Canada’s failed experiment with corporate income tax cuts

After a generation of comparatively high corporate income tax (CIT) rates, in the late 1980s Canadian governments at the federal and provincial levels began a series of corporate income tax reforms. According to many mainstream (“neoclassical”) economists, reducing CIT rates was a wise public policy. A reduced CIT rate means a reduction in the cost of capital, thus inducing a greater supply of capital. And because investment is a key driver of growth, reducing CIT rates leaves firms more (after-tax) earnings to plough into growth-expanding industrial projects. Did the halving of the Canadian CIT rate spur higher levels of investment and more rapid growth?

The short answer is no: far from improving economic outcomes, there is evidence to suggest that corporate income tax reductions depressed Canadian GDP growth. I present a detailed explanation of why that’s the case in a forthcoming study to be published by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Given the election debate around raising the CIT rate, I thought it worthwhile to summarize my findings. The study contrasts three Canadian corporate income tax rates: the effective federal CIT rate, the combined Canadian statutory CIT rate and the weighted average effective rate on the top 60 Canadian-based firms with five growth variables, namely investment in fixed assets, employment, GDP per capita, labour compensation and productivity. I conclude that there is no empirical or statistically significant relationship between CIT regime and growth. Business investment is a key determinant of GDP growth, employment and labour compensation, but over the long-term it is unresponsive to changes in the statutory or effective CIT rate.

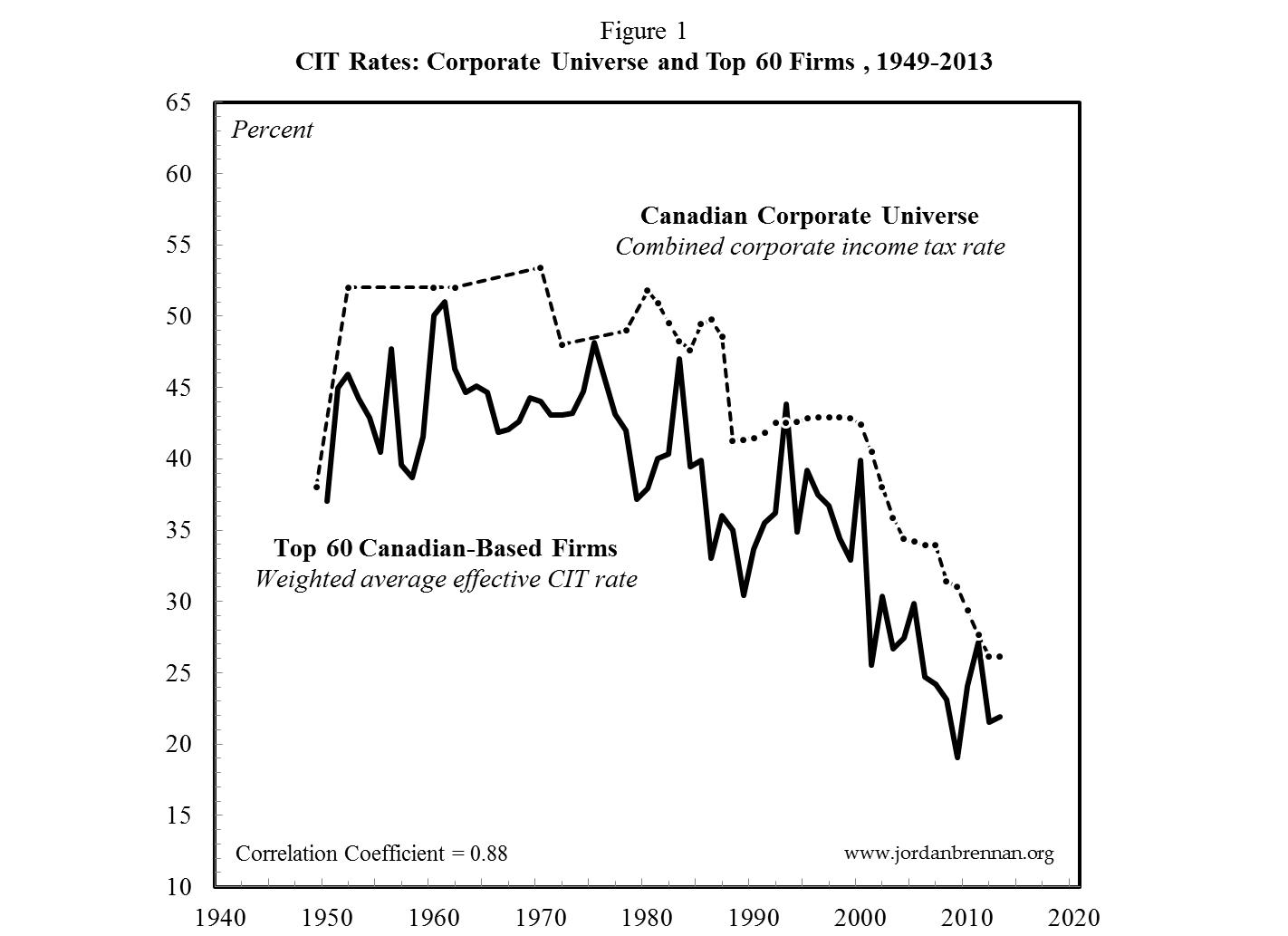

Consider Figure 1, which plots the combined statutory CIT rate for Canada and the weighted average effective CIT rate on the largest 60 Canadian-based firms (ranked annually by equity market capitalization). The first round of significant corporate income tax reform came in 1988, spearheaded by the Brian Mulroney Progressive Conservatives. Federal rates fell from 36 percent to 29 percent. The second round of corporate income tax reform came in 2001 with the Jean Chretien Liberals, which saw the federal statutory rate reduced from 28 percent to 22 percent in 2004 (where the rate already stood for manufacturing, resources and other ‘trade sensitive’ sectors).

The most recent round of corporate income tax reform was initiated by the Stephen Harper Conservatives in 2008, which saw a straight reduction to the statutory rate. In a five-step reduction program, statutory federal CIT rates fell from 21 percent in 2007 to 15 percent by 2012 (excluding the surtax of 1.1 percent, which was also scrapped by Harper). Over the past three decades the provinces have also taken a kick at CIT rate reduction can, cutting the statutory rate from an average of 14 percent in the late 1990s to 11 percent more recently. Both CIT rates in Figure 1 have been halved in the past three decades, with the bulk of the reduction coming since 2001. Did these reforms spur higher levels of investment and more rapid GDP growth?

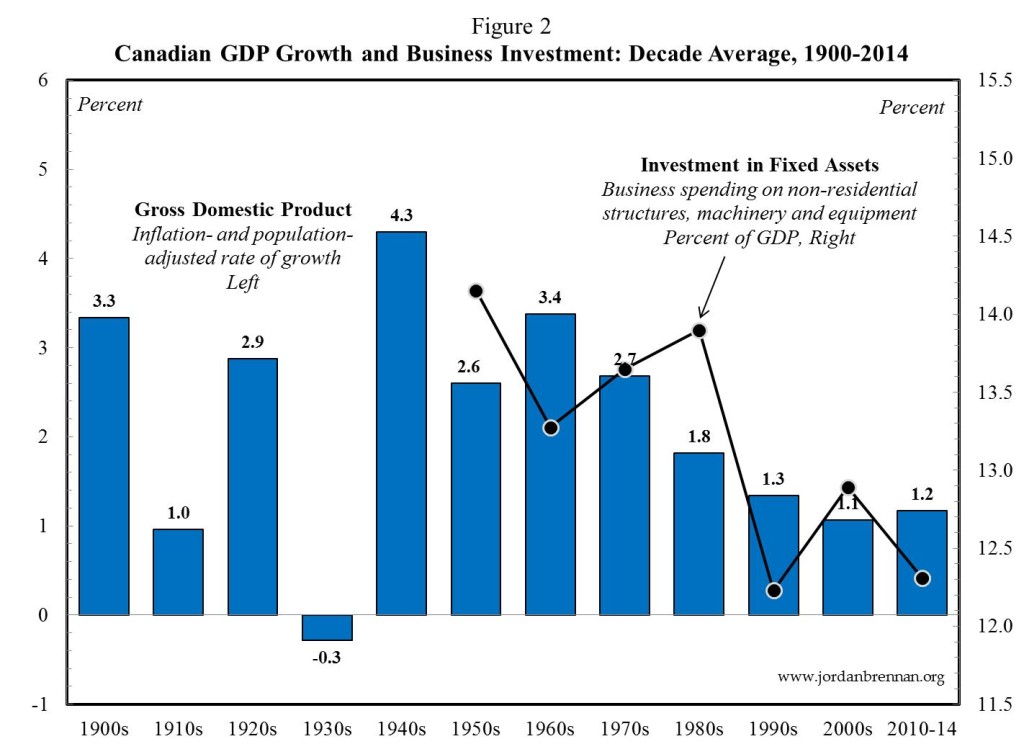

Figure 2 plots the deep history of Canadian GDP growth and business investment in fixed assets. The decade average rate of GDP growth is adjusted for inflation and population and the decade average level of fixed asset investment is measured as a percentage of GDP. Even though CIT rates began to be reduced in the 1980s, the 1990s and 2000s performed worse in terms of economic growth, not better.

The first few decades of the postwar era experienced an upward trend in investment. Significantly (and ironically), not only has investment failed to increase in recent decades in tandem with CIT rate reductions, the pattern that investment takes mirrors the CIT rate. Far from the CIT regime and growth being strongly and inversely related, there appears to be a positive association between the two variables, such that CIT rate reductions are historically associated with lower levels of investment.

Fixed asset investment averaged 13.7 percent of GDP in the postwar decades to 1980, but in the past three decades (whilst governments were fixated with corporate tax cuts) business investment fell to an average of 12.8 percent of GDP. In sum, when we contrast the experience prior to the CIT rate reduction era (1945-1988) with the CIT rate reduction-obsessed era (1988-2012), we see a move from heightened industrial capacity expansion and relatively robust GDP growth to capacity stagnation and the slowest GDP growth in post-Depression history.

Not only did Canadian CIT rate reductions fail to lead to faster growth, but my study also unearthed evidence which suggests that CIT rate reductions contributed to slower growth. By reducing CIT rates, Canadian governments contributed to the increased income position of large firms. Rather than investing their enlarged earnings into expansionary industrial projects, Canada’s corporate sector especially its largest firms have increasingly stockpiled cash on their balance sheet. This ‘dead money’, as former Bank of Canada Governor Mark Carney put it, is one ingredient in the heightened stagnation of recent times.

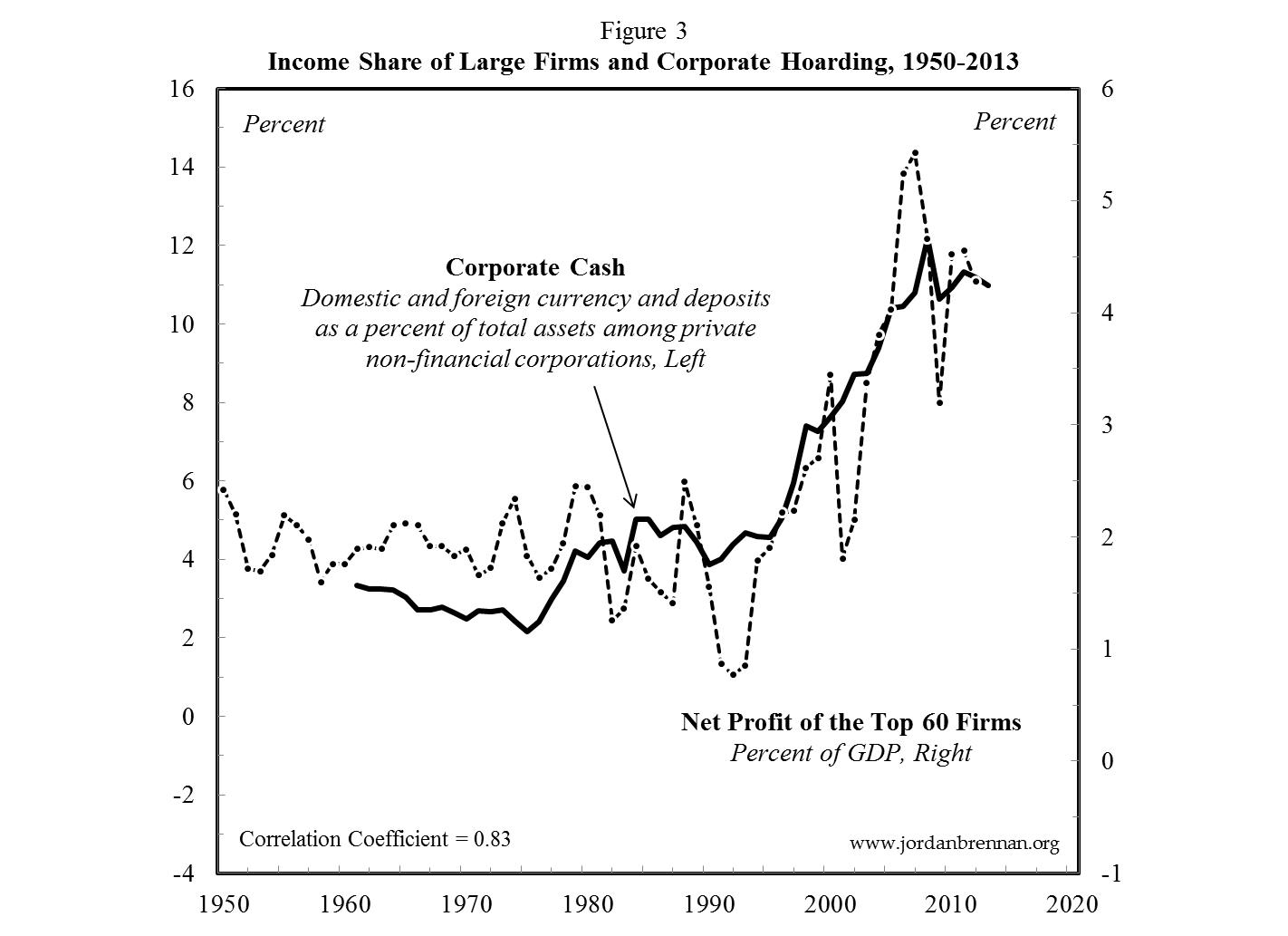

Figure 3 contrasts the income position of the top 60 Canadian-based firms, measured as net profit divided by GDP, with corporate cash the latter measured as domestic and foreign currency and deposits as a percent of the total assets amongst all private non-financial corporations. The two series are tightly intertwined over half a century. The fact that Canada’s largest corporations have doubled their income share in the past two decades in tandem with excessive cash hoarding indicates that the growth of corporate power itself might be one determinant of cash stockpiling, and hence, of slower growth.

As the leading firms claim a larger share of national income through enhanced size and market power, their capacity to stockpile cash increases. By hoarding cash these firms stabilize dividend payments, thus reducing risk, and this leaves them with more liquidity for acquisition activities and to hedge against market downturn. One consequence of the stockpiling of cash, then, is that a smaller share of national income is deployed to expand employment and industrial capacity.

There is another aspect to this story that bears investigation. The income share of the largest firms captured in Figure 3 is net of corporate income taxes. This means that the effects of changes in the CIT regime are built into the picture. If the hoarding of cash by large firms in an ingredient in slower growth, what is the relationship between the CIT regime and corporate hoarding? Figure 4 contrasts the level of corporate cash with the weighted average effective CIT rate on the top 60 firms. Note that the CIT rate is positioned on an inverted scale to facilitate its comparison with the level of cash.

There is a very tight, persistent and negative relationship between the level of corporate cash and the CIT rate. With every reduction in the CIT rate, rather than investing its enlarged earnings into expansionary industrial projects, corporate Canada stockpiled an ever greater proportion of cash on its balance sheet. This means that, counterintuitively, the government frenzy for CIT rate reductions has exacerbated corporate cash hoarding and depressed growth.

Despite being factually supported, this line of reasoning is entirely at odds with neoclassical doctrine. If the findings contained in the forthcoming CCPA paper are true, then corporate tax cuts will go down as one of the great Canadian public policy blunders of the past generation. Far from spawning higher levels of investment and growth, the government fixation with corporate tax cuts has indirectly fostered slower growth.

Jordan Brennan is an economist with Unifor and a research associate of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Follow him on Twitter @JordanPWBrennan. An attenuated version of this post can be found on the CCPA’s Behind the Numbers series.

Why do people keep saying that capital investment drives an economy and use that as a justification for lowering corporate taxes?

It’s consumption that drives an economy, pure and simple. High production levels are wasted if there’s no one to buy the result. Thus any well run company will only increase investment if it’s needed to increase production to meet consumer demand. No consumer demand, no increased investment.

In fact a quick study of history shows that increased consumption grows an economy. The rapid growth of the merchant class that predated the industrial revolution produced a stronger economy as the industrial revolution itself did. The great depression happened due to a slowing of consumption that didn’t improve till WW2 kicked consumption into high gear to supply the war effort. The massive growth of the middle class in the 50’s drove the economy to higher levels and the baby boom produced a tidal wave of consumption that produced a extremely vibrant economy.

The concept of “trickle down” economics is a flawed one that is only endorsed by the people that benefit the most from it. The people with high levels of capital. Capital is the blood of the economic body and it needs to be in constant motion moving through all parts of the body and benefiting all participants in the economic body.

Instead the level of capital turnover has been decreasing more and more, and we have a economy that only serves the rich. With a rapidly shrinking middle class, the true drivers of the economy, with ever increasing levels of bad debt as they try to continue to maintain a less and less viable western life style.

“far from improving economic outcomes, there is evidence to suggest that corporate income tax reductions depressed Canadian GDP growth”

The facts indicate that corporate tax decreases did not increase GDP growth, but what is the argument that it depressed growth?

Is there evidence that had taxes been greater, corporations would have invested more? That seems unlikely. Is there an assumption that governments would have invested more? Perhaps, but the federal government could always have spent more since it owns a central bank with a fiat currency.

In other words, the corporate tax rate in itself is probably irrelevant.

Perhaps we should look at government collusion in the neo-liberal assault on workers’ rights which led to a major shift in national income shares away from workers towards profits as productivity increased. In this view, low growth may be a consequence not of the low corporate tax rate but of weak demand caused by the failure of government to fill the output gap and to ensure full employment with a well-paid workforce.

__________________________________________________

Wage rises are required – real wages must grow in line with productivity

Bill Mitchell – billy blog, Modern Monetary Theory … macroeconomic reality

“Since the mid-1980s, the neo-liberal assault on workers’ rights (trade union attacks; deregulation; privatisation; persistently high unemployment) has seen this nexus between real wages and labour productivity growth broken. So while real wages have been stagnant or growing modestly, this growth has been dwarfed by labour productivity growth.

As a result, the wage shares in most nations have been falling. Where has the real income gone? To the profit share!

The declining wage share and the resulting credit binge in many nations were clearly causal in creating the global financial crisis. The mainstream economists believed that the markets were efficient and that there would be no problems with placing an increasing proportion of real income into the hands of the Casino economy.”

____________________________________________________

Abba Lerner: Functional Finance

“The central idea is that government fiscal policy, its spending and taxing, its borrowing and repayment of loans, its issue of new money and its withdrawal of money, shall all be undertaken with an eye only to the results of these actions on the economy and not to any established traditional doctrine about what is sound and what is unsound. This principle of judging only by effects has been applied in many other fields of human activity, where it is known as the method of science opposed to scholasticism. The principle of judging fiscal measures by the way they work or function in the economy we may call Functional Finance … Government should adjust its rates of expenditure and taxation such that total spending in the economy is neither more nor less than that which is sufficient to purchase the full employment level of output at current prices. If this means there is a deficit, greater borrowing, “printing money,†etc., then these things in themselves are neither good nor bad, they are simply the means to the desired ends of full employment and price stability …”

Greetings Gezzer and Larry Kazdan:

To your point, Gezzer, that the underlying purchasing power of the community shapes production/output, I think there is some truth to that. Recognition that investment drives growth does not contradict that claim. The two are not mutually exclusive. However, one needs income in order to spend, and for the overwhelming majority of people that means they need a job. And jobs are linked with investment. So rapid job creation without (i) sufficient purchasing power or (ii) actual spending will hold back growth, but growth will also be undermined without sufficient job creation.

And to Larry’s question about the reasoning behind CIT rates depressing growth, I tried to spell that out in my blog post. Canada’s corporate sector has increasingly stockpiled cash on its balance sheet. This means less funds are deployed in job-creating industrial projects. If cash hoarding has slowed growth, and if government’s have facilitated cash hoarding via CIT rat reductions, then governments have indirectly served to dampen growth. My forthcoming paper with the CCPA will spell these linkages out more formally–this is a blog post after all.

Thanks for your interest and your thoughtful comments,

Jordan

This is a very interesting piece, but I am unclear on several points. At the risk of getting out of my depth, let me enquire about just three:

1) What is meant by “hoarding”? Do not savings go somewhere? Joan Robinson was sceptical about about the idea, as she made clear in “The Concept of Hoarding†(Economic Journal, June 1938). In that piece, she notes that, for Keynes, the notions of “savings lying idle in the banks, and of banks’ loans as a supplement to current saving are purely mythical conceptions.â€

2) The author writes: “By hoarding cash these firms stabilize dividend payments, thus reducing risk, and this leaves them with more liquidity for acquisition activities and to hedge against market downturn. One consequence of the stockpiling of cash, then, is that a smaller share of national income is deployed to expand employment and industrial capacity.” I can see how having a large kitty of “stockpiled cash” might reduce the incentive to modernize plant and equipment. So this is a strong argument, but where do the funds disbursed in acquisition activities go?

3) It is written “Business investment is a key determinant of GDP growth, employment and labour compensation, but over the long-term it is unresponsive to changes in the statutory or effective CIT rate.” This seems a sensible analysis. But what then does drive business investment — the level and kind of public sector investment, external demand for Canadian goods, effective demand in the economy (in the sense of somebody actually being willing to buy something)? Public expenditures (at least at the federal level) are not dependent on tax revenue from corporations, though, are they? So, how can public sector investment, and public spending to boost aggregate demand, be constrained by low corporate income tax rates? And the argument seems to be that foreign investment and foreign demand for Canadian goods is not responsive to changes in corporate income tax rates. But is that not just to say that confidence for firms to invest depends on general global economic conditions, on the one hand, and, on the other, the extent to which aggregate demand is supported by public spending and tax expenditures?