Halo Came Off Canadian Recovery as 2010 Drew to a Close

Canada’s recovery from the 2008-09 recession ground to a painful halt during the second half of 2010. The economy created no net new jobs from the summer onward, economic growth slowed to a crawl, and the nation’s current account deficit reached a record size. And all of that was while federal-provincial stimulus efforts (said to provide a boost equivalent to over 2 percent of GDP) were still in full swing. What will happen this year once deficit-obsessed finance ministers start to unwind those stimulus measures? Unless some components of private sector spending suddenly surge, a major reduction in public spending can only accelerate the evident slowdown, perhaps inducing another contraction.

Federal politicians, including Finance Minister Jim Flaherty and Prime Minister Stephen Harper, have stressed since the global financial crisis first erupted that Canada was somehow in a class of its own. That was the theme, of course, of Flaherty’s infamous November 2008 economic update which denied that Canada would even experience a recession (though we were already well into one). And this broken record has kept spinning. Canada is “the best place in the G7 to do business,” Flaherty boasted in October at the G20 summit Korea. No matter how tough things may be at home, the message is clear, things are worse elsewhere. So, Canadians, be thankful!

The claim that Canada survived the global downturn better than any other country was always suspect: there were several other major countries (including Australia, Norway, Brazil, China, even Germany) which suffered less damage to GDP and labour markets. But with the Canadian recovery hitting a brick wall mid-year, Canada has lost almost all bragging rights when it comes to international economic comparisons. In fact, by several key indicators, Canada was passed by almost every other G7 country as 2010 drew to a close. Consider the following indicators:

GDP Growth

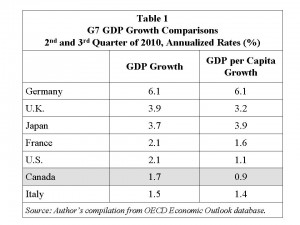

Canada’s GDP growth rebounded robustly in mid-2009, thanks to government stimulus efforts and a short-lived housing boom. Since spring 2010, however, growth has been almost non-existent. The Canadian economy grew at an annualized pace of just 1.7 percent in the second and third quarters – not even keeping up with economic capacity. (Remember, the economy must grow around 2.5 percent per year just to keep up with population and productivity growth.) The fourth quarter is shaping up no better.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Comparative data from the OECD indicate that Canadian growth during the second and third quarters of 2010 was the second-weakest of all the G7 economies. Growth was three times faster in Germany, and twice as fast in the U.K. and Japan. Moreover, even this comparison is skewed in Canada’s favour by virtue of the fact that Canada’s rate of population growth is the second-fastest (next to the U.S.) of any G7 economy. Therefore, Canadian growth needs to be faster than other countries, just to preserve equivalent levels of GDP per capita. After adjusting for population growth, Canada‘s per capita expansion (at an annualized 0.9 percent) was the slowest of any G7 economy during the second and third quarters of 2010 – worse even than Italy and the still-depressed U.S.

Jobs

For months Canadian officials have been boasting about the fact that Canadian employment has regained (since August) the peak pre-recession level it reached in late 2008. This means the recession is definitely over, right? Wrong! Of course, the level of total employment says nothing about the quality of employment: part-time and temporary work, and self-employment, have all grown during this time, while permanent fulltime employment is still lower than before the recession. But Canada’s faster rate of population growth also serves to make this indicator thoroughly misleading. With the working age population growing by 1.5 percent per year, Canada’s economy must create close to 300,000 new jobs per year, just to keep up. Regaining a two-year-old pre-recession employment peak still implies a devastating deterioration in labour market conditions.

Then, just as that watermark was gained in August, the job-creation process in Canada ground to a halt. Virtually no net jobs have been created since August. The unemployment rate has declined (reaching 7.6 percent by November), but that was due solely to a marked decline in labour force participation: with no meaningful prospect of finding work, hundreds of thousands of Canadians have stopped looking. In fact, the decline in the participation rate in November was the biggest one-month decline recorded by Statistics Canada in 15 years. While this trend is “convenient” in helping to reduce the official unemployment rate, it does nothing to restore Canadian production or opportunity – and thus is hardly anything to boast about.

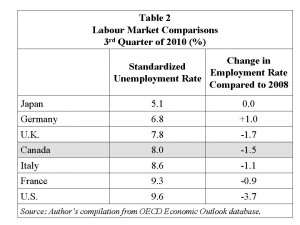

Our faster rate of population growth is one reason why Canada’s labour market does not look good by international comparisons, despite having regained its pre-recession employment levels. (In fact, several other countries – including Germany and France, where work-sharing and other pro-active efforts limited the number of people laid off during the recession, have also regained pre-recession employment levels.) By the OECD’s standardized measure, Canada’ unemployment rate in the third quarter was in the middle of the G7 pack, at 8 percent.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

And the decline in Canadian labour force participation means that comparing unemployment rates is increasingly misleading (since many non-employed individuals are not counted in the measurement of “official” unemployment rates). A better way to measure if a labour market has truly recovered is to compare the employment rate, which is the share of working age population actually employed (whether they are officially “participating” or not). This also incorporates the effect of Canada’s faster population growth. In November 2008, according to Statistics Canada seasonally adjusted data, Canada’s employment rate was 61.8 percent of the working age population. That is 2.1 points lower than the pre-recession peak reached in early 2008 – and only 0.4 points above the worst level incurred in mid-2009 in the depths of the recession. By that measure, less than one-fifth of the damage done to Canada’s labour market by the recession has been repaired. And the year-end employment rate is no higher than it was in April 2010, further reinforcing that Canada’s labour market rebound has been stopped dead in its tracks.

To make an international comparison (since consistent monthly data are unavailable), we will compare the employment rate in the third quarter of 2010 to the annual average for 2008 as a whole. In the third quarter of 2010, Canada’s employment rate was still 1.5 percentage points below pre-recession 2008 levels. Moreover, Canada’s ranking on this score is not good: 5th in the G7. Employment rates have fully recovered in Japan, and have actually exceeded pre-recession peaks in Germany (both of those countries have stagnant population). The U.S., of course, has experienced by far the largest hit to labour markets on this score, with the employment rate still almost 4 percentage points below its pre-recession peak.

Other Indicators

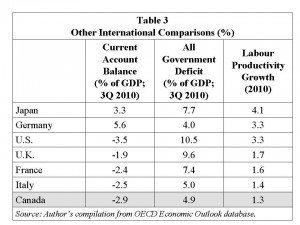

By other indicators, too, Canada’s relative economic performance is no longer worth boasting about (if, in fact, it ever was). Table 3 shows G7 rankings for three other measures of relative international performance. Much attention has been paid to Canada’s smaller government deficits; indeed, Table 3 indicates that Canada’s combined federal-provincial deficits, at just under 5 percent of GDP, were 2nd smallest in the G7 (bigger than Germany’s, and just slightly below Italy). The U.S. and U.K. had the largest deficits – about twice as large, relative to GDP, as Canada’s.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

However, there is another measure of a country’s accumulating debt according to which Canada performs badly. The current account deficit measures the rate at which a whole country (not just its government) is becoming indebted to international lenders. (It equals the difference between a country’s earnings in international markets, by virtue of exports, incoming tourism, and investment income receipts, and its payments to international markets.) Canada’s current account balance has slipped deeply into the red since the recession began – and that deficit (which, curiously, doesn’t get nearly as much attention as the government deficit) is getting worse, not better. The current account deficit reached an annualized $65 billion in the third quarter, by far the worst in Canada’s history. Relative to GDP, Canada’s current account balance is the second-worst in the G7 (behind only the perpetually deficit U.S.).

Not coincidentally, the G7 economies with large current account surpluses (Japan and Germany) are also the two countries which have fully regained pre-recession employment rates. This indicates, contrary to orthodox economic theory, that mercantilism works! Countries can “export” their unemployment problems elsewhere in the world, by generating and retaining large trade surpluses (so long as their trading partners tolerate the resulting deficits). Canada, in contrast, is going the other direction: our free-trade-obsessed officials promise to keep “playing by the rules” of international trade. And our monetary authorities allow the currency to soar unfettered (an outcome which is all the more puzzling as Canada’s trade performance deteriorates).

Finally, one of the most fundamental markers of a country’s longer-term success is its rate of productivity growth: the efficiency with which it converts human effort into the production of goods and services. Canada has been an OECD laggard on this score for many years, and the problem is not getting any better. Indeed, Canada’s productivity performance slipped further in the past decade (a problem which pre-dates the recession, and is closely related to our increasing national specialization in the production and export of non-renewable resources). Cumulative productivity growth in Canada sums precisely to zero since 2007.  (In other words, incredibly, Canadian labour productivity in the third quarter of 2010 was no higher than it was in the same quarter of 2007.) Even a modest boost in productivity this year will still leave Canada at the bottom of the G7 pack for 2010, according to the OECD – behind the Italians and the French, let alone the high-flying Japanese and Germans.

Conclusion

It is a myth to claim that Canada has outperformed other G7 economies during the global financial crisis, accompanying recession, and subsequent recovery. In fact, during the second half of 2010, Canada was clearly passed by the other leading industrialized economies according to most indicators.

It is also a myth to claim that the damage done to Canada’s labour market by the recession has now been repaired (since there are as many Canadians working as there were before the recession). After considering Canada’s relatively faster rate of population growth, less than one-fifth of the decline in the employment rate since 2008 has been recouped by subsequent job-creation. Worse yet, that job-creation virtually ground to a halt in the latter months of 2010, and there has been no improvement at all in the employment rate since April.

Yes, Canada’s financial system was more stable than in most other countries (mostly thanks to tighter banking regulations and a more risk-averse banking culture – structural features which predate the current federal government by many years). And our deficits are smaller than most (not all) other countries. But balancing the government’s books faster than others is a hollow claim to fame indeed, if it is coincident with (or, worse yet, actually contributes to) poor performance in the more fundamental measures of economic performance: employment, production, and productivity. On those scores, Canada’s performance has been lacklustre, and Canada’s international ranking is fading fast as the New Year arrives.

Great post. I think it is interesting to note that more than a few Bay Street economists who actually look at the data view the recovery through glasses which are far less rose tinted than those worn by the mainstream media.

Excellent post, and good point Andrew. I must say when I read some quite gleeful media analysis, (like today’s- nothing like that new year, new start to the economy positiveness)- I often have this vision of the character from 1984, Winston Smith, sitting at his crowded dismal desk with the retro looking media viewer, pulling news articles that require censoring.

However, I am probably giving the business news media too much credit here I am sure it is not as sophisticated.

I had an article in the CCPA Monitor that pretty much mirrors this post, however, I go into a few more scary looking social and economic measures.

The one to me is the manufacturing base. 600k net jobs since 2003 have disappeared into the optimistic winds.

My question is where does the recovery come from- given the integration of the Canada- US economy, a low dollar strategy similar to the mid 90’s may not have the punch it had back then, mainly due to the fact that the USA has been hollowed out of its manufacturing worse than Canada. (assuming we could real in the dollar that is, the oil/commodity dollar valuation process that we have got caught up on, is only pushing our dollar into the stratosphere).

So with the dollar rising further, and a further slowing of the US economy, and, as you mention the removal of stimulus happening, one does want to put on ones economic helmet, preparing for some kind of crash.

Of course it does not have to be this way, there is a way forward, but the politics is very far away, lost and stranded on some desert island.

Maybe somehow when the boat capsizes we will land on that shore. But I doubt it, history is not favourable to such outcomes.

It does make one want to write a song though. I am starting to think the art of economics needs some new tools and potentially a few new tunes away from the hymns of the current faith might bring about the new beat needed.

Something with a whole lot more foot tapping, for the worker is what I was thinking.

happy new year to all you musically inclined PEFers

oh and one final thought

I keep hearing we are heading for somekind of Japanese Stagnation.

Well, Japan did not have a hit to it’s manufacturing base the way Canada and the USA did. So I am not so sure if stagnation is such the lofty goal that the neo-cons seem to have faith in right now.

When the Bank of Canada decided to raise interest rates in three steps by 25 basis points each time, I wrote about how they had blown it. Subsequently David Rosenberg (who is also worried about deflation) credited the Bank with capping the housing bubble. Jim’s post makes the Bank decisions look more suspect. The interest rate gap has sucked in funds from abroad, pushing up the dollar. The capital account surplus is more than the mirror of the current account deficit, it drives it.

Given the personal debt levels overhanging the economy, there should be no expectation of increases in effective demand being driven by consumption. No consumption increase on the horizon, no business investment forthcoming.

So we have a sectoral boom in the tar sands, and our commercial banks doing acquisitions in the U.S. with their monopoly rents, and what else? Austerity government budgets driving more deflation I would think.

Yep and a simple rule change that put min down payments to 10-15% would have done the trick without the need to raise interest rates. But how do you get a majority if your government has just taken the piss out of the housing market? Much better to leave the top 40% alone and grind down the bottom 60.

I’m still waiting for 1930s or “Japan” price declines. Prices have not been stable either. I’m with Rosenburg, having the cost of owning housing growing exceedingly out of whak with incomes, is not a solution at all as assest inflation increase, an. I would stress Germany is embracing Austerity with the majority germans fearing Inflation, & over a third want the mark back, which I was pleasantly surprised to read, probably backlash for Merkels underwriting of Greece/Ireland. Australia, was amongst the first of G7 to consistently raise rates, which hasn’t crippled their economic recovery which was largely avoided.

Ignore Asset Inflation at your own economic peril. “The best example is the housing market, which concerns almost every individual household, where house prices have over the past decade consistently risen by or at least near a noticeable percentage increase, far above that of the consumer price index. This in turn, reduces, often substantially so, the disposable income of ‘ordinary’ households(average Joe), even in the absence of price inflation, but with the same outcome in the end” Inflation sucks for many, education, shelter etc.

@ Paul T My best guess is if were to see massive deflation, in the Coming Crash, we both know is coming; is to price it in terms of rising currencies, in agriculture commodities such as sugar, cotton; or industrial commodities like copper, or even priced in gold or silver

Will we see deflation, in terms of US dollars probably not, as we have not since ’08 when default was a possibility.

The neighbors south have borrowed to an extent, that in my opinion cannot ever be paid back without default where US bondholders take a loss of valued money, or mass inflation to lower the real US debt burdern to not take a loss of valueless which just gets worse; we have Republicans who will fillibuster any tax increase, & compromise on government spending. Then just as bad, from the democrats, fillibuster any spending cuts while compromising on taxes.

Creating the worst outcome, high spending, and low taxes like that characterized the George W Bush administration (Is Afgan still Bushes war?). You an inflationist yet?

Private sector debt is also critically important here in this story. The level of leverage in the financial sector is at scary proportions. Equally scary is the relative carelessness of policymakers to this problem. While there is a lot of talk and fear in Ottawa these days about the ‘debt problem’, the sheer pigheadedness arises when we read the finer print of a lot of these policy discussions.

The prime ministers comments last month warning Canadians to be cautious but stating that there is little government can do to stop them from overextending themselves. Translation: we will focus our policy efforts on austerity, and while consumers may be over-leveraged market forces will bring it back to equilibrium.