Balancing Budgets – What Harper Should Be Worried About Now

In the past few weeks some of Canada’s most respected economic authorities, including Bank of Canada Governor Mark Carney, have voiced concerns over the fragility of the recovery, globally and at home. Now Paul Krugman joins that chorus of Cassandras, pointing his finger straight at the wishful thinkers who say Canada’s heavy lifting is done when it comes to economic recovery.

If the Prime Minister and the Finance Minister know that it’s not time to start focusing on balancing the books, they’re not acting like it.

In the run-up to the G8/G20 in June and since, the Harper team’s message box has focused on cutting deficits and paying down debt. For months they have characterized these as the two leading public policy objectives for Canada and the rest of the developed world, less than two years after the broadest and most sudden economic crisis to rock the global system since the 1930s.

Indeed, just a few days ago Finance Minister Jim Flaherty bragged that Canada was punching above its weight, shaping the world’s response to the post-crisis world by scuttling global bank taxes; and leading by example, using the rebound in Canadian stock markets, GDP, exports and jobs to show the rest of the world how to launch a cobra-quick attack on deficits.

Today Paul Krugman weighed in. Speaking at a conference of lawyers, he reminded his audience that government balance sheets are only part of the problem going forward.

Household budgets are a bigger part of the economy, and re-balancing them will take a lot longer if governments prioritize putting their own fiscal house in order first. On this front, Krugman notes, Canadians have little reason to be sanguine about what happens next.

Though our labour market did not lose jobs for 27 long months as in the U.S., he reminds us we have one of the worst debt to income ratios in the world.

In fact Canadians have the worst debt to income ratio of 20 OECD nations.

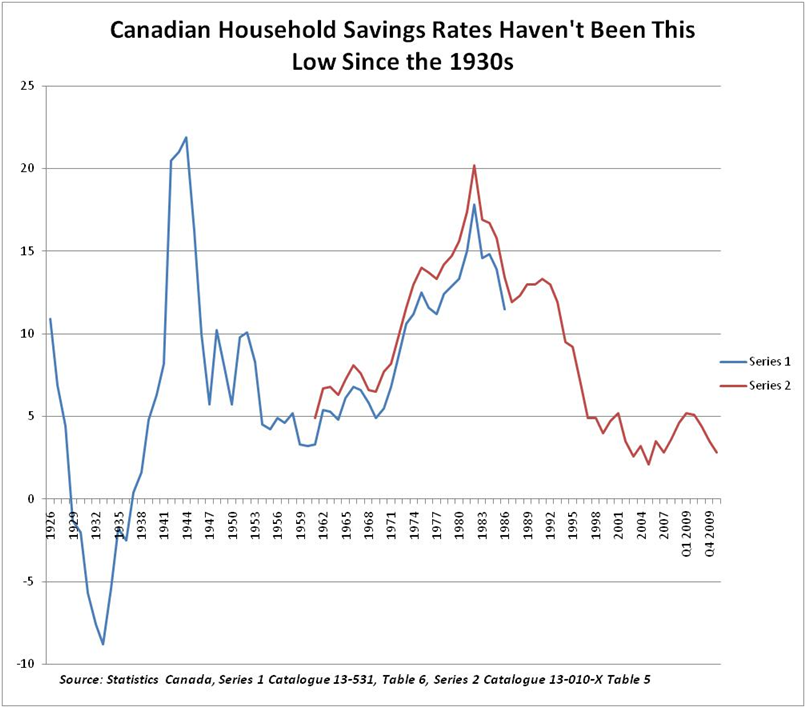

He went on to deliver this shocker: today Canada’s household savings rate ($2.80 on every $100 dollars of household income) is less than half that of the U.S. ($6.40 on every $100). He said that’s the first time this has occurred since the 1970s.

(As an aside, the Globe and Mail article on this topic did not cover this aspect of the speech. This is taken from the Toronto Star’s account.)

The message about how exposed Canadians are, and which balance sheets need to be balanced first, is one worth repeating. Indeed, we at the CCPA have been repeating it since last April, with the publication of Exposed: Revealing Truths About Canada’s Recession. By any historic standard, this is no routine recession.

Here’s a sobering factoid that takes Krugman’s shocking comparison even further: You actually have to go back to 1938 to see Canadian household savings rates this low.

In 1992 (where we are now in the cycle, two years after the economic crisis began) the national savings rate stood at 13%. At that time the Bank of Canada’s prime rate was 7.5%, the average 5-year mortgage commanded a 9.5% rate of interest, and a second decade of assault on middle class earnings was yet to begin in earnest.

That was then, this is now.

Interest rates are at historic lows, lower than even when the Bank of Canada was first put into place, in 1934. That means it is easier than ever to borrow and less attractive to save. But that ignores a bigger truth: it’s getting harder to save., and not just for the poorest among us.

Unremitting increases in the costs of housing, education and transportation while incomes are stagnant (or worse) means it may take a long time for savings rates to climb.

Rising debt levels since the crisis began is one obvious indication of how hard this is going to be: In the fall of 2008, before the crisis hit, Canadians owed $1.40 owed on every dollar of disposable income. That broke all previous records. At last count (1st quarter of 2010), the average Canadian household owed $1.47 on every dollar they took in.

Krugman reminds us of what we all know: interest rates have nowhere to go but up. Indeed, it’s a fine balancing act, leaving behind an era of easy money, and making ends meet.

Hope someone on Team Harper is listening.

As, increasingly, the mainstream economic indicators point to a coming second wave of “recession”, it begs a second look at the Federal government’s plan to eliminate the mandatory long form census.

I’m beginning to suspect that this initiative is really a intended as a major component in the Haper government’s fall-back plan should the national economy succumb to a second (and probably severe) recessionary tidal wave.

As others have duely pointed out, the resultant lack of pertinent social and economic data would make it very easy for the government to issue all manner of specious claims about the socio-economic well being of Canadians.

Equally, without a coordinated and reliable source of such information it becomes very difficult for any citizen, NGO or parliamentary opposition party to refute or dispute the truthfulness of such claims.

An improvished and emasculated StatsCan becomes an easy-to-manage outlet for all sorts of business-as-usual propaganda. As the economic status of Canadians worsens it will become increasingly important to have a PR program in-place to continue support for the neo-liberal agenda. For it’s own survival, it will imperitive for the Harper gorvernment to manage and contain public opinion. Perhaps StatsCan can then be re-branded as “StatScam”…

Regardless of motivated intent, the elimination of the census long-form is simply one more assault on the health of the democratic process in this country.

Over the past 4 or 5 years, Stephen Harper’s actions have clearly indicated that he is at best indifferent to real democracy and possibly even contemptuous of it. Democracy in Canada is to be democracy on his terms – heaven help us if he should ever claim a majority parliment.

“Interest rates need to be higher too, artificially low interest rate at 1% doesn’t allow canadians to save at a return. Saving is not just putting away a certain % of your paycheck, its about allowing the interest to accumulate.

When my grandmother was 19 she had 1000$(alot of money then) saved with 18.8 rate for 10,13 years before she saw a steady decline in rates in her lifetime from 20% rates to 1%. She is 83 and has the savings but if she was 19 again given todays rates she would have to invest in higher yielding stock to have the intrest she erned for retirement, there is a reason einstein said the greatest thing is compounding interest.

The relatively low rates can easily explain the dismal savings rate compared to our parents and their parents. Also compounding interest is why low rates are inneffective for the long term borrower. We should have higher rates to make it worth saving for ritirement. Our parents, & their parents who saved every penny did that under higher interest rates”

(November 26, 2009, 11:28 am, ps a little late on the Uptake are We?)

Had we kept the higher interest rates from 1992, there would not be as much of a reason to raise them as there is now.

1992, rates, led to more wise investment descisions, rather then the easy money “get quick rich schemes”, and investment in housing, low interest rates has created.

The biggest reason rates should have stayed high, is at least we would have savings to spend.

savings will never increase over the long term, say 5 years, without finiacial reward for doing so, and to think otherwise, is iresponsible.

Ill only spend, the interest on my savings.

my Grandma biggest contribution, her whole generations biggest contribution was the years they saved out of current income to spend at a later date in greater excess then otherwise possible, whiched helped create jobs etc.

Where are the savings going to come from this time to spend, to create infrastucture, companies, jobs etc, to pay taxes, like my grandmother and others, who used the interest from their savings to help build this country we live in…

“The relatively low rates can easily explain the dismal savings rate compared to our parents and their parents.”

Those rates have been low for a much shorter time than incomes (which have been declining for about 10 to 20 years) for most people. My parents (and likely yours) were also able to expect decent wages and job-stability; those two factors are pipe-dreams for too many workers now.

“The biggest reason rates should have stayed high, is at least we would have savings to spend.”

You realize that high rates would’ve also done much to help tank the economy when it went south, right? The vast majority of people are borrowers, not lenders. Crappy wages and high interest rates spell trouble for most people.

“her whole generations biggest contribution was the years they saved out of current income”

Maybe. But that was also a time when labour was _much_ more militant and, thanks to the bourgeois-created depression, were able to work with the more progressive wing of the bourgeois to ram home legislation that prevented people from starving in the streets (it also helped blunt a revolutionary edge, but that’s another point).

Excellent post! Ultimately debt is the contradiction of neoliberalism as a hegemonic accumulation strategy.

I would pick one quibble with your analysis though. The use of the term “middle class” is highly problematic in this case. Most classes of professionals and small business people (not petty proprietors) have done pretty well over the last 30 years. It has really been a war on the blue and pink collar contingent of the middle class. Perhaps we can call them the working class?

Well there is no question that there is a war on the working class, call them the middle class if you like. The rich are getting richer; and doing so on the backs of the poor. HST, sales taxes and so-forth hurt the poor far more than the rich, who have never paid their share of taxes. But the biggest problem with economics is that the underlying assumptions are wrong; and some very well respected economists are making them with great regularity. Recession? What recession? We have two important economic factors that have not been properly factored into the equation. Globilization and the Information/Techonology age. Globilization is about Capital Market Liberalization and that spells “corruption”; and the Information/Technolgy age spells “replacing workers with technolgy and capital” which equates to decling consumerism and unemployment, which starts an exponential increase in social assistance, and I might add, the health and social problems that burden society, and manifest as a consequence, are also not computed into the equation. But what do I know? I am anthropologist!