A Warning from Australia on Scheer’s Climate Non-Plan

Andrew Scheer argues carbon pricing is the wrong way to limit GHG emissions. He has pledged to eliminate the federal carbon pricing system, promising that scrapping it will bring down the cost of living and unleash more business investment.

Most economists disagree. And all of the other major parties include carbon pricing of some form in their respective plans to meet Canada’s Paris commitments. So Scheer’s approach is a clear outlier, both intellectually and politically.

Scheer claims his plan to eliminate carbon pricing, eliminate energy efficiency standards, and provide subsidies to “green” corporate investments would still allow Canada to meet its Paris targets. Most climate policy experts scoff at this claim. On Friday September 27 – the same day almost a million Canadians marched as part of the global Climate Strike initiative – he announced a new pledge to build bigger roads, laughably suggesting that too would reduce emissions.

There’s a real-world natural experiment to help judge the impact that Scheer’s plan to eliminate carbon pricing, and replace it with broad subsidies to business, would have on Canadian greenhouse emissions. Interestingly, Canada’s election debate on this issue is almost a perfect reprise of the 2013 federal election in Australia. The then-government there, under the Labor Party (led alternately by Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard), had just implemented a national carbon pricing system. Beginning in 2012, about two-thirds of Australian emissions began to be taxed at $23 (Aus.) per tonne of CO2 equivalent. Gasoline (called petrol down under) did not directly incur the carbon tax, but fuel taxes were raised by an equivalent amount.

Revenue from the new taxes was recycled back into the economy, primarily through income tax cuts targeted at low- and middle-income households. In particular, the government dramatically raised the low-income tax threshold, substantially increasing the number of low-income Australians who pay no income tax at all. Therefore, as in Canada today, the net distributional impact of carbon pricing plus offsetting tax measures was mildly progressive.

The right-wing Coalition party (led then by Tony Abbott) railed against the carbon tax, damning its supposed effects on energy prices, household finances, and business investment. It was an important issue in the election, and Abbott (whose position was strongly backed by the right-wing commercial media and powerful mining interests) won the election.

The tax was then eliminated effective July 2014, replaced by a scheme offering incentives to companies for improving energy efficiency (called the Emission Reduction Fund). This is almost a deja vu scenario to the choice facing Canadians today.

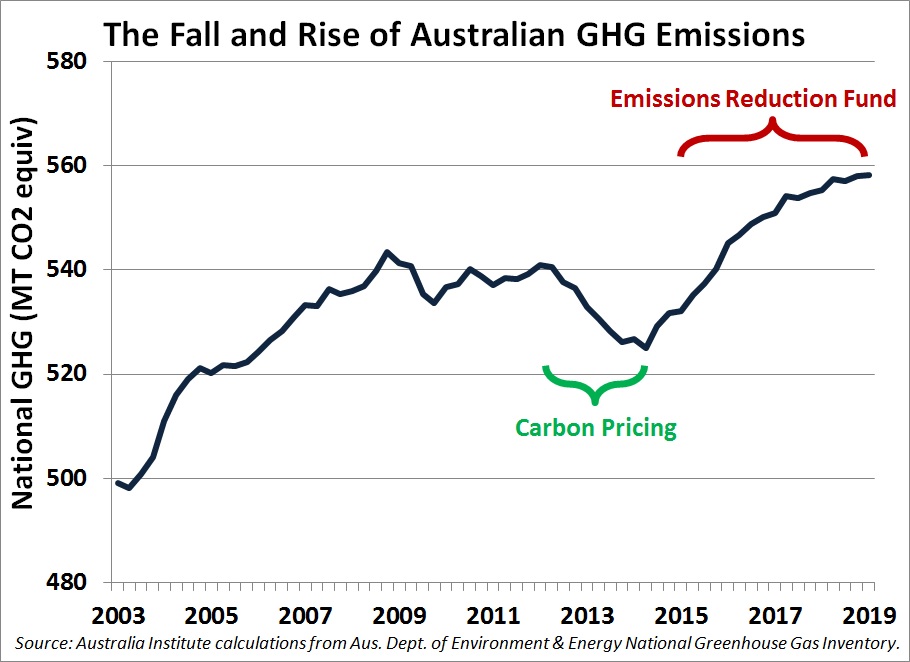

The results of the Australian natural experiment are stark:

Rarely are the impacts of an economic policy so clear and irrefutable. Emissions fell by about 4% in just the 2 initial years of the carbon pricing scheme. But since eliminating the price in mid-2014, emissions have grown by 7% – and they continue to grow. The government claims Australia is still committed to its Paris targets, but Australian emissions are steadily rising, not falling: it’s now one of just a handful of OECD countries whose emissions are higher than they were even a decade ago.

As far as the impact on consumer prices and business investment, Australia’s economy has performed worse on both counts than Canada’s since 2014. For example, the OECD’s aggregate measure of energy price inflation grew 8% in Australia between mid-2014 (when carbon pricing was axed) and end-2018. In Canada, average energy prices fell 7% over the same time.

Business capital spending in Australia has been abysmal since carbon pricing was removed: real business investment fell by a cumulative 17% over the five years after carbon pricing was eliminated. That’s not because of the change in carbon pricing, of course; but Abbott’s claim that stopping this “tax grab” would somehow unleash the forces of private accumulation was always nonsense. The decline in Australian business investment over this time was twice as steep as the parallel decline in Canada. Investment in both countries has been historically dependent on resource projects, and that’s a problem for both Canada and Australia: but that’s a structural issue that is neither solved nor exacerbated by carbon pricing.

n sum, neither consumers nor businesses in Australia realized benefits from the elimination of carbon pricing there. Australia’s international reputation on GHG policy has been (rightly) trashed: PM Scott Morrison’s recent combative speech to the UN climate meeting was widely ridiculed. And Australia was the sole member country at the recent Pacific Islands Forum blocking consensus on a statement regarding actions to reduce emissions – seriously damaging relations between Australia and its neighbours (many of whom will literally be submerged by rising sea levels).

Perhaps worst of all, the political legacy of that 2013 election defeat has been a destructive polarization in public discourse around climate policy. It’s so virulent that the opposition Labor Party, which just lost another election in which climate policy loomed large, has been left confused and paralyzed: cowed by the power of the mining industry and the private media, and now furiously backpedaling on several climate issues because they have been convinced (wrongly in my view) that it cost them at least 2 elections.

This very negative experience confirms that the stakes on climate policy are incredibly high in this Canadian election. Scheer’s claim that he can abolish carbon pricing and efficiency regulations, yet somehow keep us on track for Paris, is as laughable as Abbott’s similar claim in 2013. Canada would surely experience the same outcome as Australia: a reversal of current (modest gains) and a resumption of increasing GHGs. And if Canada’s existing (imperfect) climate policy framework is defeated and replaced with Scheer’s non-plan, the political damage will be felt globally. In the wake of Trump’s wrecking crew, Morrison’s re-election in Australia, and other backsliding around the world, a Scheer victory would constitute an enormous defeat for the climate.

So by all means, let’s have continuing debate about how to strengthen Canada’s approach. But preventing Scheer from emulating Australia’s U-turn on climate policy should clearly be an overarching priority.

It’s been a long time now that I decided Stanford was the only economist who ever made any sense to me, an engineer. The rest of what I’ve studied, read or had harangued at me has been fluff theory and academic nonsense, leading to the old adage: “If you laid all the world’s economists end-to-end, they wouldn’t reach a conclusion.”

For a rule to be valid, they say there must be an exception. Stanford is it for me.

So, apparently fed up with the lack of response to his obvious common sense here in Canada, off he went to be employed in Oz. Where there seems to be at least as much lack of critical thinking in politics as there is here. Giant coal mines for India is about as bright as Kenney wanting to flood world markets with tarsands diluted bitumen, euphemistically called “heavy” oil.

The exception in Oz to traditional conservatism is the high minimum wage, which seems to work all around, but try telling the bozo Conservatives here in Canada that. They prefer to crap on less well-off Canadians from a great height, rolling back minimum wages while primping their own lizard-level ego feathers, and going on about unions being awful. And the trouble is, probably about 40% of Canadians believe this nonsense, based on opinion from repetition and nothing else. It is merely a divide and conquer tactic that flatters citizens into thinking they’re rugged individualists, making them easy targets for “austerity” programs, and accepting of no wage increases for “the good of us all”.

Because most living citizens have only lived in a society where the gains unions had wrought from the wealthy occurred so long ago they have no memory of what things used to be like, they imagine things have always been like this. The same stupid attitude is shown by anti-vaxxers. They should have been alive in the 1950s as I was when polio, TB and measles were a constant worry. They similarly believe things have always been like they are now. I lost three childhood friends to diseases when I was growing up, and I was born in 1947. You can bet I keep my shots up-to-date.

.

Thank you very much Bill for that very thoughtful comment!

Hi,

On twitter, I gave a boost to Jim’s work presented here. I received some pushback about sources. So, I found the original data here:

https://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/128ae060-ac07-4874-857e-dced2ca22347/files/aust-emissions-projects-chart-data-2018.xlsx

I was able to 100% match Jim’s graph using the data for Figure 3, when I exluded the LULU category. I will leave it to field experts to tell us whether excluding LULU is best. But a good lesson here is that Jimbo’s work is trustworthy!

The entire dataset that you referenced was ‘projections’ … you might as well have just left your opinion and called it a day.

That is not true Robert, it is actual data up to end of the March quarter 2019. Like most aggregate statistics they are “estimates” (based on survey data), but it is not a projection.

The Australian data is from its:

“Quarterly Update of Australia’s National Greenhouse Gas Inventory for March 2019”

Google it and it will take you to the quarterly report.