Confusing “Deficit Elimination” with “Prosperity”

The banner headline across the top of the front page of the national Globe and Mail edition caught my eye Saturday morning: “How B.C. became a ‘have’ province.” Wow, I thought to myself, that is quite something (and without a single LNG plant yet visible on the horizon!). So I prepared to sit down with my coffee to give this startling news a good read. After all, any economist who follows interprovincial fiscal affairs in Canada knows well the fundamental economic schism in Canada: it’s between the 3 provinces with oil (Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland & Labrador) and the rest of the country. Measured by GDP per capita relative to the Canadian average, the 3 oil-producing provinces have constituted the “have” portion of Canada since 2006, while every province without oil is on the “have-not” side of the ledger. Newfoundland displaced Ontario from the “haves” in 2006. Saskatchewan joined the “have” club two years earlier. Traditionally B.C. had been a “have” province, but lost that status in 1995. In barely a decade the oil boom (while it lasted, anyway), and its side-effects on the other export industries crucial to the economies of other provinces, dramatically reshaped Canada’s economic, fiscal, and political balance. For B.C. to suddenly rejoin the ranks of the “have” provinces was shocking. How was this triumphant result achieved?

Imagine my confusion, then, when I perused page A18, and the full story by Justine Hunter, to find not a single word about B.C. being a “have” province. Not a single reference to its GDP per capita in relation to Canada’s. Not a single mention of the province’s equalization subsidy ending (which is what happens when you become a “have” province), to be replaced by a net outflow to the rest of Canada. The whole story was simply an incredibly uncritical review of how B.C. achieved three consecutive budgets without a deficit.

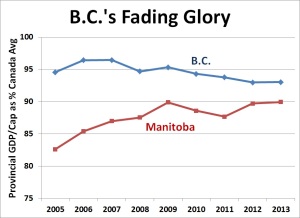

In fact B.C. is not a “have” province at all, and its relative position in Canada is getting worse, not better. It ranks 5th in GDP per capita among Canadian provinces — the same position it’s held since 2005. (In 1982 B.C. ranked second.) In the last six years B.C.’s relative GDP per capita has fallen from 97% of the Canadian average to 93%. Of particular interest is the fact that B.C. may soon be passed by Manitoba, and hence become the poorest province in the West (by this measure anyway — B.C. has many other benefits, of course!). Manitoba has increased its relative standing steadily, and is now just a couple of percentage points behind B.C. And by the way, Manitoba has not obsessed about eliminating deficits. Instead it has worried more about investments in physical and human infrastructure — and its economy is improving accordingly. (Business-friendly journalists, of course, regularly deride Manitoba’s NDP government for its fiscal policies, at the same time as they praise B.C. — consistently ignoring Manitoba’s rising relative position.)

Newspaper headlines are not written by reporters, so we cannot blame Ms. Hunter for the highly incorrect p.1 banner headline. But the headline writer could be forgiven the error (assuming they weren’t trained in economics and hence aware of what is implied by the term “have” province), given the enthusiastic, almost breathlessly positive tone of the full article. It provided a very positive review of Finance Minister Mike de Jong’s emphasis on tightly controlling expenditures, giving honourable mention to B.C.’s diversified economy and the accelerating recovery in the U.S.

I found especially objectionable the article’s uncritical cheerleading for expenditure restraint, praising the government for below-average per capita spending on health care and education, and for welfare rates that are “frozen in time.” Why are these things assumed to be “good”? To the contrary, the lasting debts that B.C. is accumulating by underinvesting so badly in its people, its infrastructure, and its environment belie the government’s phony claims about living within its means and protecting future generations. The article included just one critical quote (from the NDP finance critic) versus seven bullish quotes from Mr. de Jong (along with a gratuitous depiction of his “famously thrifty” personal habits).

B.C.’s relative economic performance has in fact been slowly fading throughout the Liberal government’s tenure. It turns out that just balancing a budget does not imply automatic prosperity after all (and if deficit elimination is achieved through austerity, it hurts prosperity, not helps it).

Maximizing GDP per capita is not the goal of economic policy, and perhaps I shouldn’t worry so much about one article that so objectionably internalizes the ideology of austerity (accentuated by a wildly inaccurate headline). But I do think this article constitutes an extreme and cautionary example of how the assumptions of deficit elimination have been so deeply swallowed in our national economic discourse, that people actually think “deficit reduction” and “prosperity” are synonymous. Remember: a government can eliminate its deficit, or even shut down entirely, but that hardly implies that society is richer.

The article concludes by uncritically quoting Mr. de Jong’s hackneyed kitchen-table wisdom: “We’re better off as a country when governments aren’t spending more than we take in.” Gosh, there’s a phrase I’ve only heard about a million times before. Never mind that all other economic constituencies (including businesses and households) regularly spend more than they take in. Never mind that economists of all stripes agree that governments must spend more than they take in when the economy demands it. More fundamentally, this obsessions with deficit elimination simply misses the whole point about economic progress. Once the deficit is gone, then what?

Keynes would not support fiscal austerity

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=18523

Australian Economist Bill Mitchell:

The fact is that the budget outcome should never be the

goal of policy. The goal should be to maximise real

outcomes and maintain price stability. The problem is that

in elevating the budget outcome to the centre stage and

setting artificial rules, governments are very likely to

damage prosperity.

They will typically also undermine the achievement of

their own targets into the bargain because the fiscal

austerity will reduce growth …..

It is a far better strategy to forget about the budget

balance and concentrate on environmentally-sustainable

growth and prosperity via well-paid employment.

A) “THE goal of economic policy, ”

It’s puzzling, not to say disturbing, to see a technologist use the definite article here, as one might refer to “the” speed of light. Surely ‘goal’ is a political concept, &the job of the economist, like any other engineer, is to advise how(if at all) any particular goal may be achieved, with estimates of schedule, $cost, and possible collateral damage.

B) Re ‘BalancedBudget’

As you so eloquently point out, a balanced budget is no Tetracyts. However, as one born before Winnie was dumped in favour of Nye & Clem, I was raised to ‘SaveForRainyDay’ & despise the folly of the ‘Never-Never’.

Seriously, tho’; what does PositiveEconomics say about postponing expenditures until the money is in the bank? How is it different for the individual & the collective? Is Norway really smarter than Alberta?

Re: How is it different for the individual & the collective?

Fiscal austerity – the newest fallacy of composition

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=10547

“In first semester of a credible macroeconomics course, students learn about the paradox of thrift – where individual virtue can be public vice. So when consumers en masse try to save more and nothing else replaces the spending loss, everyone suffers because national income falls (as production levels react to the lower spending) and unemployment rises.

The paradox of thrift tells us that what applies at a micro level (ability to increase saving if one is disciplined enough) does not apply at the macro level (if everyone saves aggregate demand and, hence, output and income falls without government intervention).”

Oh, is Norway smarter than Alberta? Well, Alberta has been giving oil away to corporate interests, which eventually burn it, contributing to climate change. At the same time, it becomes more and more dependent on giving oil away, while the people of Alberta pay low, regressive taxes and receive substandard services. Norway, on the other hand, turns its oil revenue into euros and ploughs them into the international stock market, where they feed stock bubbles. It takes big risks extracting that oil too, from under the sea, only to sell it to corporate interests, which burn it, contributing to climate change. The money does nothing for Norwegians because using it would trigger inflation, but if the oil ran out, they could spend in their own currency up to the point where it started to trigger inflation. (Put italics on the last bit of that sentence if in your mind, please.) So neither approach seems that smart, really. Norway’s approach would at least make a lick of sense for Alberta, since Alberta can’t issue its own currency, though even then Alberta would be much better off collecting more royalties and spending them on something useful, like promoting alternative energy and energy efficiency in the province our outside it, or enhancing productivity in other areas so it can leave the oil where it is. Which is what Norway should be doing too.