominal aggregate demand grows by only 1% – which implies outright contraction of the real economy, and rising unemployment. Even a modest deleveraging by the private sector leads to a significant contraction in nominal demand, and a very severe (depression-style) contraction in real output and employment.

The arithmetic insight here is that it doesn’t take an actual contraction in debt to bring about a real recession. Just slowing or stopping new debt creation will do the trick – because our economy has become structurally dependent on a continuing “fix” of debt to pay for the stuff we produce.

Second, to the extent that Canada is experiencing a recovery (and I am still not convinced that is an appropriate use of the term), it has been 100% dependent on the willingness of Canadian households to pump their indebtedness to record levels. (According to Statistics Canada, household debt was already 144% of disposable income at the end of 2009.) Once that willingness to go into hock reaches its inevitable limit, then there is nothing else pulling up the slack. In particular, the vaunted Canadian business sector has done nothing so far to fill the demand gap in our economy; all the recovery so far (such as it’s been) has been courtesy of households and governments.

Thirdly, the efforts by Canadian governments to slash their deficits in coming years would make a bad situation far worse, if in fact private debt slows, stops, or (god help us) reverses.

I am not predicting a debt collapse here. I am simply highlighting how fragile the base for Canada’s continued expansion has become – and how withdrawing the only sources of recent spending (household and government debt) would put us quickly right back into the soup again.

My acknowledgements again to Steve Keen for his insights. Here are the tables:

just a small point Jim,

It is not consumers to blame for household debt reaching 144% of disposable income, it is in part due to bankers continually providing the credit and secondly the stagnation of wages over the past many years.

As you so rightly point out, we are potentially just caught up in a different phase of this debt cycle contra the US and our debt ravaged consumption burst draws nigh. It has been very mechanistically orchestrated, as long as the household shows some ability to pay, the money is lent and spent. It would be a fascinating study to venture onto the shop floor of a money lending institution in Canada and spend the day lending.

I wonder how I would feel at the end of the day- perplexed I am sure and potentially a little more anxious than usual.

Great piece. I was just reading about exploding household debt in the local paper yesterday. I notice housing sales in Canada and slowing – could the end be right around the corner?

Hey Jim,

This is a great piece. I’m wondering how this analysis jives with the Godley-eque framework the Wenonah did for us:

http://www.progressive-economics.ca/2008/03/17/some-inconvenient-accounting-and-the-fall-2008-fiscal-update/

http://www.progressive-economics.ca/wp-content/uploads/2008/03/picture-3-gif.gif

In that picture, in 2007, net borrowing from households offset net saving from corporations, but in numbers smaller than your private debt growth, while government surplus was equivalent to surplus on international transactions. Perhaps this just reflects flows of funds within sectors and not the aggregate impact of new credit — can you clarify?

Also, do international transactions fit into your picture? For example, a surge in exports might offset some of the negative impact of deleveraging (at least for Alberta!).

Not to belittle the problem of the consumer debt increase, which is very real, but when the bubble does burst, slowly or quickly, the usual people will then castigate the middle and lower classes as being to blame.

But in fact the most powerful educational media of all are quite intentionally using propaganda to increase that debt for their own profits. Every day and all day we are bombarded with cleverly designed and executed messages to tell us to spend more, which of course requires borrowing more, because they are not paying us more.

So we get people to believe that they need more, they deserve more, and “you know you want it”, and “you deserve the best”, and all that, and when it all goes bust we will blame the victims as usual.

We should know better – we do know better – but billions and billions are being spent to convince us that we should do foolish things which, if we succumb to the incessant messages (and we do, we do) we will be told that the inevitable result is really all our fault.

And most of us will probably believe it.

Good analysis. We should also note that a large part of the 2009 federal budget was aimed at keeping the real estate and construction markets rising by and encouraging more of this leverage through the renovation tax credit, first time homeowners plan etc.

With many of these incentives coming to an end and interest rates rising we will be belatedly dealing with the private sector deleveraging that other countries are already going through. That’s why Carney and some bank economists are becoming increasingly vocal about the need for business to start investing more (particulalry since their balance sheets are really quite good).

Another Revere Award finalist, Dean Baker, was of course very prominent in warning about the real estate bust in the US. He did some good analysis about what impact lower house prices could have on GDP through the wealth effect. I applied that to Canada in September 2007 (Housing Bubbles and Busts in http://cupe.ca/updir/Economic_Climate_-_Sept_2007.pdf.

At that time I figured that a correction in house prices to more normal levels could lead to a reduction in GDP growth of 2-3 %. Thanks to ultra-low interest rates, we still haven’t had that correction. We’re in a tight situation. If there’s little real wage growth, but a substantial hike in interest rates and no significant demand coming from elsewhere, there’ll be a lot of economic damage.

http://www.rabble.ca/rabbletv/program-guide/2010/05/features/stanford-weeks-not-rex-financial-literacy-bankers

There is always something about a woman with a beard and mustache that one should pay attention to, truly there is. I wonder if this woman will make an appearance at the CEA?

As noted in comment the RWE blog, this analysis makes no sense.

Domestic demand for goods and services equals C+I+G

Domestic income is Y

The excess of domestic demand over domestic income is C+I+G-Y=M-X

Thus, the “change in debt” that is relevant to the real economy is the trade deficit– or the current account deficit if one takes a broader view of income.

I saw a great presentation by Steve in Dijon (France) in December. I felt at the time that he’d make a great PEF keynote speaker at next year’s CEA Meetings (June 2-5, 2011, University of Ottawa).

This hilarious video is quite an anti-dote to the ongoing indoctrination ‘How to have faith in Bankers and save the Civilisation’. If that was not enough our government is paying an organisation to troll online comments to correct what it calls ‘misinformation’

mattehttp://www.news1130.com/news/national/article/58287–harper-government-monitoring-online-chats-about-politics

Now the question is how will the Auditor General Sheila Fraser see this kind of government program’s in her performance audit. She was on ‘Power and Politics’ with Tom Clark this afternoon. I am not assuming the smile flickering on her lips was because she can taste the victory combing through MP’s expense accounts. I am not interested in who is going to come undone but rather who is going to come out smelling of roses.

My faith has been shattered too many times watching certain types come out arguably better placed, invariably happens to the likes of those from City of London corporation types or the Wall St.

Ms Fraser though can be relied on to make public her views and reports in a accountant like manner without the provocative or incendiary language. Considering that the Conservative government took to heart her findings on the Sponsorship scandal and bring it up at every opportunity whether it is relevant or not. In fact all the times I have watched the News/Question Period, I have not seen Mr Duceppe or his fellow MP’s bring it up. I can only conclude the anguish the Reform/Conservative Alliance feel for Quebec is greater.

The official website states that OAG is an independent and reliable source of the objective fact-based information for the Parliament. Not just for the government. Since Ms Fraser has served the Chretien and Martin governments in this position, so she is qualified to give Canadians the report on the how the present Harper governments much larger and exponentially budgeted PMO (apparently trying to mirror the White House model) compared to previous governments serving the Canadians better?

The Parliament should seek a Full Comprehensive Audit on this issue.

Good post.

Given the comments, it might be worth clarifying at some point the difference between net debt (which always total 0 if you cast the net wide enough, and don’t worry about the cut taken by the financial sector as middleman) and gross debt which can expand within sectors (i.e. the household sector could have net debt of 0, but still be in very dangerous economic territory due to the high level debt owed by some households to other households and could still have financed a lot of additional spending via that borrowing).

Thank you, Declan.

This is a great post. I would be interested in knowing what we should actually be doing now to mitigate the problem. In light of the governments policies towards the CMHC (promotion of sub-prime lending backed by taxpayers etc.) Canadian indebtedness has actually gotten a lot worse in just the last year and a half.

It appears that the market has already peaked indicating that harder times may be coming for commodity based economies like the Aussies and Canucks.