The problems with the textbook analysis of minimum wages

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the sorry state of the BC minimum wage, stuck at $8 after nine years two months and still counting. Yes, it will likely increase very soon, now that almost all leadership candidates on both sides have expressed support for higher minimum wages, but one has got to ask why it took so long.

A big part of the resistance to any increases seams to come from the commonly held — and untrue — belief that minimum wage hikes are a huge job killer. Why is this idea so pervasive in the media and in the minds of our legislators when it is not supported by the evidence? In fact, the empirical evidence hardly has anything to do with it since most people — including many trained economists — firmly believe that minimum wages increases kill jobs without having looked at any studies on the matter (if you want a quick summary of the state of the evidence, read this).

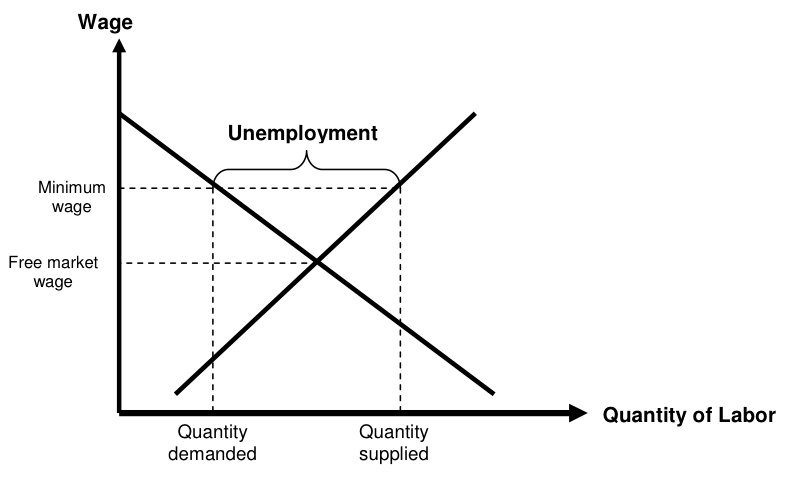

I am convinced that it’s those Intro to Economics classes that are to blame. Most media commentators and politicians have taken one, and they’ve all seen the following supply-and-demand diagram that shows the hypothetical effects of the minimum wage (or an increase of the minimum wage) in the labour market.

This simple diagram, which is staple of the introductory economics textbooks, is as misleading as it is powerful.

It makes you believe that that the minimum wage is set far above what a free-market wage would be in the labour market, which hardly ever happens. Because of that, the minimum wage is predicted to lead to a large increase in unemployment, which is defined as the number of people who have looked for work in the two weeks prior to being surveyed and who were not able to find work. By extension, any minimum wage increases would only move us into even higher unemployment territory. It makes sense intuitively and most people just accept that this is what actually happens in the real world without thinking twice.

But here’s what’s wrong with this graph in the words of Princeton University Professor of Economics Uwe Reinhardt, whose tongue-in-cheek essay The Art of Siffing Among Seasoned Adults: Can Economists be Trusted is an excellent read and must make for a highly satisfying first lecture:

In fact, however, the proposed minimum wage typically is just a shade above the prevailing free-market wage, or proposed increases are quite small relative to prevailing wage levels. In fact, they typically are so small as to have no perceptible effect on employment at all. Yet thousands of legislators, when confronted with minimum wage legislation, will automatically think back to their college economics courses and conjure up in their minds the dramatic illustration shown below.

A crucial detail about this graph that is often lost on unsuspecting economics learners is that the wage on that y-axis is expressed in real terms (i.e. adjusted for inflation) and not in straight up dollars. This means that if we’re looking at minimum wage policy over time, the only increases of the minimum wage that could be hypothesized to have any effects on unemployment are the increases after adjusting for inflation. In other words, regularly scheduled minimum wage increases to offset inflation would have no effect on the level of unemployment in equilibrium.

For the record, if BC had a policy of annually adjusting the minimum wage for inflation, we’d now be sitting at a minimum wage of $9.31.

Another big problem of the standard economics 101 approach to minimum wages is that the textbooks too often forget to tell students why governments would want to introduce regulations and constraints on the labour market in the first place. It is surprising how often the historical and political context is stripped out of the teaching of economics which makes both for poor education and for poor policy-making, once students try to apply these textbook graphs directly to the real world we live in.

It should be remembered that BC first introduced minimum wages (which at that time only applied to women) in 1918 because legislators wanted to protect vulnerable workers (in that case, women) from being exploited by employers. The reason why we have a complex system of employment standards and regulations is to promote fairer treatment of employees who don’t seem to do so well in the unconstrained markets (sweatshops, anyone?).

A decent minimum wage is a useful tool for addressing the huge disparities in the wage distribution that have emerged over the last 30 years in our province. Ensuring that minimum wage work pays enough to keep full-time, full-year workers out of poverty will make for a fairer BC and should be top priority for BC’s next Premier.

—

This post originally appeared on PolicyNote.ca.

Two things. First, the link to “Can economists be trusted” seems to be broken.

Second, it seems to me there are far more serious objections to that graph. There’s the basic fact that there can be no such thing as a free market, particularly in the labour market. There will be rules, and they cannot be completely neutral–if they don’t favour the workers, they will favour the employers. Even a rule as basic as “Workers aren’t allowed to get together in gangs, go to the owner’s place and rob him” or “Employers aren’t allowed to shoot employees who make the wrong demands” are constraints on the market, and quite real ones–both sorts of behaviour have been known to happen. Any graph purporting to show what the equilibrium would be in a completely free market is showing something that “isn’t right. It isn’t even wrong.”

Also, before labour unions came along economists generally agreed on something called “the iron law of wages”, which declares that “free market” wages will always tend towards bare subsistence. This seems to be pretty much true everywhere that the political power of workers is small–we’re headed in that direction now, although we still have a ways to go. Basically, workers need to eat, that’s why they work. And employers will be pleased to reduce workers’ wages well below what the employers need in order to make a profit. If there were perfect competition among employers that might not be possible, but there isn’t.

In terms of that graph, basically what’s highly misleading is that those two lines are assumed to be straight and at a 45 degree angle, creating that nice large and predictable distance between supply and demand of labour assuming a difference between the wage employers would offer and the legislated minimum wage. But in fact those lines are almost certainly fairly jagged, marked by verticalities and discontinuities. At the levels between markets setting subsistence wages and minimum wages, even generous ones, being set I suspect those lines are pretty much vertical, with supply exceeding demand by about the same amount right down to the sudden zig or at least sharp curve where the price offered is noticeably less than subsistence.

Finally, in our real political economy unemployment is something influenced strongly by lots of government policies, not just the minimum wage–and many of those have for decades been used more or less explicitly to actively increase the unemployment level, in order to “discipline” the workforce so that they don’t demand higher wages. This doctrine is advanced by precisely the same people who then turn around and say we can’t give the workforce higher minimum wages because it would increase unemployment. It’s self-serving nonsense, and while some of the people parroting it no doubt believe their own propaganda the point isn’t to reduce unemployment, the point is to make people poor so that employers can be richer.

Sorry about the broken link, should be fixed now. I came across the piece on the NY Times economics blog when I was preparing materials for an economic literacy workshop, and since then I’ve been using it all the time. Here’s the link to his NY times post: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/01/16/can-economists-be-trusted/

Interesting points, PLG, and ones certainly not covered in your run-of-the-mill economics textbook. That would be the stripping of historical and political context out of the teaching of economics that I refer to.

Fair enough.

Here is some recent empirical support from further down the left coast.

Iglika: Interesting explanation for why the empirical work doesn’t always match the theory on minimum wage changes. But if it’s the case that the minimum wage is only extremely slightly above the equilibrium, why bother with one at all? If the wage increase is hardly noticeable, what’s the point?

Also, do I take it from your argument that you agree that major changes to a minimum wage would likely lead to major job losses? Like a living wage, for example?

Even in the simplistic supply/demand graph, demand for labour should be measured as hours not jobs. So long as the increase in the hourly wage offsets any reduction in hours of work in terms of determining total income, minimum wage workers are better off from an increase in minimum wage. Richard Freeman pointed out a few years back that this is the case even in most studies showing negative impacts on hours.

Also, the simple model fails to take into account the productivity increasing impact of minimum wages. The impact on jobs from higher productivity in one sector should not be negative for overall employment since the higher wages will be spent and employers will invest

One thing the above chart assumes is a fairly elastic demand for labour through the relevant range. But, if the world of production and employment, especially in those industries were low paid work is located in numbers, is a more Leontieff or less perfectly flexible world, then the demand for lower skilled labour may be quite inelastic through some range. In that case, a minimum wage increase will have at most very small employment effects.

Minimum wages has lead a number of people un employed and so some one rather has their own business going or rely on working for less.

But on the other hand full time employees don’t really seem to feel it and so there is this complex system of employment stands and regulations just to promote fair treatment between the employee who doesn’t seem to do so well.