Past peak oil, no emission reductions in sight

The International Energy Agency released its World Energy Outlook the other day, and made some headlines by calling 2006 the year of peak oil production. People have different perspectives on the topic of peak oil – many see it as the point upon which civilization as we know it will collapse; with my climate change hat on, I’ve generally thought of peak oil as a good thing that will finally drive us towards major investments in renewables.

But there is a catch: the peak refers to conventional oil sources, the proverbial gushers of old. As the Figure from the IEA shows in dark blue, this looks to be the case. And yet the good news I was looking for appears to have been disappeared. First, new supplies will come on tap, that we know about already (in grey) and the more speculative “we hope they are out there somewhere” kind (in light blue). Those fields will keep us level in terms of conventional supplies.

What is worse are the top two parts of the graph: unconventional supplies of oil (like the tar sands) and natural gas liquids, both of which are due to grow. The bottom line is that total output continues to grow, by close to 20% over current levels by 2035. This is really bad news on the climate change front, in total volume of emissions and because those unconventional sources are dirtier in emissions to get to market.

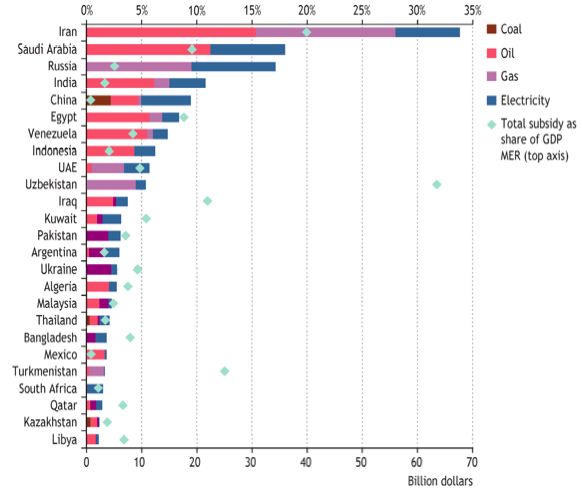

Supply is just one side of the coin, of course. Growing demand from China and elsewhere will undoubtedly drive up prices, and that may spur some transition to renewables. And perversely, global demand is being stoked by a number of oil-producing countries that subsidize fossil fuels for domestic use – a carbon tax in reverse. The IEA put these consumption subsidies at $312 billion in 2009.

James Hansen – who has a better grasp of the scale of the climate crisis than just about anyone – recently said the following in a lecture in Tokyo:

“In order to stop growth of atmospheric CO2 and return to a level below 350ppm, we must phase out coal emissions rapidly and leave most of the “other” fossil fuels [his accompanying barchart separates these from conventional gas, oil and coal], the unconventional fuels such as tar sands, in the ground. In that case atmospheric CO2 could peak at a value between 400 and 425ppm, depending upon how much of the remaining oil and gas we exploit.” [He then talks about how to get back down below 350ppm from there.]

With his next slide he reiterated the point – quick coal phase-out, no unconventional fossil fuels, don’t pursue last drops of oil – and concludes: “In other words, we must move on to the clean energy future now, rather than using all the remaining fossil fuels”.

If we don’t find a way to address this urgently, then most of the other issues dealt with on this blog will pale into insignificance.

We aren’t going to. Unless the system as it stands collapses, there will be no early transition, except maybe in Scandinavia and Germany. There is only one hope short of such a collapse: The price of renewables is gradually dropping as existing technologies are refined and new ones brought from the lab to production, such as various kinds of thin-film photovoltaics and so forth. Meanwhile, most of the yet-to-be-developed and yet-to-be-found oil fields are expensive to develop–deep sea fields and whatnot.

If and when renewables become clearly cheaper than oil, we’ll stop chasing the oil. Not before.

I do have a feeling from my readings that the chart above overestimates the yet-to-be-developed and yet-to-be-found conventional crude. Certainly new fields will be developed and others will be found, but my understanding is that peak oil theorists project decline, initially gradual but steepening, even taking such new developments into account. I think the IEA likely to be optimistic in its forecasting.

I’d like to clarify when I say “we aren’t going to”. The pattern I’ve been seeing over the past several years when it comes to geopolitical reaction to shocks to the system is this: When a major issue is first made clear (climate change, financial crisis) world leaders official and unofficial become flustered, scared. During this time they may worry so much about whatever crisis has come up that they allow movement towards useful solutions. Thus, when global warming first became a major issue we got Kyoto. When the mortgage/financial crisis first broke we got Keynesianism of a sort, gestures towards tough regulation, even a couple of things that looked oddly like nationalization of banks.

But then after the power brokers get used to whatever it is, normal reflexes set in, which is to say defense of the status quo at all costs and taking advantage of the crisis to pursue class warfare–Naomi Klein’s “shock doctrine”. We’re well into that phase on global warming; the window of opportunity during which authorities were flustered enough to allow the notion of serious solutions is long gone.

Purple –

Unfortunately, your “one hope” has a number of logistical obstacles too. The principal use of oil nowadays is as a motor fuel – comparatively very little is used for electricity or heating. So if we are to succeed in substituting oil we need either vehicles which run on renewables or vehicles which run on electricity. The first option is not possible on the necessary scale – even if we don’t care about causing starvation by diverting land from growing food, there just isn’t enough land to grow enough biofuels to replace petroleum, and in any case all the mass-produceable liquid biofuels give a very poor energy return on investment. The second option is entirely viable technically, but it puts us at the mercy of the motor manufacturers, and it also depends on a rapid transition to a renewables-based electricity grid.

I do agree with your analysis of the ruling class reaction to the crisis. But they are few and we are many – and it is worth looking at how much more [though admitted still not enough] has been achieved in Europe, where the electorate understand the reality of the situation so much better than is the case in North America.