Yes, Virginia, Supermarket Profits are Still a Thing

Canada’s federal election has focused quite appropriately on the existential economic and sovereignty threat posed by Donald Trump. But there are other issues on voters’ minds, too, and continued concerns with ‘affordability’ rank high on that list.

Incidentally, on that point the Centre for Future Work’s recent report, Counting the Costs: Impacts of the 2022 Oil Price Shock for Canadian Consumers and Workers, provides some badly-needed perspective on why affordability became such an issue after the pandemic. No, it wasn’t government spending too much on CERB benefits, or the Bank of Canada acting as Justin Trudeau’s ATM, or immigrants driving up housing costs. And no, it wasn’t even the carbon tax. The oil price spike of 2022, transmitted directly to Canadian consumers and supply chains, was by far the largest single cause of the acceleration of inflation that has bedeviled Canadians since (including via the Bank of Canada’s interest rate hikes). Most maddening is that there was no real supply-and-demand explanation for that oil prices spike; oil supply (globally and in Canada) continued growing throughout 2022, even through the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Financial speculation on futures markets, not a genuine supply shock, is the culprit.

Inflation has come back down to target, but price levels still seem high (that’s how it works: when inflation stops, the price level stops rising, but is still higher than it was before the inflation). Canadians’ anger at that should be directed at the true causes of the problem, not at phony ight-wing scapegoats (like taxes, deficits, climate policy, or work-from-home arrangements in the public sector).

Speaking of scapegoats, a lot of vitriol has been directed at supermarkets for the rise in food prices since the pandemic–and rightly so. There are many causes of higher food prices, of course–including the trickle-down impact of fossil fuel costs through the food supply chain (see Zoe Yunker’s excellent story in The Tyee on the “Counting the Costs” report for some discussion of that angle). But there is absolutely no doubt that food retailers, dominated by the major chains (the top 5 control 80% of food sales in Canada), took advantage of rising inflation, shortages, and consumer confusion to increase profits on the backs of Canadian shoppers.

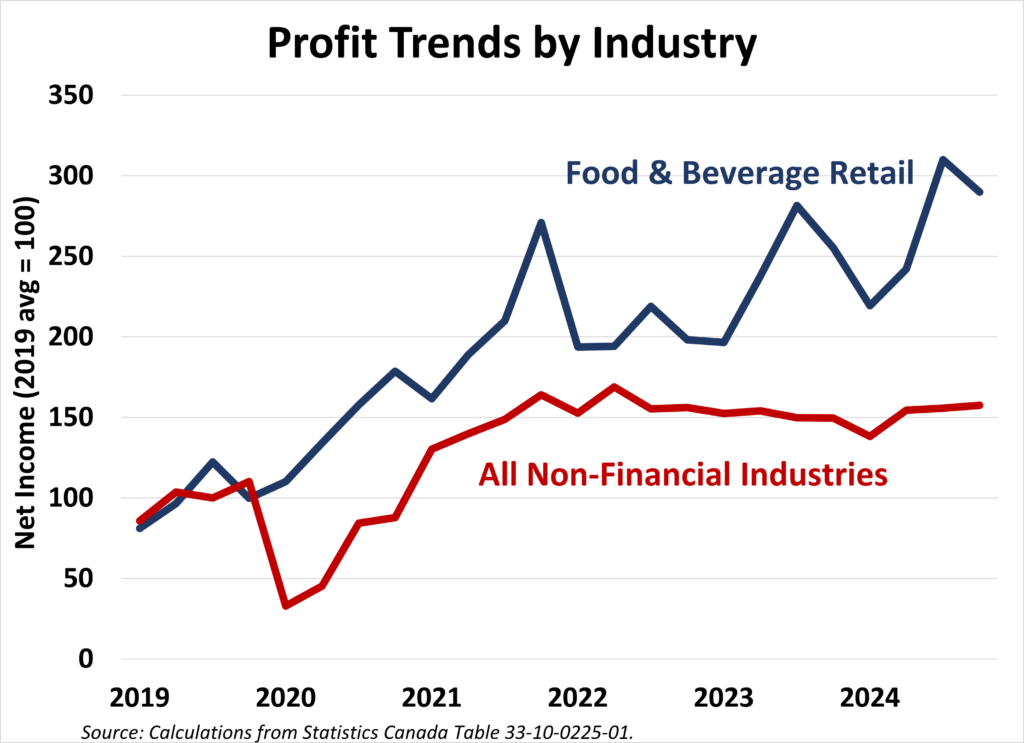

Grocery chain CEOs and free-market economists scoff at the idea that supermarkets (or any corporations, for that matter) “caused” inflation with their higher prices and profits. Inflation can only be caused by too much money supply, or excess demand–not by corporations wielding their power to pro-actively set prices. Greed has always existed, of course. But the unique (and thankfully temporary) disruptions of the pandemic allowed greed to go to town. Particularly in industries occupying a strategic place in the macroeconomic supply chain, and/or selling essential goods which are purchased no matter their price, profits shot up unduly and unjustly. There is plenty of evidence globally and in Canada about the existence and consequences of profit-led inflation. In Canada profits surged to their highest share of GDP in history in 2022, alongside inflation. And as profits (in most industries, not all–see below) moderated, inflation returned to normal.

In his campaign, NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh is addressing the problem of food prices with a multi-part agenda to reduce food prices in Canada, including a compulsory Code of Conduct for grocers, stronger powers for the competition bureau, and a price cap on a modest basket of defined essential foodstuffs (to support low-income Canadians in keeping at least the basics on their tables). Predictably, his proposal has been debunked by those who deny that corporate behaviour had anything to do with post-pandemic inflation.

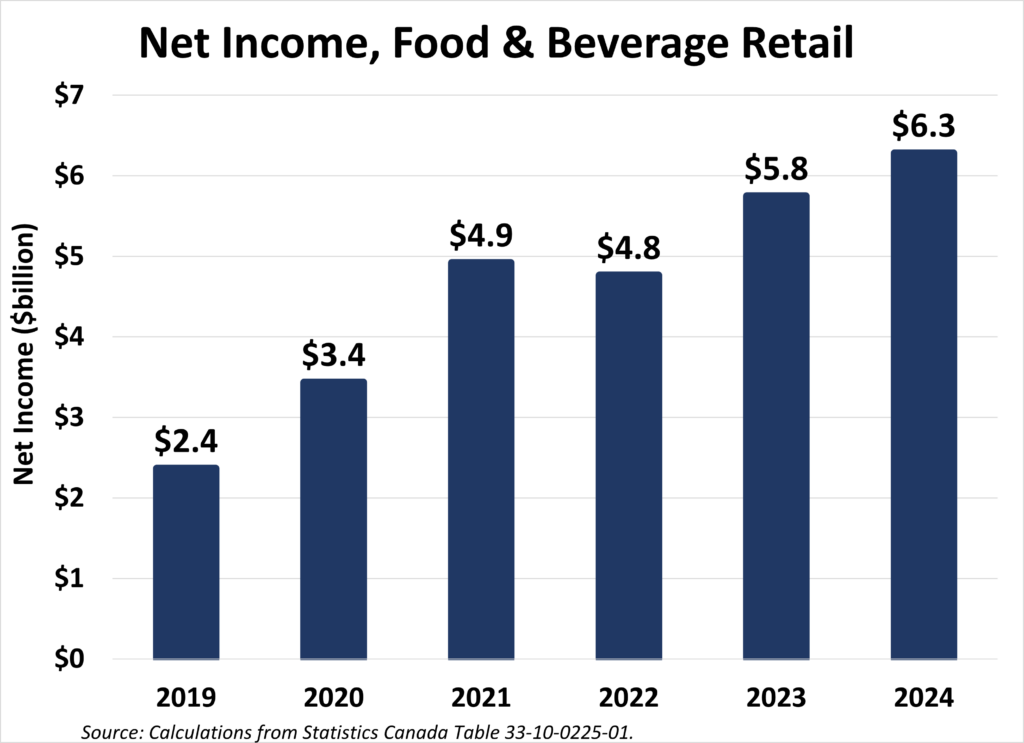

Let’s revisit the economic evidence about the role of profit-led inflation in the food price challenges facing Canada. Supermarkets were not just “passing on” higher costs for their inputs–they were substantially fattening their own take at the same time. After-tax net income in the food and beverage retail sector (two-thirds of which is captured by Loblaw, Metro, and Sobeys) more than doubled after 2019. In 2024 they reached an all-time high of $6.3 billion (compared to $2.4 billion in 2019, the last year before the pandemic).

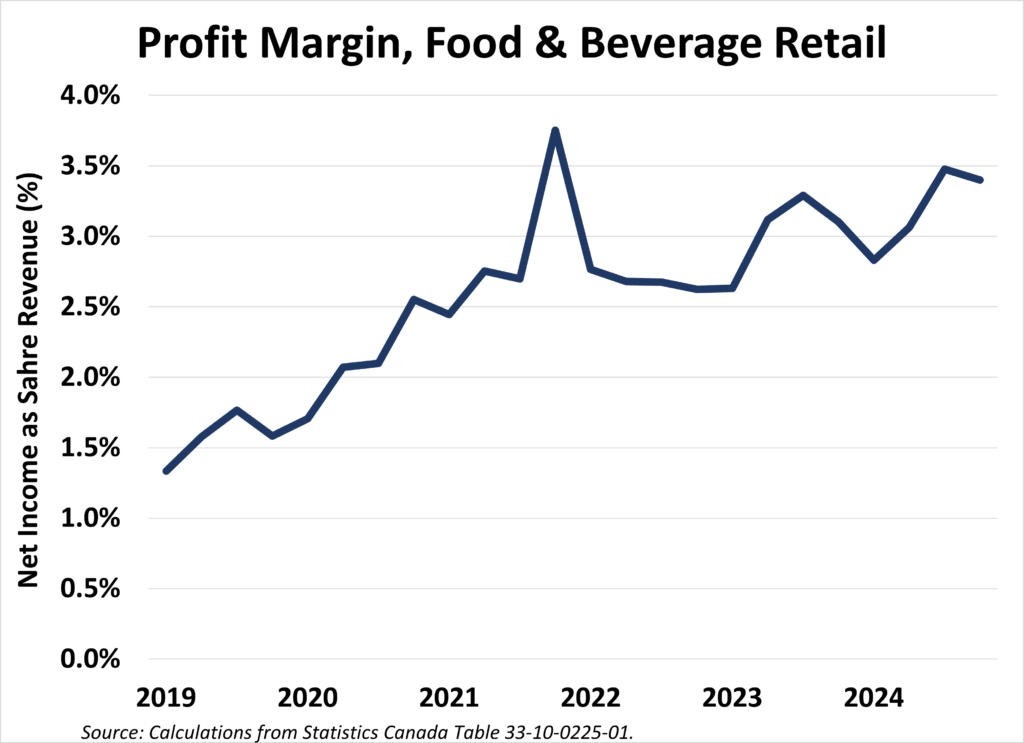

Supermarket CEOs and their apologists claim the growing mass of profits merely reflects the impact of growing nominal valuations, and that profit margins have not grown. This is false. As a share of total revenue, food and beverage net income has doubled, from around 1.5% of sales to over 3%. Some interpret this as evidence that food retail is a “low-margin” business, which is misleading. All the retailers do is buy food products from suppliers, put it on their shelves, and sell it. That’s why almost all retrial is “low-margin”, because the retailer doesn’t add that much value. But applied to a huge, stable flow of revenue (Canadians spend $200 billion on food every year), that “low margin” translates into enormous profits. Relative to invested capital (again, food retail is not a capital-intensive undertaking), this produces astronomical rates of return on equity: 25% or more.

An interesting (and infuriating) thing about food retail profits is that they have not moderated, even during the slowdown experienced by the broader economy during the painful disinflation since 2022. Overall corporate profits in Canada moderated during the period of high interest rates (in the face of slowing demand and rising unemployment). Profits in food and beverage retail profit have continued to grow. 2024 was the best year ever for aggregate profits ($6.3 billion) and average profit margin (3.2% of revenue). The decline in agricultural commodity and input prices experienced in the last two years has not been fully passed on to consumers, and hence food retail profits have continued to widen. This likely reflects both the high degree of corporate concentration in the sector, and the inelestic nature of consumer demand for food.

So both the continuing anger of Canadians at what they pay at the grocery store, and the NDP’s promise to do something about it, are ratified by this data on the continued excess profits of this concentrated sector. Of course, trying to address this problem is not straightforward. The idea of some targeted forms of price regulation has been proposed and applied successfully in other countries (see my review of Kamala Harris’s similar proposal, and the experience of several European countries that have implemented similar measures). Singh’s proposal is a reasonable and timely proposal to address a problem that is real–no matter how much free-market true-believers try to pretend it isn’t.