How do you solve a problem like precarious work?

Finance Minister Bill Morneau has taken quite a bit of heat for his tone deaf comments about the reality of precarious work, specifically saying that we should just “get used to job churn”. His policy prescription, an improved social safety net, is actually a valid part of the solution. But must we accept that the precarious will always be with us? That is, what can government actually do to address precarious work?

First of all, has the Finance Minister accurately understood the issue? There is a great deal of hubbub about precarious work, can it be reduced to simply “job churn”?

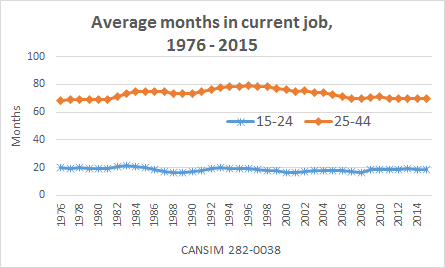

Hmm, apparently not. The average duration of a job has been remarkably stable since 1976, even for young workers. The distribution is pretty stable too, and aside from the obvious impact of recessions, there is no clear upward trend in short term jobs.

This is because for many workers, precarity doesn’t mean jumping from job to job – it means not knowing how many hours you can count on next week, it means not having any benefits, it means balancing multiple jobs along with caretaking duties and/or furthering your own education. It means working for the same employer for 5 years, but always on six month contracts. It means unpaid internships are the only kind of internship you can find, or not having any recourse when an employer unjustifiably docks your wages or takes your tips for themselves.

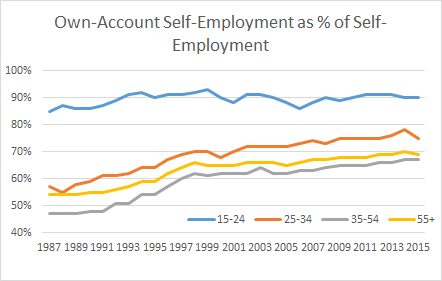

Of course there has been an increase in own-account self-employment (has no paid help, but may be incorporated or unincorporated), and contract workers wouldn’t show up in the data on job duration. But the trend in own-account self-employment is most pronounced for workers 25-54.

Our labour statistics don’t do a good job of measuring precarity – but some indications:

- Nearly 2 million workers are ‘own-account self-employed’, meaning they have no paid help,

- About 900K work part time because they can’t find full time work,

- Another 390K work part time to accommodate unpaid care work,

- About 1 million have a second or third job.

So, now that we have a better understanding of the problem, what tool(s) does the federal government have at its disposal to address labour market precarity for younger and older workers, now and into the future?

The federal government can try to spur economic growth. The current government is doing that through investment in infrastructure (watch out for privatization schemes here), and investment in green jobs and clean tech.

But the economy has been growing over the past 25 years, when we’ve seen growing precarity in the labour market – so that’s clearly not sufficient. I would advise the economic council to take a look at Senator Bellemare’s work on full employment, and Professor Marc Lavoie’s work on wage led growth. It might lead them in a policy direction that will benefit both growth and well-being.

For example, transfers such as the Canada Child Benefit will help to reduce poverty and inequality. Expanding the Working Income Tax Benefit would help make work pay, and make life a little easier for the working poor.

Expanding the social safety net by improving CPP will help down the road, and it absolutely reduces the stress of precarity when workers know they will have that pension when they retire.

The current design of Employment Insurance amplifies and exacerbates labour market inequalities, and ideally a social insurance system would work to dampen existing inequalities. A lower entrance requirement & minimum benefit level would go a long way to doing that.

The federal government could use Labour Market Development Agreements (LMDAs) with the provinces to provide more opportunities for training and re-training – and better supports for non-EI eligible workers who need access to basic numeracy and literacy training through Labour Market Agreements (LMAs).

High quality public services and social services are critical. I cannot overstate the need for more affordable childcare spaces in Canada, and the beneficial impact this would have on precarious workers.

But it’s not all about the federal government, since the provinces legislate employment standards for about 90% of workers in Canada.We’re hearing lots about $15 and Fairness, because that’s where the issue is for many precarious workers. Higher minimum wages, access to paid sick leave, the ability to certify a union in one step instead of two-stages (leaving workers open to retaliation and intimidation from employers), anti-scab legislation, and most importantly, proactive employment standards enforcement, like Manitoba has.

(Instead of relying on complaints from affected workers, Manitoba has a Special Investigations Unit that monitors the employers of vulnerable workers. According to their website, in 2014-2015 almost half of their investigations were the result of information received from the public and the Unit identified violations in 80 per cent of these cases.)

So what can government do to address precarious employment? A whole lot, it turns out.

Is Slow “Growth” Inevitable?, Jim Stanford, PEF, July 21st, 2016

“New talk of “helicopter money” strategies (whereby a central bank would create new credit and directly inject it into the real economy, to support investment, government programs, or consumption) confirms that if we collectively decide we need it, and enforce our will on our political and monetary leaders, we could create all the money needed to finance real, productive work. So long as millions are languishing without a job, there does not appear to be a good argument against doing so. To the contrary, if it helps us put an end to pollution (including greenhouse gases) and poverty, an all-out war-like mobilization seems like a no-brainer. Living standards would grow, taxes would be paid, the environment would be protected, and real GDP would grow rapidly, though that’s not the point.

Of course, there are many problems and challenges associated with an all-out economic mobilization of the sort associated with World War II. But the basic point that every economic resource, and every willing worker, can be put to work when society decided it is important enough to do so, is valid in every economic context.”

The Social Enterprise Sector Model for a Job Guarantee

http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2014/01/social-enterprise-sector-model-job-guarantee-u-s.html

“Imagine 25 million people with no income or precarious forms of income. Now imagine 25 million with a decent base wage. The effect on the private for-profit sector would surely be more stable demand, ringing cash registers, increasing profits, growth and, yes, a lot more better-paying private sector jobs.

***

The experience of the New Deal and Argentina’s Plan Jefes shows that such programs can be up and running in 4 to 6 months and useful tasks can be performed even by the least skilled and least educated citizens.”

This ignores the “Tsunami” of work displacement caused by automation. Everybody is saying what a wonderful thing but those of us who remember the promised “leisure society” ((which never came) this nirvana will be pure hell unless the government implements a guaranteed annual income financed by the gains to corporation’s bottom line produced by automation.

Any bets on rich bill morneau even acknowledging the problem>

The remedies you have suggested are all beneficial and would go a long way towards moving the working poor out of poverty. The real problem, though, is employers. Low wage employers more often than not cut their wage bill even farther by hiring large numbers of part time workers in order to save on benefit costs like pensions, paid sick leave, and health insurance. Increasing the minimum wage or CPP is good but it still wouldn’t be enough to let a person go from 2 or 3 jobs to one. It strikes me that the added costs in childcare, transportation, and so on would make it more difficult for part time workers to enjoy a sustainable standard of living.

May I suggest one more remedy. Part time or precarious workers are more likely to use more social services than full time workers with benefit packages. In other words, these companies are depending on social services in order to keep wage costs low and increase profits. Isn’t it only right that companies that use a large proportion of part time or contract workers be asked to pay more into things like EI, and CPP, and healthcare costs? This is not discrimination. This is leveling the playing field with companies that treat their employees well.

A lot of the issues are happening at the margin in Canada’s various labour markets. The presence of quite large numbers of TFW’s have a disproportionate effect on precarious work. Same thing with the gradual shifts away from training, and supporting job transitions through Manpower and the like. Small changes that have huge impact, especially over the two decades they have been worming their way into our lives. Biggest problem I can see is that employees are bearing the brunt of training costs. Unpaid internships should be illegal. Seriously, they are grotesque.

I agree, the overall issue behind precarious work is a shifting of risk from employers to workers, and a shifting of responsibility away from gov’t to the individual.

I agree with George Norman that one thing that needs doing is a comprehensive reform of the taxation and taxation-like and regulatory environment that makes it cheaper for employers to use precarious workers. Doing so, we should bear in mind that part of the reason that environment exists is precisely due to lobbying from businesses who wanted to use more precarious workers.

It’s also I think important to get back to the Keynesian idea of the government as an employer of last resort. It’s not like we don’t have anything useful needs doing that the private sector ain’t getting done.

But in the longer term, the automation issue also points to a considerably shorter work week. If there’s less work then spread it thinner so everyone can have some. Production and productivity are high enough, there’s no fundamental reason a shorter work week shouldn’t command a living wage.