Declining pensions and bargaining power

[Cross-posted on my blog here.]

It’s relatively common knowledge that employer-run pensions have been scaled back over the past few decades. I’ve decided to dig up some data on pensions for this post to see just how this has taken place in Canada, motivated by a recently-released analysis of US pension reform that finds contradictions in how US workers have come to take on more and more of the risk for their retirement income.

First, a bit of background. There are two main kinds of employer-administered pension funds: defined benefit (DB) plans – where retirees receive a set monthly income, or defined benefit – and defined contribution (DC) plans – where retirees receive a variable monthly income dependent on how much they proportionately contributed to the pension plan and how this money was invested. There are also completely individualized retirement savings plans such as the RRSP, but these are essentially individuals investment accounts given preferential tax treatment. However, the link between RRSPs and DC plans is that they generally place investment risk on workers themselves; if whatever financial instrument the money is invested in suffers, retirement income also suffers.

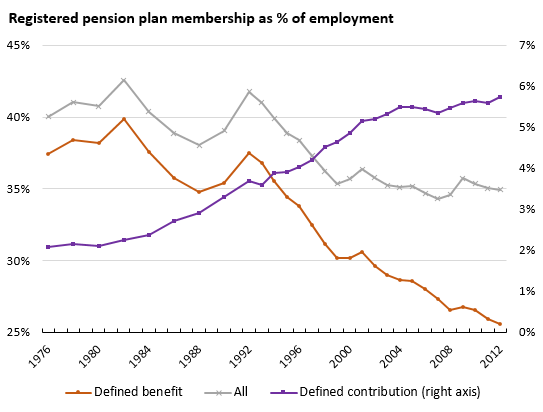

While some employers have eliminated pensions altogether, many have restructured their pension plans. Here’s the Canadian data on registered pension plan membership, plotted as a percentage of employment:

Figure 1. Registered pension plan coverage as a percentage of employment by type of plan (Source: Statistics Canada, CANSIM 280-0008 and 282-0008).

Employer-administered registered pension coverage has fallen steadily, but DC plan membership has nearly tripled (as a percentage so membership has grown by much more) since the 1980s. Indeed, in the absolute terms, the number of workers covered by a DB plan appears to have stabilized, while the number of those covered by a DC plan is rising fast:

Figure 2. Number of workers covered under types of registered pension plan (Source: Statistics Canada, CANSIM 280-0008).

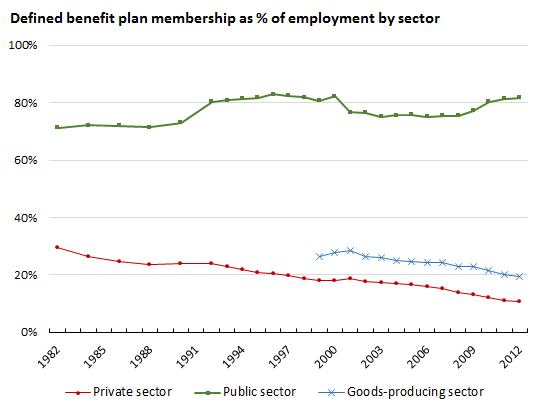

Finally, looking only at DB plans, it appears to be largely the demise of private sector DB pensions that is responsible for the drop in their overall coverage. In terms of the private-sector, separating out the goods-producing sector (almost entirely private, only limited data) shows that this sector has also seen proportional and substantial declines, with 5% smaller coverage in the course of just a decade.

Figure 3. Defined benefit plan coverage as a percentage of employment by type of sector (Source: Statistics Canada, CANSIM 280-0017, 183-0002 and 282-0008).

The context for this statistical adventure was my coming across the already-mentioned new article that delves deeply into the reasons behind the rise of 401(k) plans, a type of DC plan popular in the US, and fall of DB plans. It’s worth quoting at length. The author, Mike McCarthy, writes that pension reform in the US was “an instance of neoliberalism without neoliberals†where,

Regulatory agencies, seeking both to bolster the security of the DB system and to undermine unions with administrative control of their pension plans, unleashed torrent of legislation between 1974 and 1993. In the context of the increasing administrative costs of DB plans, a growth of small firms in the service sector and a decline in goods-producing industries, and the weakening of the labor movement, employers shifted into the DC system. While neoliberal policy makers mattered, they mattered in spite of their intentions, which were motivated in part to use stronger regulations to crack down on unions.

This meant that

New rules worked in such a counterintuitive way because of how the policies themselves functioned relative to changes in the balance of class forces between businesses and unions. Neoliberalism in the 1980s was not simply the weakening of state capacity or a state-managed project. By taking a “hard case,†one in which neoliberal policy makers were trying to maintain and expand the security of a policy area, this paper suggests that neoliberal rules worked in the way they did in large part because of the weakening of the labor movement and despite the conscious intentions of neoliberals themselves.

In short, policy changes theoretically favourable for workers that were aimed to protect DB plans also imposed high costs on business; the lack of bargaining power on the part of workers allowed business to get out of DB plans, in this way circumventing the new, stricter rules.

Canada has not gone through this same kind of process of regulatory change and may actually have some regulations that favour DB plans, among them higher management fees for DC plans, employee-paid contributions to DB plans and so on – all of which makes these plans relatively less expensive as opposed to what happened in the US. As such, the transition from DB plans to DC plans has been less pronounced but still there.

What has been the same in Canada is the relative decline in worker bargaining power visible in a (smaller then the US but present) decline of union density and the paucity of labour unrest. A range of factors including liberalized trade, real or imagined worries about profitability and the changing nature and extent of finance have been used to put pressure on workers to accept concessions.

Even with weaker labour, a good number of labour struggles have been fought over the relatively mundane-seeming topic of pensions. Just witness the current strike at Bombardier in Thunder Bay, where, among other things, workers are fighting to save not so much their own pensions as the right of future workers to the DB plan current employees receive. The company, on the other hand, is trying to impose a contract where new workers are subject to a DC plan. In the public sector, Montreal bus drivers protesting creatively to protect municipal pensions across Quebec. Such individual battles will contribute to big, decadal changes.

If McCarthy is right about the US and the story about Canada here is true, then the pension fight might not be won in parliament or in courts as much as on the picket line and in organizing drives. Strong regulation certainly helps, but the US story and Canada’s smaller decline show that building bargaining power may be the key to defending pensions and stopping the tide of risk being offloaded onto workers.

Would a defined benefit plan operate under the assumption that the firm they work for won’t go bankrupt and restructuring the pension sometime between the employee being hired and the employee dieing many decades later. That seems like a very risky assumption compared to the relatively diversified risk of a defined contribution plan?

Thanks for the comment! Defined benefit plans are protected from this kind of risk in several ways. First, the pension fund is separate from the finances of the employer so even if the employer goes bankrupt, the plan’s assets are safe and continue to be paid out (they’re held in trust for future retirees). It can happen that an employer underfunds a plan (so, say the plan holds assets that will only cover 80% of expected future pension payments) and goes bankrupt while the plan is underfunded. In this case, retirees may get somewhat less than 100% of their benefits but usually not much less for several reasons. There are rules that regulate how badly plans can be underfunded and for how long, there can be some limited form of pension insurance (like deposit insurance for banks; currently, Ontario has this) and, finally, when a company goes bankrupt it still holds assets even if it’s net position is in the negative and so the pension plan can be among the claimants during restructuring/bankruptcy proceedings. All of these regulations could be further strengthened to help secure pension earnings (stricter rules on underfunding, pension insurance in more jurisdictions, priority for pension trusts during bankruptcy) but, as I note in the piece, these alone will not solve the basic problem that pension coverage is declining.