IWD 2014: The “girl effect” reduces inequality, but Canada can’t coast on that much longer

Every year when International Women’s Day rolls by, I can’t help but reflect on power, how it’s shared, and how women use the power they have. This year, I am struck by women’s power to reduce inequality, and not just to help ourselves. Women are key to reducing income inequality.

It’s been dubbed the girl effect, more powerful than the Internet, science, the government, and even money.

Canada is actually a poster girl (sorry) for the truth that education and hard work can transform not just lives but societies.

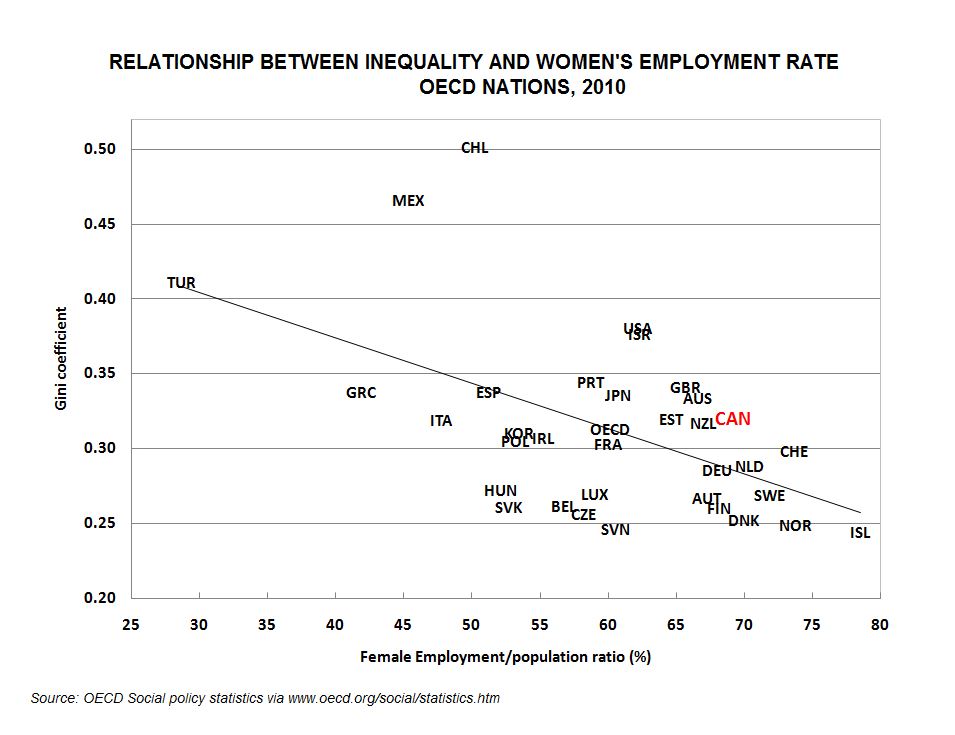

Look around the world and you’ll see a tight relationship between the level of income inequality in a nation and the proportion of women who work in the paid labour force, as the OECD chart unequivocally shows. (For more, see here.)

There is no simple link between inequality and growth, but we know the more talent you can unleash and develop, the more you can change the course of a community and its history. Often hard times are what unlock doors.

Every recession is a “he-cession”: men lose more jobs than women in a downturn because the first thing to slow is the production in goods-producing industries that are typically male-dominated (mining, forestry, construction, manufacturing). Every early stage of recovery is a “she-covery”: men who lose $30 an hour jobs wince at accepting $15 an hour offers, but women grab them to make sure the bills get paid.

This is a story about women’s determination and effort, but it’s also a story about public policy.

Canadian women propped up the economy during the Second World War and in response to each recession thereafter.

Women’s share of the Canadian job market has climbed steadily, in response to economic calamity:

o  17 percent in 1931

o  22 percent in 1951

o  34 percent in 1971

o  47 percent in 1991

o  50 percent in 2011

It’s just over 50% today. We’re trailing men in self-employment, but that, too, is changing.

Women now play a bigger role in the paid labour force in Canada than in the United States, and we tend to get paid better than our American counterparts, helping us offset inequality more here than there. Why?

Possibly because we have wanted, and have been able to afford, more education (65% of Canadian women over 25 have a post-secondary degree, compared with 40% of U.S. women). Or maybe the fact that we have more communities that offer subsidized child care. We need way more affordable child care and post-secondary opportunities, but we have more access to these critical supports in Canada than the U.S..

The trouble is, we’re pedalling faster to stay in the same place, and our strategies are running out of time. Median household incomes have barely held the line in the last 35 years  — which is, sadly, a better trajectory than in the U.S.  But “household incomes” now usually means two workers, not one; and this generation of workers is far more educated, as a cohort, than households in the 1970s.

The “work harder” nostrum has been taken seriously by Canadian women, who have warded off deeper inequality for the past 35 years. But it’s a time-limited option, not available for the next generation. Female employment rates increased by 40 per cent over the past 35 years. Among women of child-bearing years (25 to 44 years old) it went up a whopping 56 per cent.

It’s simply not mathematically possible to find the same boost in the coming years. Women are already working almost as much as men. (See Chart) There’s no “reserve army of labour” left in the kitchen.

We’re left with a basic equality: everyone only has 24 hours a day. How we use our allotment depends on how the market values our time and effort, and how public policy supports or plays against us.

Women have used their willpower and their staying power to improve the odds for themselves and their families. They’ve run out of time. So has the idea that Canada doesn’t have to worry about income inequality.

If the next generation is not to lose ground, businesses and governments are going to have to do more heavy lifting too. It’s not just women’s work.

International Women’s Day is a great day to think about these things. It shouldn’t be the only day.

Armine Yalnizyan is Senior Economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. You can follow her on Twitter @ArmineYalnizyan.

This piece was originally published at the Globe and Mail’s online Report on Business feature, Economy Lab.Â

“Every early stage of recovery is a “she-coveryâ€: men who lose $30 an hour jobs wince at accepting $15 an hour offers, but women grab them to make sure the bills get paid.”

If this is the case, does this drive wages downward and increase precarious employment? Wouldn’t it in some way this actually create more inequality?

Further to what Darlene wrote, this seems to be a case of oversimplification and selective interpretation.

Women’s increased labour market participation where a manpower shortage is restricting economic capacity would be a positive economic development. However, the second chart presented suggests no such shortage – men’s participation decreases as women’s increases. Factor in FT equivalence and it’s possible there was little if any net gain over the reference period.

The first chart on income inequality is misleading. First, it appears to contradict another chart posted here recently suggesting inequality was greater in Canada due to low union coverage (using a different inequality proxy). The second is that any impact of women’s increased participation would be relative to changing income inequality over the same period. As the author likely knows, Canadian income inequality has increased over most of the referenced period.

Lastly, the education statistics cited in the linked Economy Lab article are inconsistent with university enrollment statistics available from Statcan. Looking strictly at Canadian students, women’s share of total university enrollment is far less than 2/3 (closer to 56%), hasn’t increased dramatically (2% over the past two decades), and while gains in fields such as business admin and health sciences are noted, participation in so-called STEM fields actually decreased slightly over the same period.

I suspect the answer to this is “sometimes”. Note that she said “early stage”–what happens later in a recovery may be another question; in the past as recovery gained momentum and demand recovered, manfacturing jobs and other higher paid work would have recovered as well. This hasn’t been happening so much lately though; in the most recent “recovery” my understanding is that low-wage, precarious jobs are most of what’s been created ever since.