Luxury carbon

I was talking about carbon pricing and BC’s carbon tax recently and Michael Byers asked me about the prospects for a progressive carbon tax in terms of its rate structure. My first answer was that I liked the idea but was not sure how that could work in practice; that is, tax carbon and deal with inequality through the income tax system. It is not a great answer given that the highest-emitting households are also the richest, and therefore most easily able to absorb a carbon tax.

But my green jobs and sustainable production collaborator, Ken Carlaw, came to me with an alternative idea: why not have a different rate for especially GHG-intensive goods and services, many of which are consumed by the wealthy. I’m sure which one of us spat out the term “luxury carbon” but I think we are on to something here. And while many ordinary folks out there may not be keen about a carbon tax, they just might support a “luxury carbon tax” on jet-setters and any gratuitous combustion of fossil fuels. A big tax, like $200 per tonne, would be appropriate, and ideally it would be a national tax in order to compensate for border leakage.

Air travel would seem to be an obvious target for a luxury carbon tax, and business class would get dinged extra since those seats take up more space. I’d also lump in high-GHG vehicles like most SUVs. And in the gratuitous consumption category, we’d have to include all-terrain vehicles, dune buggies and snowmobiles, all of which are recreational vehicles that are annoying even if we don’t consider greenhouse gases by making everyone else around them worse off due to noise. And on the water, jet skis and yachts would be targets.

The tricky bit is that most of these just burn gasoline, so it would be difficult to apply a luxury carbon tax at the pump. It may need to be applied at the time of purchase or through annual license fees (hat tip to Seth Klein on this point). Outside of mobility, the tax regime would have to isolate specific goods and services for their GHG-intensity. Monster homes would seem straightforward, but other categories need some more thought.

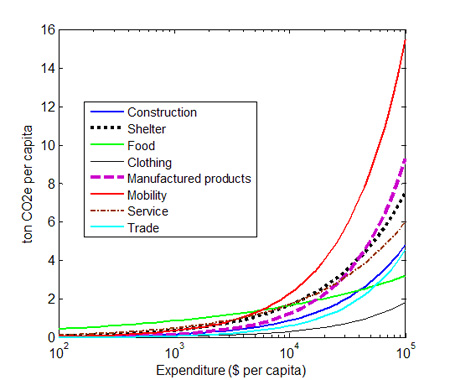

On a related note, here’s a graph from the Norwegian Institute for Science and Technology’s Carbon Footprint of Nations web site (they also have a really cool calculator of the carbon footprint of different nations; did I mention how much I love the Nordic countries?):

The log-scale of expenditure along the bottom may be a bit confusing the lay reader, but what it says is that carbon footprint really only takes off when per capita expenditures rise above $10,000, and by $100,000 they are truly astronomical. Mobility is the most noticeable of the categories, which concurs with general presumptions about a luxury carbon tax, but manufactured goods are also an interesting one. This analysis takes into account embedded carbon in imports (i.e. if a good is manufactured in China, standard accounting would attribute those emissions to China, not the country where consumption happens).

Nice post, good point. And this is why serious public transit has to get off the ground because one of the drivers of mobility is housing costs. That train running from mission to Vancouver needs to go three times a day and extend to Chilliwack for at least half the cost. And, here is the pony, it needs to be rapid rail.

A luxury carbon tax is fraught with complexities and unfairness that make cap and trade look simple. For example in the north all-terrain vehicles provide necessary transportation. Besides, the reductions produced would be tiny compared to what is needed. A broader program would be needed, anyway.

That chart is interesting, but people should keep in mind that almost everyone in Canada would be between the second or third dash after 10^4 and the end, where the chart it pretty linear.

Looking from the world perspective, a luxury carbon tax is easy. Just apply it to everyone in Canada and the other developed countries.

If fact, if then relationship between carbon emissions and expenditure was linear (as one might expect), putting it on an exponential scale like that would make it look exponential when it wasn’t.

Slate magazine recently started a series discussing this important issue.

When the Action Canada Network mounted a campaign against the GST (which turned so many Canadians into tax collectors as independent contractors) one thing that stuck out was that the power of the tax system to identify consumption “bads” was lost to the idea of preserving market “neutrality” an ideological construct if ever there was one. Instead of having one rate, why not have luxury rate, green rates, etc. Yes it would be require making some tough choices, but the current tax brings few benefits other than revenue.

Pricing is not the only way to ration things. It is the preferred way for market fundamentalists, but there are other options.

As long as the policy instrument is actual fact a retail sales tax — however named — the possibilities for variation depending on end use are a bit limited. For example, most speed boats take the same gas as the truck that’s pulling them. If there’s some notion of higher fuel taxes for jet aircraft, the international competitiveness considerations will limit any sub-national government’s ability to penalize ostentatious consumption.